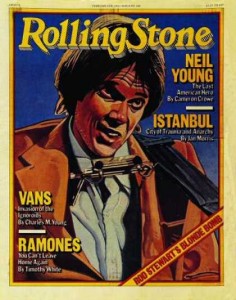

Rolling Stone #284: Neil Young

Neil Young: The Last American Hero

It was supposed to be something holy, for God’s sake, when old Ernie sat down at the piano… I swear to God, If I were a piano player, or an actor or something, and all those dopes thought I was terrific, I’d hate it. I wouldn’t even want them to clap for me. People always clap at the wrong things. If I were a piano player, I’d play it in the goddamn closet. – Holden Caulfield, The Catcher In The Rye

My parents occupied the bedroom directly above mine while I was growing up. Luckily they were heavy sleepers, and loud music late at night didn’t seem to bother them much – unless, of course, it was the high-pitched guitar or vocal work of Neil Young. On such occasions, my mother would trudge downstairs, rap at the door and stand there with a look that suggested the wrath of every deprived sleeper over the ages.

“Are we going to listen to this man baying at the moon all night?” she would invariably ask, on behalf of my father and herself.

There was a time, sure, when I tried to explain to them what it was to be a Neil Young fan. “How important is an in-tune vocal?”… “But it’s great when he hits the same note thirty-eight times in ‘Down By The River.'” Here was an artist, as opposed to an entertainer. Here was someone who would never turn up hawking his wares on some talk show.

Neil Young’s popularity would soon speak for itself. In 1972, my parents would hear “Heart Of Gold” played in the supermarket, find it tuneful, and begin to see things differently. When Neil Young announced he would be playing San Diego, our hometown, on a rare concert tour, it became a family outing. My sister, my teenage cousins visiting from Kentucky, my parents and I all went to the show.

Neil Young appeared right on time, nervously walking out in front of the screaming crowd, one arm upraised. He looked skittish and tired as he picked up a guitar and began to sing an acoustic song, one of the first he ever wrote, called “Sugar Mountain.” The audience rushed the stage, shouted for the electric songs and Young called his band out onstage. But instead of Buffalo Springfield chestnuts and standards like “Down By The River,” they played a set of reckless new music, causing no small tension in the arena. Then, during the final song of the evening, the pressure seemed to cause Neil Young to crack. He began to shout, “Wake up San Diego, Get up San Diego….” A few minutes later, the houselights were turned on and the hall was filled with an eerie silence.

“He acts like a drunken monkey,” said one of my cousins. The rest of the family didn’t say much. We didn’t talk about Neil Young for the next few years.

Recently, I found myself back in the same old room late one night, typing this article and listening to Neil Young records, when a familiar knock came at the door.

“Well,” said my mother with a note of sentimentality. “A survivor.”

The fact that Neil Young can barely relate to his successful current album, Comes A Time, is typical of his career, and perhaps one of the reasons he is a survivor. He’s thirty-three and he’s spent twelve years in the forefront of the most fickle of businesses, shattering expectations. “It’s in the middle of a soft place,” he says of the album. “It was made to come out a year ago and got hung up with pressing problems. I hear it on the radio and it sounds nice….But I’m somewhere else now. I’m into rock & roll.” Held up because Young had approved a faulty test pressing of the album, and then bought back $160,000 worth of the already printed record because of his mistake, Comes A Time is a complacent Neil Young album. In the time that it took for the LP to come out, something in music changed. Much of the music made by artists who came to popularity in the Sixties and Seventies began to fall on deaf young ears.

“I first knew something was going on when we visited England a year and a half ago,” says Young. Sitting in the half-light of his ranch home in northern California after the end of his Rust Never Sleeps tour, Young speaks with an urgency. “Kids were tired of the rock stars and the limousines and the abusing of stage privileges as stars. There was new music the kids were listening to. As soon as I heard my contemporaries saying, ‘God, what the fuck is this….This is going to be over in three months,’ I knew it was a sure sign right there that they’re going to bite it if they don’t watch out. And a lot of them are biting it this year. People are not going to come back to see the same thing over and over again. It’s got to change. It’s the snake that eats itself. Punk music, New Wave. You call it what you want. It’s rock & roll to me, it’s still the basis of what’s going on.”

Neil Young had given up on touring and was working on his second movie, a comedy/fantasy/musical called Human Highway, in which he plays a folk singer named Neil Young, when his friend Dean Stockwell (who plays Otto, the manager, in the film) told him about the New Wave band, Devo. Young knew immediately that this was the band he wanted for a nightmare episode in the film. He even had the song they would play together, the new one called “Out Of The Blue” that he’d written with the Sex Pistols in mind (“It’s better to burn out/Than it is to rust”).

Members of Devo were flown in from their base in Akron, Ohio, to shoot the nightmare sequence in front of an audience at the San Francisco punk club Mabuhay Gardens. Devo introduced Young as “Grandpa Granola,” and played the song live and in a local studio before flying back to Akron. Later, listening closely to the tape, Young heard two of the members chanting the phrase, “Rust never sleeps.”

He called them in Akron. “What is ‘Rust never sleeps’?”

Two of the members of Devo, it turns out, used to be in advertising. They had devised the phrase during a campaign for the rust-remover Rustoleum and decided it fit the song. To Young, it fit his very career, and his battle against the dreaded, creeping disease of trying to make a good thing last. Suddenly, Young once again felt the pull of the road, felt the pull of rock & roll. He booked a six-week tour with Crazy Horse, plotted a fully scripted show with filmmakers/directors L.A. Johnson and Jeanne Field, and took off on Rust Never Sleeps.

“I knew I had to get out there and rock,” he says. “But I also knew that I couldn’t see myself out there doing it the way it had always been. Standing out there with a microphone. It’s got to continue to be as new as when it started.

“The music business is so big these days, I feel dwarfed by it. I mean, I put out a record and, you know, it does okay. Somebody like Foreigner or Boston, they come out with a record and sell ten times as many as I do. I think that’s great. But I still feel like this…little guy.”

A set was designed in which huge amps and a huge microphone were constructed before the audience’s eyes by Young’s roadies. Now they were Road-Eyes, dressed in blackface and hoods not unlike Star Wars Jawas. (When Young explained the concept to his puzzled crew, he instructed them to “wave yourself goodbye for a few hours then move with fervor and purpose.” Young himself would play a child dreaming about rock & roll.) Beginning the shows with “Sugar Mountain,” he moved through a cross section of old and new songs, ending with a phenomenally loud set with Crazy Horse. “I wanted people to leave saying that Neil Young’s show was the loudest fucking thing they’d ever heard.” It was a heavy-metal tour de force, and somewhere in the middle of the tour, Comes A Time, Young’s most subdued album since Harvest, was finally released.

“You know,” says Young, confidently, “I do the same thing over and over and over again. It has a slightly different look to it every time. This tour seemed to wrap something up. It’s a retrospective, but it’s looking back on right now. I think I broke through to another arena; now, people won’t be surprised if I enhance the program with actors and diverge totally away from music, then come back out of it into music again. It’s making rock & roll more visible to me.”

He is struck with an idea. “I’m lucky.” says Young. “Somehow, by doing what I wanted to do, I manage to give people what they don’t want to hear and they still come back. I haven’t been able to figure that out yet.”

I first met Neil Young in 1973, on a bus to San Luis Obispo. He had come along to play guitar with the Eagles at a small benefit for the Indian community there. Young sat playing banjo, a grinning cipher in reflector shades. I was instructed not to talk to him, that he had nothing to say. After the show – which climaxed with a fiery “Down By The River” that Young and the Eagles still talk about – Young plopped down in the seat next to mine. His shades were off, and his eyes were dark, sunken shadows below an Indian-like forehead. But they were mischievous, adolescent eyes. Dennis the Menace eyes.

“Hey,” he said, “Bernard Shakey.” We shook hands, and he began to tell me that he was an amateur filmmaker, that he was working on his first film (he was finishing Journey Through The Past at the time) and was a little nervous about it. He talked excitedly, punctuating his words with a smirk. “Tough business. I’d hate to go back to shooting Hyatt House commercials.”

I turned to look out the window, remembering my impression of Neil Young as a depressed loner. Now here he was – a joker. I turned back around. He was gone, of course, and I was right back where I started.

Young must have remembered the conversation or enjoyed my gullibility. Two years later, when he was releasing his most antipop album, Tonight’s The Night, I received a phone call saying that he was ready to do an interview. There was a listening party in Los Angeles, his first-ever such media function, and we made plans over beers to meet at manager Elliot Roberts’ office. I arrived the next morning to find Young, cheerfully cordial, discussing the album with three hungover disc jockeys. “I just wanted to obliterate everything that I was, you know,” he was saying, “and wipe the slate clean.”

After the conference, Young remained on a sofa drinking orange juice and playing with his dog, Art (“Art is just a dog on my porch”). He sized me up and smiled.

“You need some sun,” he said. “You look like people expect me to look. Let’s go for a ride.”

We walked across Sunset Strip and Young rented a red Mercedes convertible for the occasion of his first extensive interview in five years. A sweltering afternoon, we took a ride out Pacific Coast Highway. After a few attempts at small talk, Young turned and announced: “My uncle played ukulele. Outside of that, I don’t really come from a musical family.” There was a lengthy silence. A car full of surfers made a dangerous swerve through traffic to pull alongside for a look. “Hippies,” he cracked.

I asked him about his childhood, a question that met with a good two minutes of silence. I began to wonder if the interview was already over. Young was born in Toronto, the son of a sportswriter for the Toronto Sun, Scott Young. Young’s parents split up when he was ten, and Neil moved to nearby Winnipeg with his mother, Rassie.

“I know the newspaper business,” said Young, who was a Sun paperboy. “I had a pretty good upbringing. I remember really good things about both my parents. I don’t feel the need to communicate all that much with them. I think back on my childhood and I remember moving around a lot, from school to school. I was always breaking in.” He looked over. “I liked to play jokes on people.” Jokes?

“Same old shit,” he continued talkatively. “Once, I’d become a victim of a series of chimp attacks by some of the bullies in my room. I looked up and three guys were staring at me, mouthing, ‘you low-life prick.’ Then the guy who sat in front of me turned around and hit my books off the desk with his elbow. He did this a few times. I guess I wore the wrong color of clothes or something. Maybe I looked too much like a mamma’s boy for them.

“Anyway, I went up to the teacher and asked if I could have the dictionary. This was the first time I’d broken the ice and put my hand up to ask for anything since I got to the fucking place. Everybody thought I didn’t speak. So I got the dictionary, this big Webster’s with little indentations for your thumb under every letter. I took it back to my desk, thumbed through it a little bit. Then I just sort of stood up in my seat, raised it up above my head as far as I could and hit the guy in front of me over the head with it. Knocked him out.

“Yeah, I got expelled for a day and a half, but I let those people know just where I was at. That’s the way I fight. If you’re going to fight, you may as well fight to wipe who or whatever it is out. Or don’t fight at all.”

He looked over again, offering me a vision of my own amazement in his shades.

“Few years later, I just felt it,” he concluded cheerfully. “All of a sudden I wanted a guitar and that was it.”

In his midteens, Neil Young hit the Winnipeg dance-band circuit with his band, the Squires, and his own songs – stinging instrumentals heavily influenced by the Shadows and the Ventures. Then came the Beatles and Bob Dylan, and Young started to write lyrics.

“I never forgot,” he says, “that every time a new Beatles or Dylan album came out, you knew they were way beyond it. They were always doing something else, always moving down the line.”

Moving back to Toronto, Young soon took up a twelve-string acoustic guitar and tried folk singing around the coffeehouses. He made friends easily with other musicians like Stephen Stills, Joni Mitchell and Richie Furay, who were traveling along the same path. Mitchell wrote “The Circle Game” for him after hearing “Sugar Mountain,” which was about growing too old to get into the local teen club.

Rock & roll, meanwhile, was booming. One of the biggest bands around Toronto was a group called Ricky James and the Mynah Birds. “We played rock and blues,” James, now a disco star, recalls in Los Angeles. “I remember our first gig,” continues James. “When Neil took his first solo, he was so excited he leaped off the stage, the plug came out and nobody heard anything.”

The Mynah Birds broke up after a flirtation with Motown when James, AWOL from the navy, was pressed back into the service. Their young career at a standstill, James and Young spent a teary afternoon promising each other that they would form another band after James returned. “It was heavy, man,” recalls James. “I had really gotten close to the cat. He was never very healthy – he got bad epileptic fits sometimes – but he had balls like you wouldn’t believe.”

After a few months, money ran out and Young had to sell the Mynah Birds’ equipment. Typical of his sense of humor, he used the money to buy a long, black Pontiac hearse and headed for Los Angeles with Mynah Birds’ bassist Bruce Palmer. Neither had working permits or the proper papers. “But if you were looking for a break,” says Young, “the great Canadian Dream is to get out. So we came down anyway.”

They were lumbering down Hollywood Boulevard when the Ontario license plates were spotted by two folkies Young had met up in Canada. Stephen Stills and Richie Furay pulled Young and Palmer over. There, on the street, they talked of their stalled careers. Stills and Furay’s folk group had broken up, Stills had even failed an audition to join the Monkees because of his teeth. They decided to form a group, later adding Dewey Martin on drums. They named themselves after a tractor, the Buffalo Springfield.

“Stills and I have always gotten along,” explained Young on his bus during his 1976 tour, as we headed for a show in Madison, Wisconsin. “I just had too much energy and so much creative flow coming out that when I wanted to get something down, I just felt like, ‘This is my fucking trip and I don’t have to listen to anybody else’s.’ I’d do what they wanted with their stuff, but I needed more space with my own. And that was a constant problem in my head. So that was why I had to quit. Then I’d come back ’cause it sounded so good. I just wasn’t mature enough to deal with it. Everything was going much too fast.”

By late 1968, the intense chemistry of the group had lit a fire under all its members. Everyone had scattered in different directions, leaving bassist and then engineer Jim Messina to assemble the band’s third and final album, Last Time Around, at Sunset Sound studios. While Young was recording, though, Joni Mitchell was down the hall, beginning her first solo album produced by her then-boyfriend David Crosby.

“I don’t really want to go down there,” said Crosby at the time. “That guy Neil Young is strange.”

Mitchell turned to her manager. “Elliot,” she said, “you have to meet Neil Young. You’ll love his sense of humor.”

The possessor of a mercurial wit, Brooklyn-born Elliot Roberts immediately hit it off with Young. “Everybody was intimidated by Neil,” says Roberts. “I heard all these stories – Neil had left the band twice….Everyone was always on eggshells around Neil. Say the wrong word, he’s gone. That is all I ever heard. Well, I found it easier to deal with Neil than Stephen. I used to tell people the funny things Neil had said. They’d say, ‘Neil?'”

After the Springfield’s demise, Roberts became Young’s manager, and launched him on a solo career. Roberts tested Young’s appeal by getting him a guest appearance during a Dave Van Ronk show at a Pasadena nightclub. “We stayed up all night because we were so thrilled he didn’t get booed off,” recalls Roberts. “He hated his voice and thought all his songs were depressing.”

After the Springfield,” Young said during that ride on his tour bus, “I wanted to get out to the sticks and think everything over.” Along with his wife, Susan, Young moved into a spindly house high atop a hill in Topanga Canyon. After finishing his first solo album, Neil Young, in a local studio – which, these days, he fondly characterizes as “Overdub City” – he built his own studio in his garage.

“The problem was, I needed a band again,” Young said. “I met these guys that were, to me, the American Rolling Stones. There has never been a bad night with them, to this day. Crazy Horse.”

Danny Whitten was the leader of Crazy Horse. A husky, blond guitarist/surfer, the intensely sensitive Whitten wrote all his songs about the same sixteen-year-old girl who had broken his heart. He had moved to California from back East with Ralph Molina and Billy Talbot, as part of a vocal group called Danny and the Memories.

“You had the impression,” Elliot Roberts recalls, “that he had been through a lot and was very soulful. Whatever very soulful is, he had it. Very strong guy, but you could see that you say the wrong word and you’d slap him in the face. We all liked Danny. He was obviously very talented and Neil was drawn to him instantly.”

Young met Whitten through a mutual girlfriend while he was still with Buffalo Springfield, and they began playing together. Whitten’s guitar playing cut slashing patterns across Young’s. After working on the first Buffalo Springfield album during the day, Neil fell into the habit of dropping by Talbot and Whitten’s house in Laurel Canyon at night. “We used to have a great time,” remembers Talbot, “sitting around, singing ‘Mr. Soul’ in D-modal turning – all four of us singing harmony.”

Young eventually enticed Whitten, Talbot and Molina to come up to his Topanga home/studio and record some “strange songs” he’d written while being laid up with the flu. “In a single day,” Talbot says, “we did ‘Cinnamon Girl,’ ‘Down By The River’ and ‘Cowgirl in the Sand.’ There wasn’t much need to discuss it….”

Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere – still Neil Young’s favorite of all his albums – was finished in two weeks. He and his new band toured small halls as Neil Young and Crazy Horse, and together they built a lasting reputation for hard, metallic rock. Young would spin off on searing guitar solos during which he wildly tipped back and forth on his heels. Because he acted so quickly, Young was never considered as a leftover piece of the Buffalo Springfield for long.

Neither was Stephen Stills, who had meanwhile teamed with David Crosby and Graham Nash to record Crosby, Stills & Nash. When the trio finished their album and realized they needed another guitarist to hold up the instrumental end of things on the road, Stills visited Neil Young. Just beginning his career with Crazy Horse, Young knew he had a decision to make.

“I decided to do both,” Young has said. “The obligation with Crosby, Stills and Nash wasn’t’ going to be that heavy, a few songs and lead guitar.” It became much, much bigger than that. Or, as Billy Talbot says, “Neil joined up with those guys, man, and everything went crazy.”

Young punched the clock twice a day for a year, touring with Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, then Crazy Horse, then CSNY again. “I never really fit into CSNY as well as Joe Walsh does with the Eagles,” he explains. “Everybody had a different viewpoint on what’s happening and it takes a whole lot to get them all together. It’s a great group for that. Four totally different people who all know how it should be done, whatever it is.”

Young went straight from Deja Vu, the first CSNY album, into recording his own third solo album, inspired by actor Dean Stockwell when he unraveled a screenplay idea of his. It was about three lives – one of them a moody musician – on the day that a mythical tidal wave swallowed Topanga Canyon and was called After the Goldrush. The apocalyptic theme influenced the bulk of material for Young’s album of the same name.

“The film fell through,” says Young, “and there I was with a record. So I put it out. Would have made a great movie.”

It was a more poetic album than Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, due in part to the fact that the tenacious, black Les Paul guitar he played throughout the previous album had been lost. “I took it to this store to be repaired,” says Young. “I came back to pick it up the next week and the store was gone.”

Young chose an enigmatic cover for the album, a solarized shot of him passing an old lady on his way to a CSNY show in New York City. It symbolized his own passage, his breakup with wife Susan and a farewell to the Topanga house that had already started to become overrun with fans (“I came home to find people I didn’t know in my bedroom”). The album captured a huge audience for Young as a solo artist, and that success brought more changes than he could have ever planned for.

“By the time Young did After the Goldrush, he’d fired us,” says Billy

Talbot. “Danny was doing…you know.”

Talbot jabs his arm.

“I was really surprised when Danny became a junkie. There was no reason. In those days, people just started shooting right up. Didn’t snort nothin’. He just shot some speed, the next day some smack and from then on, he was a junkie. He was always a strong person and he was also a strong junkie. Did more than anyone else, they tell me.”

For all his disheleved looks and maybe-I-know-where-I-am-maybe-I-don’t stage presence, Neil Young is not a drug case. For a long time, according to friends, he would ask, “Is this hard grass,” before accepting a joint. (“When I get high,” he says, “I’m a basket case.)” He has never taken acid and never tried heroin. And Whitten’s strong aura of junk scared Young considerably – in fact, he wrote “The Needle and the Damage Done” for him.

With After The Goldrush just released, Neil Young embarked on a solo acoustic tour of small halls, performing the best of his old work and a slew of new songs, written about his new ranch in northern California and a new love. During a stopover in Nashville to tape The Johnny Cash Show, he began recording a follow-up to After the Goldrush. Spiriting away the show’s other two guests, Linda Ronstadt and James Taylor, he recorded “Old Man” and “Heart of Gold,” with Taylor on banjo, at a local studio. But a lingering back ailment worsened as he continued on the tour, and after it ended, Young suffered a slipped disk on his left side. He underwent operations and a long confinement on his ranch. Doctor’s orders allowed him only four hours a day on his feet.

“I tried to stay away from the success as much as possible,” Young says. “And being laid up in bed gave me a lot of time to think about what had happened. I thought the popularity was good, but I also knew that something else was dying. I became really reclusive.

“There was a long time when I felt connected with the outer world ’cause I was still looking. Then you get everything the way you want it. You stop looking out so much and start looking in. And that’s why in my head I felt something change; I was thinking about all these things. I was lying on my back for a long time. It affected my music. My whole spirit was prone.” The lethargic downbeat of much of Harvest, Young’s next album, was partially a result of the sedation he was under during much of the recording. Released in February of 1972, it was the biggest-selling album of that year and influenced an entire genre of country rockers.

Young’s back gradually improved; he began writing and playing electric guitar again, and used some of his wealth from Harvest to finance his movie, Journey Through The Past. In the fall of 1972, Young decided it was time to end the seclusion and undertake his biggest tour yet – three months long and recorded every night for a live album (Time Fades Away) of new material. Jack Nitzsche, the producer of his first solo tracks, was on piano; the Nashville rhythm-section core from Harvest – Kenny Buttrey on drums, Tim Drummond on bass and Ben Keith on steel guitar; and the rumored-to-be-healthy-again Danny Whitten on lead guitar. A huge crew of technicians was brought in, and the mammoth tour began rehearsing at Young’s Broken Arrow ranch.

Danny Whitten was the last to show up, still in the full throes of kicking his habit “city style” – with numbing quantities of booze and drugs. The band started rehearsing, and Whitten soon stopped and propped himself up with his guitar. “You guys are really great,” he gurgled in wonderment. He looked at the sheet music Young had studiously written out for the musicians. “Hey Neil, where’s my music stand?” he demanded and broke up laughing. “Hey Jack! Play ‘Be My Baby.'”

Whitten was driven to the airport, given a plane ticket and fifty dollars. Arriving in L.A., he used the money to score a dose of pure heroin. Danny Whitten shot it up and died that night.

Neil was pretty strange on his big tour,” recalls former tour manager Leo Makota. “He’d already been through heavy changes with Danny, then Neil tells him to go and Danny reads that as him just not having it anymore…and kills himself. It’s like playing God. And are you ready to play God? But that was just one thing that happened.

“Neil was trying to get a certain sound out of the band that he apparently could never find. The band would jam at sound checks in the afternoons and sound great. Then they’d come in and do the show at night and never make it. Neil’s mood never seemed happy or comfortable. So you have a situation where everybody is trying to please him and nobody really pleased him.” One reason, conjectures Makota (who is now a carpenter), is that everyone got a little money-hungry seeing those full houses every night. The band revolted, wanting more dollars and a percentage. Makota himself tried negotiating for a bigger crew price. “I admit,” says Makota, “we should have just done the job that was at hand.”

The revolt took Neil by surprise. “It turned him against everything,” Elliot Roberts recalls. “He didn’t know how to handle his friends constantly hitting on him for more money. He rebelled against the success, started to see what it did to people. I was afraid to leave. I knew if I left, Neil was gone.”

Meanwhile, puzzled audiences were treated to ragged versions of his new songs. (“Every time I go out on the road,” Young says now, “the album that just came out is behind me. I don’t want to lose the time frame to old material.”) Young took to drinking tequila to relax. All those expectant faces waiting for “Heart of Gold” began to look, as he would later write, like an ocean of shaking hands that grab at the sky. They were his demons. And, in Cleveland, he began to scream at them. “Wake up, Cleveland. Get up….” The rest of the tour was biding time.

He returned to the solitude of his ranch, bewildered, saddled with problems from Journey Through The Past and deeply upset. “For the first time in my life,” he says, “I couldn’t get anything to turn out the way I wanted.” It was the beginning of a time he would later call his Dark Period.

There was a brief try at a CSNY reunion in Hawaii in the summer of 1973, but Young left he proceedings because he was “too tired to start another cycle.” Causing no small resentment within the group, Young returned to Los Angeles, where he found another person close to him had ODed – CSNY guitar tuner Bruce Berry. For the first time since Danny Whitten’s death, Young rounded up the remainder of Crazy Horse, and they started recording at a small rehearsal room. The sessions began after midnight, after everyone had drunk enough tequila and played enough pool to do songs in memory of Whitten and Berry. According to Ralph Molina, “a picture began to develop…and it became Tonight’s The Night.”

An album in which tuneful vocals, commercial choruses and artistic humility took a back seat to raw emotion, Tonight’s The Night was rejected by Warner Bros. in 1974 when Young, wearing wraparound, razorback shades, brought the tapes to the executive offices. “I always noticed that Otis Redding would fuck up words on his records, but he’d just keep on going…if the spirit was there,” Young explains today. “Not everyone, however, shares that particular philosophy.”

Young then recorded a slightly more conventional work, On The Beach, but not before taking his rejected album on the road throughout Europe. He assumed the character of a sleazy Miami Beach emcee, a chatterbox of Vegas-type one-liners, and directed the band through a tequila-soaked show.

“I slipped out of myself,” Young recalls, “and into something easier for me to take …. that would destroy what everybody though I was. I don’t like to be prejudged before I do something. I don’t like people to say it’s going to be this, and have them be right. I might have been really slapping the audience in the face with some of the shows, but they had their minds totally turned around and that’s more than you can say for most concerts. It was really healthy for me. I was the same person for too long.

“We tried to put on the entire show for under fifty dollars. ‘Everything is cheaper than it looks.’ was our motto. We hung one light bulb behind the stage. We did everything that we could to get as far out on the edge and try to play our music and to get it loose. I took the Eagles on tour with me – they thought I was pretty crazy. They were a good, clean country group back then, and they sounded like what a lot of people would have expected me to sound like after hearing Harvest. They think, “We’re gonna have an evening of really fine country-flavored rock & roll and folk rock.’ And then we just came out and…took em all to Miami Beach.”

Returning to the States in the wake of a massive critical backlash against him, Young, in a characteristic turn-around, agreed to a huge CSNY summer tour of stadiums. He traveled separately, in a Winnebago, leaving immediately after the show to keep his participation strictly musical. At every turn, though, there were accusations that CSNY had reunited only for the money.

“There’s no question that we got paid a lot of money for doing it,” says Young. “But there’s no question that we were all there and delivered every night. It was just that we were playing these huge fucking places where we could get people to come in like cattle and fucking see us from half a mile away and listen to you squeak. If the wind was blowing the wrong way, they couldn’t even hear you do that. It’s a huge money trip, which is the exact antithesis of what all those people are idealistically trying to see in their heads when they come to see us play. So that’s where the problem is. It costs a lot of money to put the show on. I don’t know where it goes. All of it doesn’t go where it’s supposed to.”

The last CSNY show was at Wembley Stadium in England in September of 1974.

“Sometime,” says Young, “we’ll do something again in some combination.”

After a brief vacation, Young returned to Los Angeles to begin another album, this one meant to be “the other side of Harvest.” The resulting LP was full of the beautiful, melodic ballads his audience had been clamoring for. But the songs were mostly self-pitying, metaphorical details of the breakdown of his most recent relationship. Called Homegrown, the completed album depressed an entire room full of Young’s friends when he played it for them. Someone turned the tape over and played the other side, a resequenced version of the Tonight’s The Night material for a possible Broadway musical. The room began to party again. Rick Danko, of the Band, challenged Young to put Tonight’s The Night out instead. He did.

The album was initially panned by many critics, but by the end of that year, Tonight’s The Night turned up on the best-ten lists of the same critics for whom Neil Young had once symbolized a near comatose laid-back chic.

Says Young today: “It took two years to make it sound like it was made in one night. Everyone thought we’d done this great work. And it still didn’t sell. For me, a perfect album.”

In the spring of 1975, daylight seemed to be breaking through on Neil Young’s artful decline. He recovered the missing Les Paul played on Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere and Billy Talbot called to say he might have finally found a Crazy Horse guitarist worthy of Danny Whitten. Young turned up at Talbot’s Silver Lake home with guitar in hand and heard Frank Sampedro for the first time. Staying for a week, Young played with the refurbished Crazy Horse and wrote material for Zuma.

“Zuma was breaking free of the murk,” says Young. “My best records are the ones with Crazy Horse. They’re the most fluid. Zuma was a great electric album coming from a place where pop leaves rock & roll.”

After finishing the album, Neil Young and Crazy Horse toured the world. “We played England, Japan, everywhere except America,” says Talbot. “It was an idyllic time, man, Neil was just sparkling. We had a band again. I heard us playing like I knew nobody else could play. I remember in Rotterdam, coming offstage and seeing Paul McCartney standing there. We’d just finished the set, the four of us are running through this wind tunnel to get back to the dressing room, and McCartney’s just standing there. He nods at me like, you know, musician to musician. I just kept thinking…four of us. For of them. Have we got a band or what? I don’t think we’ve come down from that tour yet.

“I have this tape from Japan. Compared to this tape, Zuma sounds like a bunch of guys sleeping in big, fat armchairs, smoking pipes. Whenever I feel down, I listen to that tape.”

Sampedro shakes his head. “Some shows Neil gets crazy with the guitar,” he smiles. “Way crazy.”

During a break before the world tour was to continue throughout America, Young found time to begin a long-discussed album with Stephen Stills in Miami. After the project (Long May You Run) was completed, Young took Stills and band on the tour that had been originally planned for Crazy Horse. “Stephen asked Neil to do it,” says Elliot Roberts, “and Neil said yes. He loves Stephen. They’re the oldest of friends… and think about it. In ten years, you’ll be happy to see anybody you’ve known that long.”

But after mixed reviews and the onset of a throat ailment, Young left the tour in Atlanta, with a telegram saying: “Dear Stephen, funny how some things that start spontaneously, end that way. Eat a Peach, Neil.”

Neil Young, who writes virtually all the time, can look back and find all the movements of his life and career documented in his songs, some more cryptically than others. “My songwriting process has never changed,” he explains briefly, as if talking too much about it might betray the muse. “I never try to write. I know when it’s there. I hear a bell ringing in my head and I just leave … but I don’t try. Sometimes three months can go by….” Some artists, I point out, have been known to get writer’s blocks that last for years.

“Well, if that happens to me,” says Young, “I’ll take up gardening.”

One afternoon during a tour several years ago, Young sat in his manager’s hotel room. The phone kept ringing, tour crew members bustled in an out… and through it all, Young sat on the bed with his son Zeke, peacefully watching the news.

The broadcast was interrupted by an emergency bulletin. Pat Nixon had suffered a stroke, an announcer said over a filmed report of the sad and beaten Richard Nixon tearily moving through the hospital’s revolving doors.

After a time, Young got up and disappeared into his bus in the parking lot.

Onstage several hours later, Young played the song he had written:

Hospitals have made him cry

But there’s always a freeway in his eye

Though his beach got too crowded for a stroll.

Roads stretch out like healthy veins

And wild gift horses strain the reins

Where even Richard Nixon has got soul

The song was a first called “Requiem for a President.” Young later changed the name to “Campaigner,” and placed it on his three-record retrospective album, Decade. “Guess I felt sorry for [Nixon] that night,” he said of the song while traveling on his bus the next year, just as 300,000 copies of Decade were being prepared for release within the week. “That album was a chance to use some of the unreleased material. Hopefully it’s a greatest-hits album that’s more like an album.” Young laughed. “Should be timeless.”

I wondered when he’d decided his first decade was over. He thought about that.

“Well,” he said, “I’m not sure it’s over.”

He was silent for a long while. I drifted back to a bunk to watch television. Young joined me after a few minutes and stared at the screen intently.

“Listen to me,” he said, eyes revitted to the tube. “What if I just save Decade for a year, then put out a new album. The new stuff sounds so good – I’ve got this song called “Hurricane” that just soars – I think I’d feel better releasing something new. It’s not time to look back yet.”

I looked over at Young, who had obviously made up his mind and was now fully enjoying The Boy in the Plastic Bubble. A few minutes later, Young went to the front of the bus to make a call on a mobile phone. “Elliot?” I could hear him say. “Here goes another album….”

In two short days, Warner Bros. President Mo Ostin and Executive Vice-President Ed Rosenblatt had flown to the next stop along the tour to discuss delaying Decade with Young. Neil played them most of an album he’d already recorded and titled American Stars n’ Bars (“because one side is about American folk heroes and the other is about getting loose in bars”). They honored his wishes to postpone Decade a year in favor of the new album.

By the time American Stars n’ Bars was released four months later, Young’s prolific songwriting nature had completely altered the album to include a side of new music “written fast and in the spirit of country music,” performed with Crazy Horse and the Saddlebags – singers Nicolette Larson and Linda Ronstadt.

Several of the still-unreleased songs from Stars n’ Bars – “Powderfinger”, “Captain Kennedy” and “Sedan Delivery” – were sent to Lynyrd Skynyrd for possible use on their Street Survivors album. None of the songs fit the tone of the album but singer Ronnie Van Zant was saving “Powderfinger” for a future LP at the time of his fatal plane crash. Van Zant and Young had sent messages of mutual admiration for each other, but Neil never got to tell the man who wrote “I hope Neil Young will remember / Southern Man don’t need him around anyhow” that “Sweet Home Alabama” was one of his favorite songs. “I’d rather play ‘Sweet Home Alabama’ than ‘Southern Man’ anytime,” Young says. “I first heard it and really liked the way they played their guitars. Then I heard my own name in it and thought, ‘Now this is pretty great….'”

In the summer of 1977, a rumor shot through California music circles that Neil Young was appearing nightly in the bars around Santa Cruz. It was disregarded by most as typical gossip, but a trip up the coast one Friday night found a crowd milling around the entrance to a small bar called the Catalyst. The marquee simply read: DUCKS. Inside, the place was filled with the dull roar of zoo people quacking and blowing duck calls. After a while, out wandered four musicians. On lead guitar was Young, his painter’s hat pulled down low. The Ducks opened with a scorching version of “Mr. Soul” and played through an hour of simple, hard Chuck Berry-esque rock & roll. The songs, only a few of which were Young’s, celebrated trucks, girls and bars. The Ducks became a secret, local institution. For a buck, you came in and Neil Young burned up the frets, then joined you at the bar for a drink.

Young had turned up in Santa Cruz to visit an old friend from the Springfield days, singer/songwriter Jeff Blackburn. Once part of the San Francisco duo Blackburn and Snow, he’d been playing around the quiet coastal town with a band that included ex-Moby Grape member Bob Mosley and drummer Johnny C. Craviotto. When the group lost its lead guitarist, Young joined up. They decided to call themselves the Ducks and within weeks every duck call within miles had been purchased.

“These guys play some great music,” Neil told one local. “Sure they want to go out and do something, but all I want to do is play some music right now, and not go out and do anything. You see, I haven’t lived in a town for eight years. I stayed on my ranch for about four years and then I just started traveling all over, never really staying anywhere. Moving into Santa Cruz is like my reemergence back into civilization. I like this town. If the situation remains cool, we can do this all summer long.”

This exchange was later written up as a front-page story in a local newspaper. Crowds began to arrive from everywhere. Record companies even sent scouts. Word got out about the house that the band lived in. There was a robbery. And one day Neil Young disappeared again.

“I still have the team spirit,” said Jeff Blackburn when I called him recently. “It’s almost hard to comprehend it ever happened. We all knew Neil had commitments and everything…. I guess we were in the fairy tale and unable to see out of it.”

After the Ducks episode, Young had taken his son Zeke for a cross-country ride in his tour bus. They ended up in Nashville and Neil decided to begin his next record there. Young rounded up a crew of sidemen that included country session musicians who had never played anything resembling rock, a singer – Nicolette Larson – he had worked with on American Stars ‘n Bars, and six acoustic guitarists. Young began his most accessible and ultimately best-selling album since Harvest. “I was feeling pretty sunny,” he recalls. Nicolette Larson had kept a tape of some of the material from when she and Neil first met and sang together at her friend Linda Ronstadt’s house. When the phone call came from Nashville, she was ready. Young barely had to show her the songs before they were singing the duets that appear on the album. The Gone with the Wind Orchestra, as the entire conglomeration of twenty-two musicians was called, lasted throughout the album and for one live performance, on Young’s thirty-second birthday, at an outdoor benefit for children’s hospitals in the Miami Beach area. Young rehearsed the outfit in a Nashville storefront and flew everyone to Florida where, sharing the windy stage with Nicolette, he played what could well have been his purest and most note-perfect performance ever. The show ended with Young playing part of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama,” which he dedicated to “a couple of friends in the sky.”

A visit to Young’s house in Zuma Beach a month later found him and Nicolette in floppy sweaters before the fireplace – Ma and Pa Kettle at home. Young made some coffee, put on the tape, and they sang with themselves while Comes a Time played. On the living-room table was the then-current issue of People, with the re-formed Crosby, Stills and Nash on the cover.

“Strange seeing that,” said Young. “Those three with Jimmy Carter on the inside… it makes me think. It’s good that they’re together, but it’s also good to be apart too. They all must feel sometimes like getting away from it. Just like when I’m someplace and decide, ‘Think I’ll get on the bus and go.’ I have to be able to go….”

Young is in Elliot Roberts’ office a year later, rubbing the two-day beard he’s grown since the end of the Rust Never Sleeps shows. The tour had ended in L.A., the night after a raging coastal fire had swept through Zuma Beach and gutted Young’s house. All that was left was the stone fireplace.

“Beautiful house,” Young says. “Burned to the ground.”

I have the impression that if the house had to go, the imagery suits Young just fine. That evening a year before, listening to Comes a Time with him an Nicolette, seems like it’s from another time and place entirely.

“People don’t understand sometimes,” he says, looking down at a pencil he’s toying with, “how I can come in and go out so fast, how I can be there and want to do something and then when it’s over, for me it’s over. To other people it’s just a beginning. Sometimes that’s hard for people to take. I can see how that would be. I just don’t like to stay in one place very long. I move around, I keep doing different things….” He looks up. “Just different things.”

It must be difficult, I wonder, to decide which impulses to follow.

“I only follow the ones I get,” says Young. “And if it makes me laugh… I know it’s a good one. Basically I’ve had a really good time, even though my songs have mostly expressed the down side. I like that there’s a lot of humor in rock & roll now. A lot of people take me so seriously. They don’t know what to do with me not taking myself so seriously anymore. I guess it’s just that a lot of people from the Sixties and early Seventies…” the old smirk… “just aren’t that funny.”

To many of his own fans Neil Young is still the antithesis of humor. He is the dishelved loner, a space case, a drug casualty….

“Two times I’ve had to call Neil with reports of his death,” says Roberts. “One time his father called me. Said that he’d read in the AP that Neil died and was it true. Another time Warner Bros. called me and said was there any truth to Neil’s demise in Paris. Both times they were ‘drug accidents.'” “Right,” says Young. “I was traveling on the highway and was hit by a huge drug truck.”

One of Young’s long-standing jokes is that he’s saving his best material for his “Bus Crash” album. The few who have heard samplings of Young’s tape vaults – songs that didn’t fit into the flow of his albums, entire unreleased works, live tapes, Buffalo Springfield tapes – agree that some of his most compelling performances are among the unreleased material.

“All those songs,” he says, “they’re still there. They’re there. And they’re in an order. They’re not gone. But, you know, they’re old songs. Who wants to hear about it. They’re depressing. They are. It’s like ancient history to me. I don’t want to have to deal with that stuff coming out.”

“Until,” I ask, “you’re not around to deal with them coming out?”

“That’s right,” he says. “Then they’re there. I think every artist plans for the future like that. I have things in a certain order, so that if anything ever happened to me it would be pretty evident what to do.”

A few days later, photographer Joel Bernstein and I are to meet Young and his new wife Pegi at Elliot Roberts’ home in the wilds of northern California. The screen door opens and a disturbed-looking, wild-eyed Neil Young bolts in.

“Did you read,” he all but hisses, “that article in Time magazine about me and Bob Dylan. I’d like to make a comment about that.”

The Time writer had caught both Young’s and Dylan’s shows when they recently played Madison Square Garden back to back, and compared the artists according to their most current tours. The verdict was that Dylan had slipped into the billow sleeves of middle age and now “sometimes looks as if he is auditioning for the Gong Show.” Young, on the other hand, “kept closer to the ground than Dylan and sneaked into rock’s pantheon like a highwayman.”

“Show me this pantheon,” says Neil Young, pacing around his neighbor’s kitchen, insulted that he could be pitted against his own mentor. “I don’t want to have to read that shit in Time magazine. That’s irresponsible journalism. Disco attitude. Somebody somewhere is going to believe it. I did not see Dylan’s show – but to think that all he’s given, all he’s meant to us… you can’t cancel that in one night…. I don’t know how to feel.” He sits down at a table, clasping his hands. “I don’t think I want to comment at all.”

We talk of other things during the night, but the Time article seems to run through all of Young’s thoughts. To him it represents another wave of popularity, the kind that wrenched everything out of control for him before. I remind him of something he once told Peter Frampton, after meeting the English guitarist in New York when Frampton was suffering his own critical drubbing. It is the mystique that gets written about, not the music. “Well,” says Young, staring strangely at the tape recorder whirring a few feet away from him, “as soon as you start talking about mystique, you have none.”

I knew then what would happen.

A few days later Young would call and ask that this article not be published. It had happened before. It had happened after the ROLLING STONE interview in 1975, but I had gone out of town to write the article and missed the nervous messages. It had happened after the Stills and Young tour when Young called to say he’d “been thinking a lot about maybe not having an article come out” and it happened after the 1976 tour when “the time wasn’t right.” It is hard to argue with a man whose emotions have served him so well.

“I’ve got a job to do,” Young had said at his ranch. “The Eighties are here. I’ve got to just tear down whatever has happened to me and build something new. You can only have it for so long before you don’t have it anymore. You become an old-timer… which… I could be… I don’t know.

“After all, it’s just me and Frank Sinatra left on Reprise Records.”

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #284 – Cameron Crowe – February 8, 1979