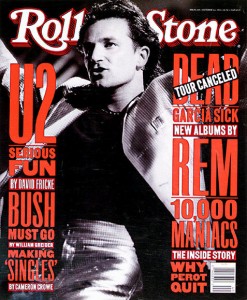

Rolling Stone #640: Singles

Making the Scene

A Filmmakers Diary

“Andy’s dead,” the voice said flatly. It sounded so unlike my old friend Kelly. This dispassionate monotone on the answering machine. Kelly was one of the most excitable guys I knew. In recent years he’d become a rock manager, guiding the career of a fledgling Seattle band named Mother Love Bone. Its lead singer and frontman, Andy Wood, had been successfully battling a nagging heroin problem. But the night before Wood was to meet his boyhood idols Paul Stanley and Gene Simmons of Kiss, he’d scored some deadly heroin on the street. They found him comatose in his apartment, his favorite T-shirt mysteriously ripped to pieces in the washer. After several days on a life-support machine, Andy Wood slipped away. “I’m still at the hospital,” Kelly said with a sad sigh. “I’ll be at home later.”

My wife and I stared at the answering machine. Within a few minutes, we’d psychoanalyzed Kelly’s voice. He was in trouble. No, worse, he was a ticking time bomb. He needed help. He needed friendship. We got in the car and drove to his house – immediately.

Rounding the corner to Kelly’s place, it was obvious that his other friends had the same idea. Cars lined the streets. Inside the small house were Andy Wood’s friends, his band mates, members of other bands from throughout the city. The same odd look on all their faces – I’ve never had a close friend die before. And still they kept arriving, these dazed Seattle musicians – a breed all their own, the inspired children of pro basketball and Cheap Trick and Led Zeppelin and Black Flag and Kiss.

I was thirty-two at the time and felt a part of something. Somewhere around midnight, warming over a barbecue pit, I felt rocked by the whole experience. I’d been working pretty steadily since I was fifteen, and looking back, most of my friends were made through work. They were acquaintances more than friends. And here were these disconnected single people, many from broken homes, many meeting each other for the first time, forming their own family. In the coming years, many of the musicians in that room would see success far beyond their early dreams, beyond even the arena dreams of Andy Wood. But that night it was mostly about staying warm, pulling together. It was almost instinctual. And I thought about Los Angeles, where musicians would already have slipped audition tapes into Kelly’s pocket.

I was in the process of rewriting an old script of mine at the time. It was called Singles, and that night it took a different course. I wanted to write something that captured the feeling in that room. Not Andy’s story but the story of how people instinctively need to be together. Is anybody truly single? I knew I’d soon be rewriting the rewrite of my script, and I knew I had to direct it, too.

Three years later, Singles is a movie in the can. It’s the story of six Seattle urbanites, their lives in and around the apartment complex where they reside. A lot of the music was provided by musicians and bands, but contrary to some advance reports, it’s not a movie about the birth of the now-hot Seattle scene or even the story of how Mother Love Bone gained a new singer (Eddie Vedder) and became Pearl Jam. It’s the story of disconnected single people making their way, forming their own unspoken family. Everything about the movie screamed obsession. Making it in Seattle became an obsession. Getting it perfect became an obsession. And early on, I started obsessively keeping a journal.

Looking at the stacks of pages of diaries, I feel like the guy on The Outer Limits who revisits the home he lived in 300 years earlier. Printed journals often have a self-serving sheen over them. Like bad date talk, they’re often a laundered version of reality. I wanted this to be different. Some of my earliest reading pleasures were Pete Townshend’s 1970-71 essays in ROLLING STONE about his work with the Who. His writing gave me the feeling that he was sending a letter to a friend, and in that spirit, I wanted to keep a running account of Singles.

Some nights making the movie, I’d write for an hour, other times only a few minutes. (One entry reads only: “Aaaaaaaaagh!”) These raw, nocturnal entries were more like a cleansing ritual that a guide to intelligent filmmaking. To anyone offended, please know that I intend to offend myself as well. So for whatever reasons, perhaps in the spirit of preventing you at home from developing a need to write and direct a collagelike movie with eighty-seven speaking parts, I present this to you now.

10-15-90: Campbell Scott will play the part of Steve Dunne, the traffic engineer at the center of Singles. Everything is exploding at once for Campbell. Today he got the part opposite Julia Roberts in Dying Young. He’s playing a leukemia victim who falls in love with his nurse. A problem surfaces – in Dying Young he loses his hair. Many nervous calls are traded between our movie and Dying Young. Toward the end of the day, it’s resolved. Dying Young will not actually cut his hair; he’ll wear a bald cap with a wig over it. Whew.

2-24-91: Campbell has arrived in Seattle. We meet for dinner. His hair is very, very short. He is pale. He looks like a leukemia victim. Sitting in a dark restaurant, my early fears slip away. We’ll do something about his hair. Campbell is psyched to play the part of Steve. We’re in sync. I raise a toast. “Don’t jinx it,” he says.

2-25-91: First day of rehearsal goes smoothly. We blast through the scenes. Kyra Sedgwick and Campbell Scott have a nice chemistry together. Around lunch time, we step out into the daylight. I see problems. Campbell still looks like a leukemia victim. We still have two weeks. What kind of vitamins make hair grow?

Today, Bridget Fonda and Matt Dillon arrive in town. Matt, who will play a Seattle musician named Cliff Poncier, has already spent time in New York with Mother Love Bone’s Jeff Ament, Stone Gossard and their intensely shy new lead singer, Eddie Vedder. Their new band is called Mookie Blaylock, after the New Jersey Nets basketball player. [Later they’re renamed Pearl Jam.] In the movie, they will play Cliff’s fictional band, Citizen Dick. Matt has already got a lead singer’s walk down – all attitude, chest puffed slightly out. I wanted rehearsals to begin weeks early so the cast could soak up the local atmosphere and the music.

Tonight we go see Mookie Blaylock and Alice in Chains performing at the Off Ramp. The cast meets for the first time in the lobby of our hotel. For a few minutes, nobody says much. (“I hope this isn’t a yuppie movie,” Matt announces, picking an odd conversation opener.) We go to the club. It’s sweaty and packed, and the cast slowly makes friends as we sit in a corner booth.

2-27-91: We read through the script today, and it sounds good. Afterward, the cast hangs around in my office, with downtown Seattle as a backdrop. They’ve become friends. Six months of casting is paying off. It’s still mind-bending, though, to see the characters you’ve written sitting around and talking in character.

3-1-91: Campbell’s hair is shaped. It’s like shortening the legs of a table. In the process, more is mistakenly cut.

3-9-91: Campbell’s hair is becoming a flash point. I sense he’s picking up on it. Rehearsals fall apart.

3-10-91: Nancy [my wife] tells me I talked continuously in my sleep. “Sick hair,” I said, over and over.

3-11-91: Kyra is in the first scene, and she’s like clockwork; she’s excellent. We have a celebratory lunch with the cast – except for Campbell, who has disappeared.

3-12-91: Campbell shows up this morning to report that he married his longtime girlfriend Anne over the weekend. What a way to start a movie called Singles.

3-13-91: No sleep. Warner Bros. see the dailies. “Campbell Scott looks sick,” they say.

3-14-91: I’m keeping the studio’s panic from Campbell, but he senses something is wrong. He’s starting to make odd cracks and barbed jokes; they fire in every direction. It’s getting under my skin. I take him aside and ask him what the problem is. He is instantly apologetic. “It’s my sense of humor,” he says. Later in the day, a WB executive calls and suggests replacing him. I stand by Campbell and hope for sun and speedy hair growth.

3-17-91: I call Campbell and suggest a wig. He takes it well, but just beneath the surface I feel his anger. I admire actors; it can’t be easy approximating real life with a huge, glowing camera in your face.

3-18-91: Jim True, the celebrated stage actor from Chicago, is loose and funny as the maitre d’ and amateur Francophile named David Bailey. True has had rough luck in movies. His performances in smaller parts were trimmed from The Accidental Tourist and Fat Man and Little Boy. It will not happen in this movie.

Campbell says there is a wig he wore for a photo in Dying Young. It looked very realistic. Calls go out: Get that wig. In the meantime, he finds a strange long-haired wig on the set and casually strolls around wearing it. His self-effacing move defuses the pressure. He wins everybody over. What a roller coaster.

3-22-91: The Dying Young wig arrives. Campbell and I work on his look in the hair-and-makeup trailer. Nobody is allowed to see him. Finally, when the wig is right, we test it out. Seattle actor Johnny “Sugarbear” Willis arrives for a small role and, knowing nothing of the hair crisis, tromps into the trailer. He chats with us for five minutes about crab fishing. We seem to be getting away with it. Then Johnny leans forward, eyeing Campbell carefully. “That is not your hair, man,” he says.

I meet Campbell out in the hallway and tell him we’re going to go with his real hair, shortness be damned. Back to the trailer we go. In the three days we’ve take to find his wig, Campbell’s hair has grown just enough to work.

3-27-91: I’m starting to sound like Matt Dillon. It’s infectious, his New York jukebox accent. For all his tough-guy parts gone by, he is a loved actor on the street. Strangers tell him they’re “chillin’ like Matt Dillon.” He takes it all in with a bemused grin. He was slow to commit to the part of Cliff Poncier, but now he’s here, and it feels right. Walking around the set in his GREEN RIVER T-shirt, he looks perfect. A dedicated music fan, his trailer blasts with Tyrone Davis, the Replacements and the Clash. He’s brimming with ideas.

“I love Bridget,” Matt says several times today. “I’m in love with her.” I think he means it. He’s anxious to play a reversal on the usual romantic male lead. In this movie, he will pursue the girl. (“And I don’t want to smoke; I see my old movies, and I’m always smoking.”) He’s almost always dead-on with his first take, and if he isn’t, somewhere around take 5 he might disappear around the corner. Then you might hear the sound of someone slugging a wall with his fist. Returning with laserlike concentration, Dillon’s next take is usually perfect. His knuckles are bulky reminders that he’s been acting almost nonstop since he was fourteen. “Sometimes I’m hard on myself,” he says. “No big deal.”

3-31-91: Easter, a day off. I look out the window at the water, and the sky goes blue. Two things about Seattle: One, this whole town is jacked on coffee, and two, on the right day it looks like the cover of Houses of the Holy.

4-1-91: The Bridget Fonda phase of filming is kicking in. She plays Janet Livermore, the architecture student killing time in an espresso job. Janet is in love with love, and I wrote the part for Bridget. For months, in person or on the telephone, we’ve discussed every aspect of Singles. Like a dry young Barbara Stanwyck, she nailed down every small detail of Janet’s life. Seeing her finally do the part, I realize she’s deceptively low-ball. From three feet away, it appears like she’s not even acting. Seeing the same thing on film the next day, she explodes.

The dialogue involves the love-stuck Janet trying to figure out how and why Cliff could be less than electrified by her. Very directly, she asks him a private question: “Are my breasts too small for you?” In the script, it was surprising and funny. As performed by Matt and Bridget, it’s achingly real.

4-4-91: Tonight the studio calls to say the movie is getting serious. This is probably not a compliment.

4-8-91: “Kyra is in tears,” says the production assistant. In her trailer, Kyra confesses that she’s not sure how she’s doing playing Linda. Haven’t I been telling her all along? “Yes,” she says, “but you’re so enthusiastic that when you get quiet, I get worried.” She’s right, of course. I have been quiet. My working relationship with Campbell is deteriorating daily. The air is thick with the unspoken. I know it’s not easy for him. Steve Dunne is the hardest part in the movie. All around him are characters with odd and interesting quirks. He is the Curse of the Normal Guy.

4-9-91: The day ends with the last scene of the movie – Matt and Bridget alone in the elevator. It’s a romantic scene, and it has some intricate timing. We film it fourteen times. Between takes, Bridget pluckily explains that kissing scenes are much easier when she actually likes the guy. “He’s a sweetheart,” she says of Matt.

4-10-91: Finally, the confrontation with Campbell. The hostile humor is creeping into his performance. “And who are you?” he says, when I try to talk with him. I am mystified again by humor behavior, even as I stand here trying to direct a movie about the mysteries of human behavior. A few minutes later, while the camera is rolling, Campbell cavalierly flips off camera assistant, Shawn Hise as he snaps the slate. (Shawn looks wounded; he’s a Campbell fan.) That’s it. I take him aside and tell him again to knock off the endless sarcasm. Campbell goes off, his voice booming. He’s pissed off at the way actors are treated. He wants actors everywhere to be understood. The sheer volume of his voice is astounding. And then it sort of sinks in…. He’s yelling at me. I cut loose myself. I start yelling at him. It’s freeing, and he backs down. In fact, he seems grateful. Now we just want to make friends again, like two guys who just had a fender bender and, their hearts racing, have to bond over the crisis. He tells me he respects me, he thinks I’m a great writer. Pointedly, as thirty waiting crew members pretend they’re not listening, he doesn’t add the occupation I’m currently pursuing – directing. Maybe I’ll just be a writer. This part of it, when blood is in the water, is not my favorite.

4-11-91: Mark Arm from Mudhoney brings Sonic Youth on the set. They arrive on an important day. Today is the French Club scene. It has been the target of countless assassination attempts in story meetings at the studio. (“Take it out. I’ll never end up in the movie.”) The scene survives because they are wrong. Proudly, I collar [Sonic Youth guitarist] Thurston Moore. For some reason, I feel the need to explain the French Club scene to him in great detail. He nods courteously. His eyes glaze. Thurston invites us all to their big concert tonight with Neil Young. Can’t wait for this show.

4-12-91: Passed out in the hotel and missed the show.

4-19-91: This movie is a freight train. Eric Stoltz has joined us for a few days. During Fast Times at Ridgemont High, Stoltz once promised to be in “everything you ever write.” In Singles he plays a Bitter Mime. Typically, he is twisted and savagely funny in the part. Stoltz and Bridge are a couple in real life, they’re good together, their relationship seems destined for a life outside of news photos.

It’s a loose and goofy night, and we finish a ton of work. By 4:00 a.m., Campbell, Eric Stoltz and I are doing Michael Bolton impressions. Bolton sings Zeppelin. Bolton sings Guns n’ Roses. We are all so tired that just the word – Bolton – sends us into hysterics.

4-22-91: The studio calls and floats a (lead) balloon. Isn’t the title Singles “dated”? Isn’t there a popular song that would be better? I hope this issue goes away. Jeff Ament comes to the set at lunch time with the first rehearsal tape of potential songs for the movie. Mookie Blaylock is now Pearl Jam. The first song, “State of Love and Trust,” is ferocious. It’s about battling with your instincts in love (“… help me from myself…”). Somehow it matches the movie-in-progress. The tape contains four other new Pearl Jam songs. A little over a year after losing Andy Wood, Ament walks with quiet pride. Like maybe lightning is striking twice.

4-28-91: We film Alice in Chains playing live at the underground club Desoto. It’s a boost. I can’t tell you much about the precise filmic style of John Ford’s westerns, but I can tell you about the pure emotional perfection of Todd Rundgren’s Hermit of Mink Hollow or the Replacements’ Tim, Mother Love Bone’s “Crown of Thorns” or even the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds. To get the feeling watching Singles, that would be something.

4-30-91: The Car Crash scene goes well. Today I overhear two grips having a conversation about me on the radio-mike headset. I hear that I look especially happy today, that I must have gotten laid last night and that after all the talky scenes it was great to get out there today and “T-bone that fuckin’ car.”

5-24-91: Tonight is the wrap party. Extras are starting to get drunk now, telling me how this has been the best time of their lives. Where was I? I feel like I blinked and the whole thing was over. I am proud to have made a movie in which Bridget Fonda shares a scene with legendary Sub Pop thrash rocker Tad. But now our de facto family is breaking up. Movie-crew people are nomads. They’ll go on to three or four more movies, and I’ll still be with the child Singles.

7-23-91: Today is the day we look at the first cut of the movie. It’s two hours and forty-five minutes long. Parts are thrilling; parts make me squirm. Back in the editing room with Richard [Chew, our editor] and Art [Linson, executive producer], we attack the problems. Nothing is as funny as we’d hoped. Everything feels long. Oddly enough, I don’t feel panicked.

9-9-91: I’m staring to panic. Perspective is slipping away. I’m lucky to have Richard, a careful editor, a protector of characters. Forty minutes have been take out of the movie. I hope it’s the right forty minutes. I know this – the French Club scene is staying in.

10-4-91: I have reached tunnel vision. It’s a strange syndrome. All I do is watch Singles. The only people I see are crew people who watch Singles. I want to go out with my wife, maybe to see The Fisher King, but I can’t. It’s too dangerous. I might feel bad about Singles. I am Bubble Man. All I can see are bona fide classics from another era – which don’t count – or very bad contemporary movies. I stay home and watch Elvis in Live a Little, Love a Little, and all is right with the world again.

10-30-91: Whatever cockiness that surfaced, and was deliciously enjoyed, a few months ago is disappearing fast. Every conversation with the studio lately is about the Cards. The future course of this movie will be by 400 Glendale [California] moviegoers between the ages of seventeen and thirty-four, recruited mostly at malls. They will fill out … the Cards. The Cards are then tallied, and the result is what WB is truly after … the Numbers.

11-6-91: Today is the first preview. I get a speeding ticket. I’m a mess. I inch toward the preview, feeling very nervous. The movie begins on time; the audience seems to really pay attention. Then, a restlessness sets in. I die with every walkout. I study the way they walk. Are they going to the bathroom? Will they come back? COME BACK! (Most do.)

The Numbers are average. There is an immediate and powerful desire to point fingers. Typically, I think I’ve run from the raw emotions in the movie. I went for the jokes. I’m reminded of words I’ve heard from close friends my whole life: “I don’t know when you’re kidding and when you’re being serious.” Tonight, I think it’s true of Singles.

11-11-91: I show the movie to a trusted friend, and his reaction is eye opening. “I’m with the movie,” he says, “and then something gets lost. You don’t ever fully explain why Steve and Linda break up.”

11-24-91: It’s true. We’re still missing a definitive breakup sequence. I’ve asked WB to let me shoot these new scenes. Since our first preview, I’ve felt the unmistakable studio chill. It’s predictable. WB is in the business of making big, big hits. They are in the rhinoceros business, and I am an ant. It’s not us, they seem to say; it’s the Numbers. An old friend sees me; he’s shocked at my appearance, tells me to get some sleep.

12-7-91: Paul Westerberg records a new song, “Dyslexic Heart,” in Los Angeles. It’s classic Westerberg, all about love and confusion, and it’s the perfect song to end the movie. Elsewhere, Warner Bros. agrees to the shooting of the new breakup sequence.

12-19-91: I agree to take the French Club scene out for one screening.

1-1-92: Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell sends in a rich collection of incidental music. This movie takes music like a sponge. For me, Cornell is the very soul of Seattle music and its endearing darkness. I remember him the night Andy Wood died. He put a hand on Jeff Ament’s shoulder. “I’m gonna call you tomorrow,” Cornell said, angry at the world. “We’re gonna ride bikes and fucking smoke cigarettes.” It’s an odd moment to remember so clearly. Something about it just nailed this city.

1-8-92: Back in Seattle, shooting the new material. Campbell’s biggest scene takes place in a pay phone, as he leaves a lengthy, impassioned message for Linda Powell. After a handful of takes, we have it; it’s finished. I walk Campbell up the steps. I still have a little wetness in my eyes from the scene. It’s one of those awkward moments. We’re probably supposed to hug, do something emotional, but we’ve burned each other out. We nod respectfully and quickly head off in opposite directions.

1-20-92: Sadly, I agree to leave the French Club scene out for one more screening.

1-23-92: “This is a good theater,” whispers Art Linson. “Even Bonfire of the Vanities previewed well here.” My heart sinks. This second marketing preview takes place in Marina del Rey. (Can we ever show this movie outside of Los Angeles?) I feel like I’m in court. I sit at the back, right behind WB president and COO Terry Semel, who is seeing the movie for the first time. Singles plays well; the audience is alive. Then, heading into a dramatic section of the movie, two 15-year-old guys in HARLEY shirts get up and head for the lobby. Executive heads turn. They’re not seeing two 15-year-olds leave; they’re seeing a nation of 15-year-olds leave. I look down. I’m dying. I turn to Nancy. “I’m dying,” I say. She reminds me that it was worse when we previewed Fast Times at Ridgemont High.

“What did I say then?” I ask her.

“‘I’m dead.'”

In front of me, Terry Semel twirls a piece of popcorn and brings it slooooowly to his lips. This more complex version of Singles holds the audience’s attention, but there is only tepid applause at the end. Standing, waiting for the Numbers, the mood is dark and brutal. The Numbers arrive. The scores go up modestly. “We’re not reaching the Young Males,” says one executive gravely. (I heard this on Say Anything.) “But you got yourself a star,” say another. “Campbell Scott.”

1-24-92: WB has offered new title suggestions: In the Midnight Hour, Love in Seattle, Leave Me a Message and a grim selection of others. It’s all done politely, of course, but the pressure is unmistakable. Now, with the success of Nirvana, they’ve come up with yet another title: Come as You Are. I am powerless to stop them.

2-7-92: There is confusion about how to sell a realistic movie about love in a Lethal Weapon world. I tell the marketing executives that Singles is a movie for college-age audiences. They don’t believe me. Their research says the movie appeals to Young Girls. We have lost our April release date. Singles is adrift.

I have to put all this out of my mind. We have looping to do with Campbell Scott. Our past scrimmages still hang in the air. He asks about this journal. I tell him if it ever gets published, it shouldn’t be a fluff piece. “Write about us fighting and everything,” he says.

2-10-92: My stealthlike attempt to return the French Club scene to the movie is thwarted by Richard Chew.

2-13-92: L.A. is in the midst of an intense thunderstorm. Our third preview goes well nonetheless. The Numbers inch upward. (Tonight, the rating goes up with Young Males and down with Young Females. A new corporate panic sets in.) I’m happy, although I feel that there is still something missing at the end.

I read the Cards for an answer. I get the creepy feeling that the same 400 people are shaping the movie … and every movie. To read their comments, they seem drunk with the power … or maybe just drunk. “More wicked tit,” says a fourteen-year-old, who also adds that he’s married. A nineteen-year-old who checked the boxes “Male” and “Female” (“I’m bi”) as well as “Black” and “White” (“Nabisco Oreo”) writes in large, looping letters: “I love the sexual activity and the hooters. I love the Anal Fury. The music was awesome, bra.” This one goes on my refrigerator. It’s hard to read this stuff. It’s like hearing people talk behind your back. I’ve got to remember the goal … a personal movie about relationship, a collage of lives and emotions. “It’s honest,” says another girl. I want to kiss her. I’ve got to sleep a little, wipe the stress off my face. What is Anal Fury?

2-16-92: Sleep comes in small bursts, as I dream of an intricate movie version of Hawaii Five-O. Even my dreams are trying to be more commercial… The studio is not impressed with the Numbers. They are full of suggestions on how to make the movie more palatable. I have made the right movie for the wrong studio.

This is the biggest crime of test marketing. It hits directors at their most vulnerable time. You start out proud and alone, defending your vision. By the end, you’re wobbling on two rubbery legs, obsessed on how to reach Young Males. It’s a trap. Suddenly, all poetry is replaced by equation. All you want is to survive, to get those Numbers up. To get your movie released.

4-1-92: The last marketing preview will help determine our release. The screening goes well. The Numbers change only slightly – but supposedly in important ways. “We’ve got the Young Girls back,” declares one executive, but it’s clear they’ve written off their highest expectations. They have pigeonholed the movie as appealing to Young Girls, and that’s that. A flash of perspective hits me during the screening. The movie needs to be set in context. Privately, I vow to restore the original ending, a voice montage of people all over the city, everywhere, obsessing about love. Singles is not just about six characters; it’s about a world of people needing to make the connection. That’s the last piece of the puzzle.

4-9-92: Still no release date. A year after filming, the world has caught up with the bands and the music we built this movie around. Pearl Jam and Soundgarden and Alice in Chains have all exploded. Epic, the label releasing our soundtrack, moves to put the music out now. WB agrees, and they quietly default into the only real title of this movie, Singles. The hometown music that helped inspire the script is now our best ally in getting the movie released.

4-13-92: New York City. Campbell and Kyra have come in for the last of many looping sessions. On their faces is the same look I’m seeing from almost everybody. … Let go. “Is the French Club scene still in the movie?” Campbell asks. Agonized, I can hardly tell him no. We wish each other the best. There is plenty that could be said; maybe we’ll say it another time.

5-15-92: Today, we will screen the movie one last time for ourselves. It’s the first time we will view the new ending, with the myriad of voices (provided by friends and nearby assistants). We’ve been mixing it for days, crafting the level of each voice. If it doesn’t work, we don’t have the time or money to fix it. Watching the complete movie for what must be the sixty-third time, my foot bounces wildly in anticipation of the new ending. It arrives. The voices build, all over the city, until it’s one glorious din. Finally the movie makes its case for love. Finally we have an ending – and just in time.

5-22-92: We’re in New York for three screenings, the first time the completed movie has been shown outside of Los Angeles. It is the first time we’ll show it to a (mostly) college-age crowd. There is loud, heartfelt applause. Hearing it now, in New York City, is a real high. Jokingly, I later tell Richard Chew that I want to put back the French Club scene. “No,” he says. A good-humored man, I have rendered him humorless on this subject. I will say this about the French Club scene, and then I will let it go. There’s always laser disc.

5-23-92: When will filmmakers fight back against the damning effect of market research? Why is Singles still adrift? We continue to fight the currents. First, the Numbers … then the Cards … then the Release Schedule. Maybe this is Anal Fury.

6-2-92: “Congratulations,” says the smooth voice on the telephone. “You have a release date.”

I’m packing my desk to move out of our office. We’ve been in postproduction for over a year. There are stray artifacts from the filming – Steve and Linda’s pregnancy test, Cliff’s guitar picks and then a strange-looking hatbox. I reach inside.

It’s Campbell’s wig. I pick it up. Except I don’t see a wig, I see the making of this movie. I see every expectation, dashed hope, every exciting and exhausting aspect of filmmaking. How fragile the whole process is. The movie is finished, and I’m proud of it. Soon it will have a life of its own. I pack the wig in the back of my car. Like any great obsession, Singles dies hard.

Tonight, I’ll sleep.

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #640 – Cameron Crowe – October 1, 1992