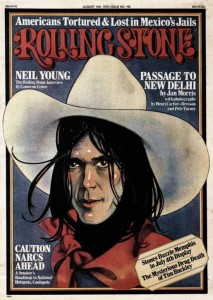

Rolling Stone #193: Neil Young

So Hard to Make Arrangements For Yourself:

The Rolling Stone Interview with Neil Young

“An interview with Neil Young was the holy grail in 1975. It’s still a rare occasion 25 years later. I was nervous as hell.”

– Cameron Crowe – Summer 2000

Nearing 30, Neil Young is the most enigmatic of all the superstars to emerge from Buffalo Springfield and Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. His often cryptic studies of lonely desperation and shaky-voiced antiheroics have led many to brand him a loner and a recluse. Harvest was the last time that he struck the delicate balance between critical and commercial acceptance, and his subsequent albums have grown increasingly inaccessible to a mass audience.

Young’s first comprehensive interview comes at a seeming turning point in his life and career. After an amicable breakup with actress Carrie Snodgrass, he’s moved from his Northern California ranch to the relative hustle and bustle of Malibu. In the words of a close friend, he seems “frisky…in an incredible mood.” Young has unwound to the point where he can approach a story about his career as potentially “a lot of fun.”

The interview was held while cruising down Sunset Boulevard in a rented red Mercedes and on the back porch of his Malibu beach house. Cooperative throughout, Young only made a single request: “Just keep one thing in mind,” he said as soon as the tape recorder had been turned off for the first time. “I may remember it all differently tomorrow.”

Why is it that you’ve finally decided to talk now? For the past five years journalists requesting Neil Young interviews were told you had nothing to say.

There’s a lot I have to say. I never did interviews because they always got me in trouble. Always. They never came out right. I just don’t like them. As a matter of fact, the more I didn’t do them the more they wanted them; the more I said by not saying anything. But things change, you know. I feel very free now. I don’t have an old lady anymore. I relate it a lot to that. I’m back living in Southern California. I feel more open than I have in a long while. I’m coming out and speaking to a lot of people. I feel like something new is happening in my life.

I’m really turned on by the new music I’m making now, back with Crazy Horse. Today, even as I’m talking, the songs are running through my head. I’m excited. I think everything I’ve done is valid or else I wouldn’t have released it, but I do realize the last three albums have been a certain way. I know I’ve gotten a lot of bad publicity for them. Somehow I feel like I’ve surfaced out of some kind of murk. And the proof will be in my next album. Tonight’s the Night, I would say is the last chapter of a period I went through.

Why the murky period?

Oh, I don’t know. Danny’s death probably tripped it off. [Danny Whitten, leader of Crazy Horse and Young’s rhythm guitarist/second vocalist.] It happened right before the Time Fades Away tour. He was supposed to be in the group. We [Ben Keith, steel guitar; Jack Nitzche, piano; Tim Drummond, bass; Kenny Buttrey, drums; and Young] were rehearsing with him and he just couldn’t cut it. He couldn’t remember anything. He was too out of it. Too far gone. I had to tell him to go back to L.A. “It’s not happening, man. You’re not together enough.” He just said, “I’ve got nowhere else to go, man. How am I gonna tell my friends?” And he split. That night the coroner called me from L.A. and told me he’d ODed. That blew my mind. Fucking blew my mind. I loved Danny. I felt responsible. And from there, I had to go right out on this huge tour of huge arenas. I was very nervous and …insecure.

Why, then, did you release a live album?

I thought it was valid. Time Fades Away was a very nervous album. And that’s exactly where I was at on the tour. If you ever sat down and listened to all my records, there’s been a place for it in there. Not that you’d go there every time you wanted to enjoy some music, but if you’re on the trip it’s important. Every one of my records, to me, is like an ongoing autobiography. I can’t write the same book every time. There are artists that can. They put out three or four albums every year and everything fucking sounds the same. That’s great. Somebody’s trying to communicate to a lot of people and give them the kind of music that they know they want to hear. That isn’t my trip. My trip is to express what’s on my mind. I don’t expect people to listen to my music all the time. Sometimes it’s too intense. If you’re gonna put a record on at 11:00 in the morning, don’t put on Tonight’s the Night. Put on the Doobie Brothers.

Time Fades Away, as the followup to Harvest, could have been a huge album…

If it had been commercial.

As it is, it’s one of your least selling solo albums. Did you realize what you were sacrificing at the time?

I probably did. I imagine I could have come up with the perfect followup album. A real winner. But it would have been something that everybody was expecting. And when it got there they would have thought that they understood what I was all about and that would have been it for me. I would have painted myself in the corner. The fact is I’m not that lone, laid-back figure with a guitar. I’m just not that way anymore. I don’t want to feel like people expect me to be a certain way. Nobody expected Time Fades Away and I’m not sorry I put it out. I didn’t need the money, I didn’t need the fame. You gotta keep changing. Shirts, old ladies, whatever. I’d rather keep changing and lose a lot of people along the way. If that’s the price, I’ll pay it. I don’t give a shit if my audience is a hundred or a hundred million. It doesn’t make any difference to me. I’m convinced that what sells and what I do are two completely different things. If they meet, it’s coincidence. I just appreciate the freedom to put out an album like Tonight’s the Night if I want to.

You sound pretty drunk on that album.

I would have to say that’s the most liquid album I’ve ever made [laughs]. You almost need a life preserver to get through that one. We were all leaning on the ol’ cactus…and, again, I think that it’s something people should hear. They should hear what the artist sounds like under all circumstances if they want to get a complete portrait. Everybody gets fucked up, man. Everybody gets fucked up sooner or later. You’re just pretending if you don’t let your music get just as liquid as you are when you’re really high.

Is that the point of the album?

No. No. That’s the means to an end. The whole thing is about life, dope and death. When we [Nils Lofgren, guitars and piano, Talbot, Molina and Young] played that music we were all thinking of Danny Whitten and Bruce Berry, two close members of our unit lost to junk overdoses. The Tonight’s the Night sessions were the first time what was left of Crazy Horse had gotten together since Danny died. It was up to us to get the strength together among us to fill the hole he left. The other OD, Bruce Berry, was CSNY’s roadie for a long time. His brother Ken runs Studio Instrument Rentals, where we recorded the album. So we had a lot of vibes going for us. There was a lot of spirit in the music we made. It’s funny, I remember the whole experience in black and white. We’d go down to S.I.R. about 5:00 in the afternoon and start getting high, drinking tequila and playing pool. About midnight, we’d start playing. And we played Bruce and Danny on their way all through the night. I’m not a junkie and I won’t even try it out to check out what it’s like…but we all got high enough, right out there on the edge where we felt wide open to the whole mood. It was spooky. I probably feel this album more than anything else I’ve ever done.

Why did you wait until now to release Tonight’s the Night? Isn’t it almost two years old?

I never finished it. I only had nine songs, so I set the whole thing aside and did On the Beach instead. It took Elliot [manager Elliot Roberts] to finish Tonight’s the Night. You see, awhile back there were some people who were gonna make a Broadway show out of the story of Bruce Berry and everything. They even had a script written. We were putting together a tape for them and in the process of listening back on the old tracks, Elliot found three even older songs that related to the trip, “Lookout Joe,” “Borrowed Tune” and “Come On Baby Let’s Go Downtown,” a live track from when I played the Fillmore East with Crazy Horse. Danny even sings lead on that one. Elliot added those songs to the original nine and sequenced them all into a cohesive story. But I still had no plans whatsoever to release it. I already had another new album called Homegrown in the can. The cover was finished and everything. [laughs] Ah, but they’ll never hear that one.

Okay. Why not?

I’ll tell you the whole story. I had a playback party for Homegrown for me and about ten friends. We were out of our minds. We all listened to the album and Tonight’s the Night happened to be on the same reel. So we listened to that too, just for laughs. No comparison.

So you released Tonight’s the Night. Just like that?

Not because Homegrown wasn’t as good. A lot of people would probably say it’s better. I know the first time I listened back on Tonight’s the Night it was one of the most out-of-tune things I’d ever heard. Everyone’s off-key. I couldn’t hack it. But by listening to those two albums back to back at the party, I started to see the weaknesses in Homegrown. I took Tonight’s the Night because of its overall strength in performance and feeling. The theme may be a little depressing, but the general feeling is much more elevating than Homegrown. Putting this album out is almost an experiment. I fully expect some of the most determinedly worst reviews I’ve ever had. I mean if anybody really wanted to let go, they could do it on this one. And undoubtedly a few people will. That’s good for them, though. I like to see people make giant breakthroughs for themselves. It’s good for their psyche to get it all off their chests. [laughs] I’ve seen Tonight’s the Night draw a line everywhere it’s been played. People who thought they would never dislike anything I did fall on the other side of the line. Others who thought “I can’t listen to that cat. He’s just too sad,” or whatever…”His voice is funny.” They listen another way now. I’m sure parts of Homegrown will surface on other albums of mine. There’s some beautiful stuff that Emmylou Harris sings harmony on. I don’t know. That record might be more what people would rather hear from me now, but it was just a very down album. It was the darker side to Harvest. A lot of the songs had to do with me breaking up with my old lady. It was a little too personal…it scared me. Plus, I had just released On the Beach, probably one the most depressing records I’ve ever made. I don’t want to get down to the point where I can’t even get up. I mean there’s something to going down there and looking around, but I don’t know about sticking around.

You didn’t come from a musical family…

Well, my father played a little ukulele. [laughs] It just happened. I felt it. I couldn’t stop thinking about it. All of a sudden I wanted a guitar and that was it. I started playing around the Winnipeg community clubs, high school dances. I played as much as I could.

With a band?

Oh yeah, always with a band. I never tried it solo until I was 19. Eighteen or 19.

Were you writing at the time?

I started off writing instrumentals. Words came much later. My idol at the time was Hank B. Marvin, Cliff Richard’s guitar player in the Shadows. He was the hero of all the guitar players around Winnipeg at the time. Randy Bachman too; he was around then, playing the same circuit. He had a great sound. Used to use a tape repeat.

When did you start singing?

I remember singing Beatles tunes…the first song I ever sang in front of people was “It Won’t Be Long” and then “Money (That’s What I Want).” That was in the Calvin High School Cafeteria. My big moment.

How much different from the States was growing up in Canada?

Everybody in Canada wants to get to the States. At least they did then. I couldn’t wait to get out of there because I knew my only chance to be heard was in the States. But I couldn’t get down there without a working permit, and I didn’t have one. So eventually I just came down illegally and it took until 1970 for me to get a green card. I worked illegally during all of the Buffalo Springfield and of Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. I didn’t have any papers. I couldn’t get a card because I would be replacing an American musician in the Union. You had to be real well known and irreplaceable and a separate entity by yourself. So I got the card after I got that kind of stature – which you can’t get without fucking being here…the whole thing is ridiculous. The only way to get in is to be here. You can’t be here unless it’s all right for you to be here. So fuck it. It’s like ‘throw the witch in the water and if it drowns it wasn’t a witch. If it comes up, it is a witch and then you kill it.’ Same logic. But we finally got it together.

Did you know Joni Mitchell in those days?

I’ve known Joni since I was 18. I met her in one of the coffeehouses. She was beautiful. That was my first impression. She was real frail and wispy looking. And her cheekbones were so beautifully shaped. She’d always wear light satins and silks. I remember thinking that if you blew hard enough, you could probably knock her over. She could hold up a Martin D18 pretty well, though. What an incredible talent she is. She writes about her relationships so much more vividly than I do. I use…I guess I put more of a veil over what I’m talking about. I’ve written a few songs that were as stark as hers. Songs like “Pardon My Heart,” “Home Fires,” “Love Art Blues”…almost all of Homegrown. I’ve never released any of those. And I probably never will. I think I’d be too embarrassed to put them out. They’re a little too real.

How do you look back on the whole Buffalo Springfield experience?

Great experience. Those were really good days. Great people. Everybody in that group was a fucking genius at what they did. That was a great group, man. There’ll never be another Buffalo Springfield. Never. Everybody’s gone such separate ways now, I don’t know. If everybody showed up in one place at one time with all the amps and everything, I’d love it. But I’d sure as hell hate to have to get it together. I’d love to play with that band again, just to see if the buzz was still there.

There’s a few stock Springfield myths I should ask you about. How about the old hearse story?

True. Bruce and I were tooling around L.A. in my hearse. I loved the hearse. Six people could be getting high in the front and back and nobody would be able to see in because of the curtains. The heater was great. And the tray…the tray was dynamite. You open the side door and the tray whips right out onto the sidewalk. What could be cooler than that? What a way to make your entrance. Pull up to a gig and just wheel out all your stuff on the tray. Anyway, Bruce and I were taking in California. The Promised Land. We were heading up to San Francisco. Stephen and Richie Furay, who were in town putting together a band, just happened to be driving around too. Stephen had met me before and remembered I had a hearse. As soon as he saw the Ontario plates, he knew it was me. So they stopped us. I was happy to see fucking anybody I knew. And it seemed very logical to us that we form a band. We picked up Dewey Martin for the drums, which was my idea, four or five days later. Stephen was really pulling for Billy Munday at the time. He’d say ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah. Dewey’s good, but Jesus…he talks too fucking much.’ I was right though. Dewey was fucking good.

How much has the friction between you and Stills been beneficial over the years?

I think people really have that friction business out of hand. Stephen and I just play really good together. People can’t comprehend that we both can play lead guitar in the band and not fight over it. We have total respect for musicianship and we both bring out the perfectionist in each other. We both enjoy that. It’s part of doing what we do. In that respect being at loggerheads has worked to our advantage. Stephen Stills and I have made some incredible music with each other. Especially in the Springfield. We were young. We had a lot of energy.

Why did you leave the band?

I just couldn’t handle it toward the end. My nerves couldn’t handle the trip. It wasn’t me scheming on a solo career, it wasn’t anything but my nerves. Everything started to go too fucking fast, I can tell that now. I was going crazy, you know, joining and quitting and joining again. I began to feel like I didn’t have to answer or obey anyone. I need more space. That was a big problem in my head. So I’d quit, then I’d come back ’cause it sounded so good. It was a constant problem. I just wasn’t mature enough to deal with it. I was very young. We were getting the shaft from every angle and it seemed like we were trying to make it so bad and were getting nowhere. The following we had in the beginning, and those people know who they are, was a real special thing. It gave all of us, I think, the strength to do what we’ve done. With the intensity that we’ve been able to do it. Those few people who were there in the very beginning.

Last Springfield question. Are there, in fact, several albums of unreleased material?

I’ve got all of that. I’ve got those tapes.

Why have you sat on them for so long? What are you waiting for?

I’ll wait until I hear from some of the other guys. See if anybody else has any tapes. I don’t know if Richie or Dicky Davis [Springfield road manager] has anything. I’ve got good stuff. Great songs. “My Kind of Love,” “My Angel,” “Down to the Wire,” “Baby Don’t Scold Me.” We’ll see what happens.

What was your life like after the Springfield?

It was all right. I needed to get out to the sticks for a while and just relax. I headed for Topanga Canyon and got myself together. I bought house that overlooked the whole canyon. I eventually got out of that house because I couldn’t handle all the people who kept coming up all the time. Sure was a comfortable fucking place…that was ’69, about when I started living with my first wife, Susan. Beautiful woman.

Was your first solo album a love song for her?

No. Very few of my albums are love songs to anyone. Music is so big, man, it just takes up a lot of room. I’ve dedicated my life to my music so far. And every time I’ve let it slip and gotten somewhere else it showed. Music lasts…a lot longer than relationships do. My first album was very much a first album. I wanted to prove to myself that I could do it. And I did, thanks the wonder of modern machinery. That first album was overdub city. It’s still one of my favorites though. Everybody Knows This is Nowhere is probably my best. It’s my favorite one. I’ve always loved Crazy Horse from the first time I heard the Rockets album on White Whale. The original band we had in ’69 and ’70 – Molina, Talbot, Whitten and me. That was wonderful. And it’s back that way again now. Everything I’ve ever done with Crazy Horse had been incredible. Just for the feeling, if nothing else.

Why did you join CSNY, then? You were already working steadily with Crazy Horse.

Stephen. I love playing with the other guys, but playing with Stephen is special. David an excellent rhythm guitarist and Graham sings so great…shit, I don’t have to tell anybody those guys are phenomenal. I knew it would be fun. I didn’t have to be out front. I could lay back. It didn’t have to be me all the time. They were a big group and it was easy for me. I could still work double time with Crazy Horse. With CSNY, I was basically just an instrumentalist that sang a couple of songs with them. And the music was great. CSNY, I think, has always been a lot bigger thing to everybody else than it is to us. People always refer to me as Neil Young of CSNY, right? It’s not my main trip. It’s something that I do every once in a while. I’ve constantly been working on my own trip all along. And now that Crazy Horse is back in shape, I’m even more self-motivated.

How much of your own solo success, though, was due to CSNY?

For sure CSNY put my name out there. They gave me a lot of publicity. But, in all modesty, After the Gold Rush, which was kind of the turning point, was a strong album. I really think it was. A lot of hard work went into it. Everything was there. The picture it painted was a strong one. After the Gold Rush was the spirit of Topanga Canyon. It seemed like I realized that I’d gotten somewhere. I joined CSNY and was still working a lot with Crazy Horse…I was playing all the time. And having a great time. Right after that album, I left the house. It was a good coda.

How did you cope with your first real blast of superstardom after that?

The first thing I did was a long tour of small halls. Just me and a guitar. I loved it. It was real personal. Very much a one-on-one thing with the crowd. It was later, after Harvest, that I hid myself away. I tried to stay away from it all. I thought the record [Harvest] was good, but I also knew that something else was dying. I became very reclusive. I didn’t want to come out much.

Why? Were you depressed? Scared?

I think I was pretty happy. In spite of everything, I had my old lady moved to the ranch. A lot of it was my back. I was in and out of hospitals for the two years between After the Gold Rush and Harvest. I have one weak side all the muscles slipped on me. My discs slipped. I couldn’t hold my guitar up. That’s why I sat down on my whole solo tour. I couldn’t move around too well, so I laid low for a long time on the ranch and just didn’t have any contact, you know. I wore a brace. Crosby would come up to see how I was, we’d got for a walk and it took me 45 minutes to get to the studio, which is only 400 yards from the house. I could only stand up four hours a day. I recorded most of Harvest in that brace. That’s a lot of the reason it’s such a mellow album. I couldn’t physically play an electric guitar. “Are You Ready for the Country,” “Alabama” and “Words” were all done after I had the operation. The doctors were starting to talk about wheelchairs and shit, so I had some discs removed. But for the most part, I spent two years flat on my back. I had a lot of time to think about what had happened to me.

Have you ever been in analysis?

You mean have I ever been to a psychiatrist? [laughs] No. They’re all real interested in me though. They always ask a lot of questions when I’m around them.

What do they ask?

Well, I had some seizures. They used to ask me a lot of questions about how I felt, stuff like that. I told them all the thoughts I had and the images I see if I, you know, faint or fall down or something. That’s not real important though.

Do you still have seizures?

Yeah, I still do. I wish I didn’t. I thought I had it licked.

Is it a physical or mental…

I don’t know. Epilepsy is something nobody knows much about. It’s just part of me. Part of my head, part of what’s happening in there. Sometimes something in my brain triggers it off. Sometimes when I get really high it’s a very psychedelic experience to have a seizure. You slip into some other world. Your body’s flapping around and you’re biting your tongue and batting your head on the ground but your mind is off somewhere else. The only scary thing about it is not going or being there, it’s realizing you’re totally comfortable in this…void. And that shocks you back into reality. It’s a very disorienting experience. It’s difficult to get a grip on yourself. The last time it happened, it took about an hour-and-a-half of just walking around the ranch with two of my friends to get it together.

Has it ever happened onstage?

No. Never has. I felt like it was a couple times and I’ve always left the stage. I get too high or something. It’s just pressure from around, you know. That’s why I don’t like crowds too much.

What were the sessions like for Deja Vu? Was it a band effort?

The band sessions on that record were “Helpless,” “Woodstock” and “Almost Cut My Hair.” That was Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. All the other ones were combinations, records that were more done by one person using the other people. “Woodstock” was a great record at first. It was a great live record, man. Everyone played and sang at once. Stephen sang the shit out of it. The track was magic. Then, later on, they were in the studio for a long time and started nitpicking. Sure enough, Stephen erased the vocal and put another one on that wasn’t nearly as incredible. They did a lot of things over again that I thought were more raw and vital sounding. But that’s all personal taste. I’m only saying that because it might be interesting to some people how we put that album together. I’m very happy with every one of the things I’ve recorded with them. They turned out really fine. I certainly don’t hold any grudges.

You seem a bit defensive.

Well, everybody always concentrates on this whole thing that we fight all the time among each other. That’s a load of shit. They don’t know what the fuck they’re talking about. It’s all rumors. When the four of us are together it’s real intense. When you’re dealing with any four totally different people who all have ideas on how to do one thing, it gets steamy. And we love it, man. We’re having a great time. People make up so much shit, though. I’ve read so much gossip in Rolling Stone alone…Ann Landers would blanch. It would surprise you. Somehow we’ve gotten on this social-register level and it has nothing to do with what we’re trying to put out. The music press writes the weirdest shit about us. They’re just wasting their fucking time.

There was recent item published that CSNY had tried to record a new album but couldn’t because you felt ‘someplace else.’

Total bullshit. That’s just somebody trying to come up with a good line and stick it in my mouth. ‘Yeah, that’s kind of ethereal. Sounds like something Neil Young might say.’ And bingo…it’s like they were there. We had some recording sessions, you know, and we recorded a few things. That’s what happened. We went down to the Record Plant in Sausalito, rented some studio time and left with two things in the can.

What was that?

A song of David’s and a song of Graham’s that were great. We were really into something nice. But a lot of things were happening at the same time. Crosby’s baby was about to be born. Some of us wanted to rest for a while. We’d been working very hard. Everybody has a different viewpoint and it just takes us a while to get them all together. It’s a great group for that, though. I’m sure there’ll come a time when we’ll do something again. We really did accomplish some things at those sessions. And just because the sessions only lasted three days, people started building up bullshit stories. We all love each other, but we’re into another period where we’re all hot on our own projects. Stephen’s on tour with his new album, Graham and David are recording and I’m into my new album with Crazy Horse. Looking back, we might have been wiser to do the album before the tour. While we were still building the energy. But there’s other times to record. Atlantic still has CSNY. Whenever we record together, we do it for Ahmet, which I think is right. Ahmet Ertegun kept the Buffalo Springfield afloat for as along as it was. He’s always been great. I love him. There may be a live album to come from the tour last summer too. I know there at least 25 minutes of my songs that are definitely releasable. We’ve got some really good stuff in the can for that tour. There was some good playing.

Why did you travel totally separate from everyone else on that tour?

I wanted to stay totally separate from everything, except the music. It worked well. I left right after every gig with my kid, my dog and two friends. I’d be very refreshed and feeling great for every show.

Why did you make a movie?

It was something that I wanted to do. The music, which has been and always will be my primary thing, just seemed to point that way. I wanted to express a visual picture of what I was singing about.

One critic wrote that the movie’s theme was ‘life if pointless.’

Maybe that’s what the guy got out of it. I just made a feeling. It’s hard to say what the movie means. I think it’s a good film for a first film. I think it’s a really good film. I don’t think I was trying to say that life is pointless. It does lay a lot of shit on people though. It wasn’t made for entertainment. I’ll admit, I made it for myself. Whatever it is, that’s the way I felt. I made it for me. I never even had a script.

Did the bad reviews surprise you at all?

Of course not. The film community doesn’t want to see me in there. What do they want with Journey through the Past? [laughs] It’s got no plot. No point. No stars. They don’t want to see that. But the next time, man, we’ll get them. The next time. I’ve got all the equipment, all the ideas and motivation to make another picture. I’ve even been keeping my chops up as a cameraman by being on hire under the name of Bernard Shakey. I filmed a Hyatt House commercial not too long ago. I’m set. [laughs] I’m just waiting for the right time.

What about a plot?

It’s real simple. Maybe it’s not a plot but it’s a very strong feeling. It’s built around three or four people living together. No music. I’ll never make another movie what has anything to do with me. I’ll tell you that. That was the only way I could get to do the first movie. I wanted to be in a movie, so I did it. I sacrificed myself as a musician to do it.

So you don’t really consider the soundtrack album an official Neil Young release?

No. There was an unfortunate sequence of events surrounding Journey to the Past. The record company told me that they’d finance me doing the movie only if I gave them the soundtrack album. They took the thing [the soundtrack] and put it right out. Then they told me that they didn’t want to release the movie because it wasn’t…well, they wanted to group it with a bunch of other films. I wanted to get it out there on its own. So they chickened out on the movie because they thought it was weird. But they took me for the album. That’s always been a ticklish subject with me. That’s the only instance of discooperation and confusion that I’ve ever had with Warners. Somebody really missed the boat on that one. They fucked me up for sure. It’s all right though. We found another distributor. It paid for itself. Even though it got banned in England, you know. They thought it was immoral. There were swearing and references to Christ that didn’t sell well with them.

Why did you leave the ranch?

It just got to be too big of a trip. There was too much going on the last couple of years. None of it had anything to do with music. I just had too many fucking people hanging around who don’t really know me. They were parasites whether they intended to be or not. They lived off me, used my money to buy things, used my telephone to make their calls. General leeching. It hurt my feelings a lot when I reached that realization. I didn’t want to believe I was being taken advantage of. I didn’t like having to be boss and I don’t like having to say ‘Get the fuck out.’ That’s why I have different houses now. When people gather around me, I just split now. I mean my ranch is more beautiful and lasting than ever. It’s strong without me. I just don’t feel like it’s the only place I can be and be safe anymore. I feel much stronger now.

Have you got a name for the new album?

I think I’ll call it My Old Neighborhood. Either that or Ride my Llama. It’s weird, I’ve got all these songs about Peru, the Aztecs and the Incas. Time travel stuff. We’ve got one song called “Marlon Brando, John Ehrlichman, Pocahontas and Me”. I’m playing a lot of electric guitar and that’s what I like best. Two guitars, bass and drums. And it’s really flying off the ground too. Fucking unbelievable. I’ve got a bet with Elliot and it’ll be out before the end of September. After that we’ll probably go out on a fall tour of 3000 seaters. Me and Crazy Horse again. I couldn’t be happier. That, combined with the bachelor life…I feel magnificent. Now is the first time I can remember coming out of a relationship, definitely not wanting to get into another one. I’m just not looking. I’m so happy with the space I’m in right now. It’s like spring. [laughs] I’ll sell you two bottles of it for $1.50.

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #193 – Cameron Crowe – August 14, 1975