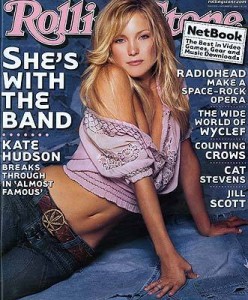

Rolling Stone #851: Almost Famous

Romancing the Stone

A final word from the man behind the boy

The year was 1973, and I’d just walked through the San Francisco offices of Rolling Stone magazine for the first time. Before this I had been a voice on the telephone, a freelance journalist dealing with music editor Ben Fong-Torres. Now Fong-Torres was taking me to the office of the magazine’s founder and publisher, Jann Wenner. (The hand that shook John Lennon’s hand, I remember thinking, is now shaking my hand.) Annie Leibovitz’s original photos lined the walls. All around me were the real-life versions of names I studied in the magazine’s hallowed pages. I was sixteen, with an orange bag strapped to my shoulder, and I felt every eye in the place on me. It felt like a scene from a movie. Twenty-seven years later, it was.

Standing on the Los Angeles set of Almost Famous, in a room outfitted to look exactly like the old Rolling Stone offices of ’73, I quietly took in a big whiff of my past. Standing nearby was a sixteen-year-old unknown actor from Utah named Patrick Fugit. My orange bag was strapped across his shoulder. I watched him walk the hallway, every eye on him, moving into an office where he would meet actor Eion Bailey, as Jann Wenner. We were halfway through filming, and it was just one of the daily time-trippingly emotional moments that came with making a movie based partially – OK, totally – on my life. Personal movies, just like personally based records, have always been my favorites. Albums like Joni Mitchell’s Blue or movies like Francois Truffaut’s The Four Hundred Blows and Barry Levinson’s Diner are timeless. They make it look easy. But the hardest part – and I say this with a note of caution to any future inward-looking directors – is casting yourself.

It is January of 1999, and it’s there in the little ways people are looking at me. The gentle manner with which friends and loved ones place a lingering hand on my shoulder and ask, “How you doing?” It’s there in the extra looks of concern all around me.

They think I’m going crazy.

How I’d gotten to this point, I wasn’t sure. After the surprise success of Jerry Maguire, I’d had a couple decent script ideas. One was a homage to my favorite TV show, Hawaii Five-O. I’d been writing a psychedelic Jane’s Addiction-filled thriller set on Kauai. It sounded good in my head. On paper . . . hmmmmmm. I hit a rough stretch and went flying back into the arms of an idea I’d been returning to for years. It was a warm blanket of a script. I’d been circling it for a long time. It was an autobiographical movie set in 1973, featuring the music I’d loved and a host of vivid characters I’d met as a fifteen-year-old journalist. The problem had always been the character at the center of the script. The one based on me. Again and again, I’d left the “me” character to fill in later. I even gave him a colorless name that screamed, Better name to come – William Miller. I mean, come on. I can barely listen to my own voice on the answering machine.

Then, in a burst of creativity, it started to fall together. The key had been to get more personal with it, rather than less. I began to write about my own family in fairly raw terms. How my schoolteacher mother had banned rock from our house, how my sister had heroically smuggled it in and how rock changed my life . . . and changed our family. Before I knew it, I had an untitled, 172-page script. I showed it to Walter Parkes and Laurie MacDonald, the heads of production at DreamWorks films, who liked it immediately and in turn showed it to Steven Spielberg. Half expecting them all to consider it more a novel than a film, I had returned to the warm creative waters of the Hawaiian thriller. I was visiting Walter and Laurie one evening when Walter handed me the phone. “It’s Steven,” he said.

“I read your script,” said Steven Spielberg. “Shoot every word.”

And so began the journey of actually making Almost Famous. I began casting each part meticulously, seeing tens upon tens of hopeful actors and working on every tiny character in the script . . . except the one based on me. Gail Levin, our peerless and soon-to-be-sleepless casting director, had put feelers out all across America and England. I delayed diving into the videotapes that were starting to flood our office. “I’ll get into it next week,” I’d say, every week. Somehow, next month always seemed like the best month to begin meeting . . . me.

The months clicked by as I carefully cast parts like New York Bellman, Fan #1, Long-Haired Guy in the Lobby and other seemingly crucial parts. Increasingly, Gail would slip in a young actor to play William Miller. The process was always otherworldly. A young, pale, long-faced actor would shuffle in and face me, the older, pale, long-faced version of himself, and we would look at each other, making uncomfortable small talk.

“So, do you like music?” I’d ask, thinking, This is strange.

“Sure,” the actor would say, thinking, This is weird. We’d read the scenes for a bit, and then later I’d invariably tell Gail, “Let’s keep looking.”

“What are you looking for?” she’d ask.

“It’s not quite right,” I’d say. “Now – about the part of the Third Groupie . . .”

We were in New York for further casting when a call came in from Walter Parkes and Laurie MacDonald. We chatted cheerfully about how well everything was going with the smaller parts.

“Great,” said Walter. “But do you have the kid? Because the kid is in every scene.”

“I’m still looking.”

“We’re running out of time,” Walter implored. A cheap shrink could have figured this one out long before. Very elegantly, in the way only we can delude ourselves, I still believed it was a movie about rock, family, groupies, musicians and music . . . everything but the elephant in the room. “You gotta cast yourself,” said Parkes. “Because the kid is the movie.”

Late at night, Gail had been poring over the hundreds of hours of audition tapes. We knew we wanted a fresh face, someone who would personify pure fandom and the look of a kid who’d run away and joined the rock & roll circus. Our models were Louis Malle’s protagonist in the incredible Murmur of the Heart, and, of course, the granddaddy of all cinema doppelgangers, Jean-Pierre Leaud, the star of Francois Truffaut’s autobiographical films. But finding a young discovery who can carry an entire movie is the holy grail of casting. Most filmmakers who conduct nationwide searches invariably give up and go with a proven commodity, someone with credentials. As the pressure ratcheted up, I began to watch more and more audition tapes with Gail. English boys. City boys. Southern boys. A fourteen-year-old from Idaho sent a tape of himself playing Nirvana’s “Lithium” on guitar, followed by a brilliant monologue on why music matters. (We later hired him for the Topeka party scene.) All of them trying hard to hit a bull’s-eye, and I hadn’t even hung up a target.

That’s when the gentle hands started resting on my shoulder. That’s when I started to realize the train was thundering down the track. I was a long way from the comfort of that Hawaiian thriller. Holy shit. I was making a movie about me.

There was a tape, though. A tape from Utah that Gail had been impressed with, watching on one of those late nights in New York City. Only one problem. Somehow, in the packaging and transporting of umpteen boxes back from Los Angeles, the tape had vanished. Frantic calls went out to the New York hotel, the airfreight company that had shipped the tapes, the production assistants who’d boxed them. The now-mythical Utah tape was nowhere to be found. Finally, after searching every box from a now double-nationwide search, the tape appeared, misfiled in a stack of rejects about to be destroyed. On a Sunday morning in February, we watched the audition of a kid named Patrick Fugit.

He was a pure soul, an authentic Utah kid with a bowl cut and a funny put-upon manner. He waved his arms around a lot. He made us laugh. A day and a half later, he stood in my office. His parents, Bruce and Jan, waited patiently downstairs. It was Patrick’s first visit to Los Angeles, and he was very cool about it. But his saucerlike eyes gave him away. He took in every photo, every shred of everything in sight. He was a skateboarder but not a rock fan, not yet. He was a beginning drama student. He’d done two tiny walk-on parts for Touched by an Angel, the TV show that filmed near his hometown of Salt Lake City. He was sixteen. His favorite movie was Forrest Gump. Even his name was utterly real. Fugit. I could only imagine the nicknames he’d endured.

We spent an hour reading scenes and videotaping his performance. I shouted directions from behind the camera, in the middle of acting. He rolled with it. “More angry,” I’d say. He got angrier. And then, doing a scene where the guitarist Russell Hammond (Billy Crudup) is trying to convince William to come along to Cleveland for one more show, Fugit hit a stunning note. “I want to go home!” And he repeated it again, loudly, into the camera, emphasizing the words in sign language. He was not me. He didn’t look or act like me. But world around him, reminded me of something more important – how it felt freed from the “me” of it all. He was the character, that boy at the circus, William Miller.

We gave ourselves a grace period. Patrick returned to Salt Lake, and I watched the tape a hundred times or more. I played Led Zeppelin and Neil Young tracks along with his audition. His face soaked up music. There was no mistaking it. This was our guy. In-experienced and untrained as he was, he was joyously and unashamedly real. But there was one moment on the tape I kept returning to. It was Patrick’s simple wave goodbye. His wave said more than my script. It was a young man’s goodbye to the past, a split second before the future would change him forever. It’s captured in the finished movie, too, when William Miller bids farewell to Russell Hammond in the hallway of the Topeka airport. To me, that wave was Pet Sounds, all in a gesture. I won Fugit the part.

“I’ll call him tomorrow and give him the job,” I said.

“No,” said Gail, with the power of Zeus. “Call him now!”

I picked up the phone and called Patrick Fugit in Utah. The experience to come was deliriously fun and certainly tough. I learned more than ever about the privilege of being given a huge canvas on which to paint a film, a love letter to music. I did many takes. Shoot every word. I shot scenes from many angles. Shoot every word. I worked on every detail, large and small. Shoot every word. The great cinematographer John Toll, our producers, my wife, editor Joe Hutshing and the actors showed the patience of Job. Shoot every word. I didn’t quite shoot every word, we came close. And rock would invade Patrick’s soul, too. The kid who once thought Led Zeppelin was “a singer” now craves Physical Graffiti. But this was all an unknown future as I sat waiting for Patrick to come to the phone.

“Hello,” he said. His young, unchanged voice reminded me of someone I used to know.

“Patrick,” I said. It’s Cameron. Do you want to come make a movie with us?”

I could hear him breathing on the other end of the line. Both our lives were about to change. “Wow,” he said. “I’d love to come make a movie with you.”

And onward we went. Fugit’s performance in Almost Famous is his own creation, beyond all I’d imagined. In the course of the movie, Fugit’s voice changes…he joins the circus…he gets tired…he rallies…he grows up a little, just like William Miller. And several months into filming, on a New York street where Jann Wenner had come to make a cameo appearance, I introduced the two. It had all come full circle.

“He’s better looking than you were,” cracked Wenner.

“Well, he’s not exactly me,” I said.

“Thank God.”

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #851 – Cameron Crowe – September 22, 2000