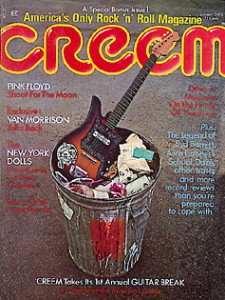

Van Morrison – Creem

Van Morrison Talks Back

The bardic-maned bottle-cruncher from Belfast calls the shots in a fusillade of timely rants against the record industry, concert scenes, and other deserving targets. brittle spittle by Cameron Crowe.

“My first impression of Van Morrison,” Jimmy Page recalled of his days as a session lead-guitarist for Them, “was that he was a terrific singer.” Page paused for a short time to consider his statement. “No, I take that back. I thought he was a really dirty singer. Everything he did had a real big pair of balls to it.”

Despite the fact that his post-Them solo career has been relatively low-keyed, Van Morrison has recently taken to performing “Gloria” onstage again. Wisely, he saves it for next-to-last, though no one who has witnessed Van Morrison live in the past half-decade would’ve dared hope for this. Swaying stiffly while the ten-piece Caledonia Soul Orchestra surges through the all-time ball-buster classic, he cracks a slight smile that soon becomes a broad grin. For once, and in what used to be the rarest of moments, Van Morrison and his audience make contact.

But it’s happening more frequently these days. The old uncommunicativeness, the quirky and erratic performances are vanishing, along with the almost cult-like audience relationship. What’s more, Van can feel the change and is drawing unprecedented strength from it, to the delight of his massive following.

Nonetheless, Van still has extramusical problems to resolve. An extremely guarded man personally, he has suffered the weight of a press that has, perhaps out of spite over his insistence on privacy, chosen to stress the idiosyncratic nature of his past performances and depict him as an on-again, off-again rock ‘n’ roll performer.

Although Van Morrison is not noted for his overwhelming generosity in granting interviews, he chose to discuss his current state of affairs with Creem on the eve of two highly successful sold-out shows at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium and a new LP Hard Nose the Highway. It was his first conversation with an interviewer in over a year, and may well be his last in this country for some time. Van spoke slowly and sometimes dramatically… always careful to choose his words well.

– C.C.

***

How do you feel the present stage show compares to those you’ve had in the past?

Well, that question is really a good one to ask me. The stage show has always been and always will be good when the music’s together. Right now, the music is together and the live shows have been going great. But that whole thing about my inconsistency on stage, what happened was that I did a couple of shows last year that just got blown up out of proportion. I did a show at Winterland and some other place, I forget, that they just took and blew up.

They? You mean the press blew it up?

Yeah. Then after those shows, all this stuff started to go around about my performances. You see, the press picks up and publicizes all the negative things. Any negative thing they can come up with, well, that’s what they pick up on. The press never picks up on the positive.

You’re not on every night. You can’t be on every night. But I can honestly say that with this group of people, it’s mostly on. But the whole thing… I’ve had people even from my own record company hassling me about this question. Just because of a couple of shows. The press get hold of something like that and instead of just taking it for what it is…they want to make a big deal out of it.

So, in actuality, what was the show at Winterland?

What was it? It was just a show where the hall . . . Well, the hall is an ice rink and they have it crammed full of people who don’t come to hear music. I don’t know what they come for. It’s slightly better now, but it was just very uncomfortable, so I didn’t dig it. The show wasn’t good. Maybe I’ll get even deeper into it . . . Bill Graham. If everything’s going groovy, then Bill Graham is your friend. But if things aren’t going groovy man, he’s just not around. You don’t see him. I’d just like to say that because I think it needs to be said. They love you when you’re up, man. Everybody’s your friend when it’s happening. Whether you’re a plumber or an electrician or you wash cars, it’s the same thing. It’s no different with performing or anything else. You’re not a robot, you don’t do it the same every time. The kind of thing we’re doing on stage now, a lot of it is spontaneity.

What I’m trying to say is that it’s not a rock ‘n’ roll stage show, and it never was. I’ve made rock ‘n’ roll records, but then again I’ve also made jazz records, I’ve made country-and-western records. I just think that what people expect is not what they should expect from what I do. They expect something that they’re not gonna get because it’s just not there. I’m not a rock ‘n’ roll performer. I prefer, like I’ve always said, to play smaller halls. Unfortunately, I have to support a lot of people and you don’t make any money playing small halls. You barely make any money playing big halls by the time you pay expenses. So that’s the game you’re involved in. The people who are in this business, like so-called promoters and what have you. They tend to lock you in. They have these regimental-type halls, the way they run the place is regimental.

And they’re geared to attract the same audiences to every show . . .

Oh yeah. It’s just the same people over and over again. You’re supposed to be this stereotype. You know what they can do as far as I’m concerned? They can shove it. Also, they have to take their chances. You take your chance when you buy a ticket. I’ve paid a lot of money to see big artists that I dig and I’ve run up big bills seeing people. And I’ve been disappointed. But that didn’t stop me from digging them. When you’re in this field, you know that everybody can’t be on all the time. That’s if you’re an artist. Now if you’re an entertainer, it’s a different trip. That’s why most rock ‘n’ roll people are mainly entertainers. The music is a secondary thing.

The last time I went to see a rock group, a really well known rock group too . . . they’re supposed to be the biggest rock ‘ n roll group in the world or some jive like that, the music may as well not have been there. Their whole trip was visual. Totally visual, and the audience was coming to see this stereo-type that they read about in all these magazines. It was just a big disappointment. Any musician that I met who went to see the show . . . then again, I only saw one show. Maybe their other shows were better, but most musicians who went to see that show say that the music wasn’t even in the running. So there you’ve got people coming to see an image. They’re coming to see this image that they read about in Rolling Stone or whatever. I mean, what does it have to do with music?

Also, what does a person’s personal life have to do with music? That’s what they thrive on. I think that’s the main reason why there isn’t enough musical education happening. For instance, kids don’t know . . . they hear a song maybe fifth-hand or something like that of a group doing it. And if they only knew that the original was ten times better. But they didn’t know about that. All they know about is what they’re programmed to hear. It’s all one big program from the publicity and the press and what they see. It’s all one big program and they don’t really have much choice. There have been a few good articles written about me, maybe a dozen that I’ve read that were talking what we were saying. Most of it is pointless. That’s why I never do interviews anymore. It’s all pointless. Take for instance my relationship with my record company. The guys that work for the record company can’t relate to me. But they can relate to somebody like . . . how can I put it? They can relate to somebody . . .

Who fits the mold?

Right. Took the words right out of my mouth. I don’t fit the mold. It’s not that they can’t totally relate to me. They can relate to me when they want to. And they know that I can relate to them when I want to. There’s just a lot of unnecessary stuff that goes down about what is what. I do my gig, which is making albums . . . then the other gig is to sell them. I think the truest part of what I do is making records. I make the record, I give it to the record company and it’s in the grooves. You know what I mean? No matter what anybody writes, no what ego trips people are on . . . the music is there. It won’t change and people who buy records buy them because they dig them. If they don’t dig them, they throw them away. Or they don’t buy them in the first place. You can’t shuck the people who buy records . . . unless they buy them because they’re programmed, which is what’s happening a lot these days. If Joe Blow is in this year, then all of a sudden everybody’s buying Joe Blow records for two years. Then you don’t hear from Joe Blow for another two years . . . then it’s somebody else. That seems to be the pattern. What I’m trying to say basically is that you have to keep out of that whole scene to keep from becoming a temporary thing.

How does Hard Nose The Highway fit into the scheme of things?

It doesn’t really fit in to anything. It’s an album. It’s now how I live. You know what I mean? When I make the music, that’s where that’s at. And when it comes out on a record, that’s the record of the music I was doing at the time. But when I’m doing something else, I’m doing something else. A record doesn’t detail a person’s changes. If I make a record, that’s it. It doesn’t affect how I live and isn’t how I live. It doesn’t affect my life and my life doesn’t affect it. What can you say on forty minutes of wax! Twenty minutes a side. I mean I couldn’t possibly explain all your changes on that. A record is like a very small part of my changes . . . of what I do. If I could put out a triple-album without being hassled about it, I would put it out. It would be a lot more of an honest representation. I could easily make a triple-album of the music that I wanted to put out, but there’s so much involved. That’s the way the business is set up. It’s just hard to . . . it’s hard to make music for a living.

Do you feel that the next album you’re growing towards any particular musical direction . . . or growing away from any direction?

Well, I think it’s a change from other albums. I’m definitely writing different songs. I’m not writing any fairy-tale songs any more . . . not on this album. It’s just another type of song that I’m writing these days. A little more down to earth.

Do you feel that there was a connection between Moondance, His Band and the Street Choir and Tupelo Honey?

A connection. How do you mean that?

Well, it seems that one could play all three of those albums one right after another and not feel jolted into any other particular direction.

You’re probably right.

And Saint Dominic’s Preview seemed to be a lot looser.

Yeah, you’re right. It was a lot looser, but then again, you’re talking about albums and stuff like that. If you want to talk about those three albums or four albums or whatever, that’s just what got out on the records. You don’t see what’s in the can. Or you don’t see what else is written. That’s what I’m talking about. When you make an album, you’re very limited. You can only get so many songs on a single album. At the time I did those albums, I’ve got stuff in the can that’s got nothing to do with the mood of those particular albums but I did the songs at the same time. The thing about it is that it didn’t fit on that particular album, so it went in the can. What I’m trying to say is that when I’m doing an album, I’m just not doing an album. I may be doing four albums. You know what I’m saying? I record a lot of stuff and I have a lot of stuff in the can. So an album is just part of what I was doing at the time. There’s no direction. I haven’t got any direction. I mean, I’ve got stuff in the can from The Street Choir album that was totally uncommercial. I’ve still got it in the can because it’s not acceptable unless you look at it as jazz. And people don’t look at my music like that. You know what I mean? It’s like, there’s all kinds of directions happening in the music. But when it comes time for an album, you have to limit it to one direction. I had another album that I was gonna put out then that was a totally different direction, but it wouldn’t have made sense.

This is after The Street Choir album?

Well, for that matter, before. When I was doing the Moondance album, I had stuff that didn’t come out because it didn’t fit on that album. When I was doing The Street Choir album there was a lot of tunes left over. When I was doing Astral Weeks there was stuff that wouldn’t fit on that album. Before that I had stuff. I don’t think an album is a direction. As far as musical growth goes it’s not. I can’t see any particular direction. I think I’m doing basically what I’ve been doing . . . it’s still basically the same thing. That’s how I see it.

Are you satisfied with that direction?

Well, you’re never satisfied. I’m never satisfied with what I do. It’s my job. It’s my job to make music, and I’m not satisfied. It’s just what my job happens to be. How many people do you know who are happy with their jobs? Sometimes I do something and get satisfaction from it, but it’s very rare.

Do you still feel the same things that led you to write “Domino”?

How do you mean?

I guess it kind of ties in with your retirement . . .

Well, that retirement thing was the phoniest thing that ever happened. I never retired. I was still working. I was working in clubs. A certain writer thought up this thing about my “retirement”. I’m always playing. I haven’t taken a holiday in a long time. I don’t go very long before I’m playing somewhere. It may not be in every paper in the country where I’m playing or it’s not reviewed by every reviewer. But I’m still playing. It’s just their game. These journalist are writing about their game. And it doesn’t have anything to do with the cat that’s living the life.

That brings us back to “Domino”. Do you feel that the thoughts you just expressed were the same ones that led you write “Domino”?

You mean “time for change” and all that?

I mean the overall “lemme alone” theme of it.

Yeah right. “Don’t want to discuss it”. It can’t really all be in one song, though. You can’t really say what you have to say in one song . . . or one album. Maybe you can never really say what you want to say. It’s that difficult. Who knows?

But you made an attempt with that song.

Not really. I don’t think I made an attempt to say it with that song because it never really got very deep. It never really said it. I didn’t spend much time working on that song . . . to say what I wanted to say. It said some of it, but not really everything. But see, they used that song in this article about my retirement, or my so-called retirement, that I was retiring and should tell everyone to listen to the lyrics of “Domino.” I mean that’s probably something I said off the top of my head. You know what I mean? For instance, if you’re doing something and you don’t feel particularly right about what they’re doing at the time. Or the situation. They don’t want the situation or whatever. That person is liable to say twenty different things. The person is probably under a lot of pressure. The thing about me saying “listen to ‘Domino'” to all these journalists. I mean, I probably said that because somebody stepped on my toes or something. I was too ridiculous to get immortalized.

Then what was the actual story behind the Jackie DeShannon team-up?

There was no story, there was no team-up, there was no nothing. It was just musicians getting together to play. I mean if I said that I was gonna play with an unknown country and western band in Oakland, you think they’d write that up? It wouldn’t be worth anything to write that up. If I was playing with an r & b band in Oakland, or if I was jamming with some of my friends who don’t have big names . . . they wouldn’t write that up. They don’t have a name. They’re not a product. If you don’t have a name, you’re not a product . . . so you don’t get written up. If I said I was gonna go down to some bar in San Jose and jam with the piano player, who would want to write that up? Who would want to read that? It doesn’t sell. What sells is bullshit. That’s what sells. That’s why you’ve got the magazines. That’s why you’ve got the names. That’s why you’ve got the whole business. It’s down to names. Who you know and what sells. It’s all business, it’s all politics. It has absolutely nothing to do with art . . . or music. If I changed my name, called up a guy in a club over on the East Bay and asked him for a gig . . . who would write that up? They’ll only write it up if it’s Van Morrison playing there. If I changed my name and played with a totally unknown band, it wouldn’t be news. But I would still be doing it.

Have you contemplated doing any of these things?

No, I haven’t contemplated doing any of these things. I’m just giving you examples of what I’m talking about. I would still be the same person doing the same thing I do. It would be exactly the same, the only difference is that it wouldn’t be a name. It’s like Disneyland. That’s a name. Beatles is a name. Bob Dylan’s a name. Heinz Beans is a name. Arrid Extra Dry is a name. You see what I’m trying to get at? See what I’m trying to say?

Do you feel you’ll ever get back towards rock ‘n’ roll again?

No. I don’t know why they keep writing me up as a rock ‘n’ roller. I was never in rock ‘n’ roll. I’m a singer. And I’m a musician. I’m in music, not rock ‘n’ roll. They keep putting labels on you all the time.

Is that why you were upset with the Them re-release? Was it the liner notes?

The liner notes were okay. The liner notes on the original Them albums were jokes too, they were a standing joke at the time they were done. But that’s just the system. They want to put something funny on an album jacket. At the time we didn’t even see it when it was pressed.

Why were you upset with the Them re-release then?

The answer to that is very simple. I still haven’t seen the royalties from all those Them songs yet.

You seem upset that you haven’t been portrayed in the proper light by the media. How would you prefer to be presented?

Well, I’d prefer to remain anonymous but that’s not the way it is. You see it’s not important who’s playing it . . . you’re only a vehicle for what you’re doing. You’re a vehicle for music to come through. The fact that you have a name doesn’t mean anything unless that’s what you’re into. If you’re into having a name, then that’s what you’re into. You don’t know who the tympani player with a certain symphony orchestra is. You may not know who the tympani player is but he may have good chops. He may just blow your mind. He may not be on the cover of Rolling Stone but it’s not that important because he’s playing music that you dig. And you’ll still dig it even if you don’t know any names. If it just says The London Philharmonic and there’s no other names on the record . . if you dig the record, you’ll dig it. What do you need to have a name for? The name is just a product. A musician’s name is not important at all. What it’s all about is that you’re playing music for people to listen to. To give those people something. It’s a process of giving people happiness, sadness . . . whatever, out of the music. The names are secondary. I don’t like to be portrayed at all. Just say that I’m a musician and leave it at that. But thanks to this business, if I did that I wouldn’t make a living.

Outside of what you said earlier about albums, have you been content with your albums?

Well, I’ve been satisfied with a lot of Astral Weeks. I’ve been satisfied with the other things to a degree, but I’ve never really been satisfied. When an album with my name on it comes out, I get the album and play it a couple of times. After that . . . I don’t play it. I don’t listen to my own music. I’m too busy working on something else.

Have you ever thought about giving up recording and concentrating exclusively on the live shows?

I’ve never thought about it. No, not really. I think recording is a good medium in itself. It’s a good way to give people what you have to give them. If it’s a really good record, then people can play it for a really long time.

What do you feel has been the quality in Astral Weeks that has made it last so long?

I couldn’t say. I don’t know. It was just what was happening then . . . I don’t know.

You have said in other interviews that Astral Weeks was a major step for you in that you finally presented yourself in a light that you had wanted to present yourself in for a long time.

That’s true. I wanted to make that record for a long time. But there’s many other things that will never go on my records that are even better than that. I sing my best when I’m sitting around with a couple of friends. But that’ll never be on a record. You can’t catch that. You can’t be in a recording studio all the time. So it’s really hard.

Are you comfortable in the studio?

Yeah, mostly I am. But you know what I’m trying to say? You can’t catch something when it’s just happening. It’s like a painting or something, except the painting’s still there . . . it remains. It’s hard to get the music to a stage where it’s great because of all the pressure. The pressure of the way the whole business is set up. It makes it hard to get a flow going. . . in your work. It’s hard to get comfortable and put out your best stuff. It’s just like a regular job. Although people who have regular jobs may think that doing what I’m doing is really a gas . . . they’ve got another thing coming. It’s not. It’s just as hard as their gig and it’s probably even harder.

Courtesy of Creem – Cameron Crowe – October, 1973