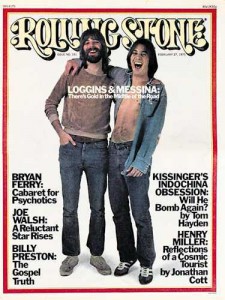

Rolling Stone #181: Joe Walsh

Joe Walsh, Child of the Silent Majority: Ex-James Gangster Tends His Garden

The gold records for Rides Again, Thirds, James Gang Live and The Smoker You Drink, The Player You Get are stashed in the master bedroom. There are no stray guitars, cases or rock & roll memorabilia strewn about the living room; every thing’s been neatly stored in a well-hidden in-house recording studio. For visitors to Joe Walsh’s pleasantly conservative Studio City home, there is only a shag-carpeted solidly middle-class motif that does little to betray the profession of its resident.

It’s been almost sever years since the 27 year old Walsh left behind the quiet solitude of Boulder, Colorado, for the career practicality of Los Angeles. For one who has consistently managed–most notably by leaving the James Gang at their late ’71 peak–either to dodge or postpone superstardom, Walsh’s move was a major concession to his ever mounting popularity.

“I guess I’m still a little afraid of it all,” he admitted, slouching at a desk in his small, wood-finished den. A few days away from finally completing the follow-up to The Smoker (released in June 1973), Walsh seemed struck with a touch of stage fright. It was late–about three in the morning–and the hushed serenity of an empty house bred introspection.

“I know this album’s going to be an important one for me, but it’s not easy to just crank them out anymore, I’ve got, what, six or seven albums out. I don’t want the next album to sound like a bunch of outtakes from Smoker. I want it to be the difference between Revolver and Sgt. Pepper. I’ve held back until that development was there, even though the record company’s been screaming for it. I want it to be a big, big step…in thoughts, vocals, playing and maturity.

Two months later, the new album entitled So What was done, out and gold. Walsh had also produced an album for Dan Fogelberg. As we met for another talk in his den, Walsh seemed to be at another crossroads. “There are two ways I could go with my career right now,” he said. “It’s my decision. I could go out and play all the really huge places and make tons of bucks…but if that’s what I wanted to do, I would have stuck with the James Gang. I’ve already ‘made it’ to whatever degree I ever wanted to. I’d rather lay back a bit right now. The album’s finished, and I’d rather let people listen to it for a while.

“I’m getting more and more into producing, too. After watching Bill Szymczyk produce me for so long, I’ve learned a lot. Danny’s album was a joy. I love producing. To me, it’s just as important as my recording career right now,” As for the tour, which began in late January:” I’m going to stay away from the huge arenas. Just put me in a comfortable-sized hall and I’ll be happy.”

Born in New York and raised n New Jersey, Joe Walsh possesses a certain built-in anonymity that is reminiscent of, say, the young mechanic down the street. His sandy blond hair and universal features make him something less than the archetypal rock & roll specimen. He is not displeased with the distinction. “I was the All-American boy,” he said, “a child of the silent majority, a third-chair clarinet in my junior high school band.” He gleefully recalled his public debut. He played a rhythm guitar in an eight grade talent show with a friend, Bob Ortman; they performed “Exodus,” using a Wollensack tape recorder as a PA system.

“We sounded like Hank Williams sitting on a vibrator,” said Walsh, cracking up at the memory and punctuating himself with his favorite expression: “It was tre-men-dous!”

These days, Walsh stands surely among rock & roll’s finest guitarists. Ask Jimmy Page about Joe, and he will say, “He has a tremendous feel for the instrument. I’ve loved his style since the early James Gang.” Or Eric Clapton: “He’s one of the best guitarists to surface in some time. I don’t listen to many records, but I listen to his.” Or Pete Townshend: “Joe Walsh is a fluid and intelligent player. There’re not many like that around.”

In the beginning, though, Walsh stuck with rhythm guitar; in high school, he formed another duo with another schoolmate, Bob Edwards, and they called themselves the G-Clefts. “Even though we could hardly play anything, we had plans to be the next Ventures. All those great instrumentals like ‘Wipe Out,’ ‘Wild Weekend’ and ‘Walk, Don’t Run,’ were coming out, and we learned them all. We were terrible; but it was cool. I never got any shit ’cause I only played rhythm.”

Walsh never got serious about music, he said, until the Beatles broke in 1964. “I took one look on the Ed Sullivan Show and it was, ‘Fuck school. This makes it!” I memorized every Beatles song and went to Shea Stadium and screamed right along with all those chicks.”

He dissolved the G-Clefts and signed up with the nearest thing to Liverpool he could find in New Jersey, a band called the Nomads. “They had just dumped their bass player and asked me if I could play. I said ‘sure/’ I never played bass n my life, but I figured it couldn’t be to hard with only four strings. I ended up playing bass for the Nomads most of my senior year. My parents still have a picture of me all slicked up, with a collarless Beatles jacket and Beatles boots, playing at the prom.”

The dream was soon to evaporate: It was time for the All-American boy to go to college. “I fought with my parents, tried to tell them, ‘Look, I’m a rock star here. I’m gonna be a Beatle. This is really important.’ And they said, ‘Baloney, you’re going to college.’ So I went.”

Walsh applied and was accepted into a number of small Midwestern schools and decided at the last minute–and for no particular reason–to enroll in Kent State. It was fall of 1965 and Kent State was–well, as Walsh recalled: “Playboy called it a country club, ’cause you didn’t have to study to pass…so Kent sounded fine to me.” He packed some books, clothes, and “just in case”–a Vox amp and a Rickenbacher 12 string–and entered college.

He lasted one quarter, ending up with a 1.8 grade-point average. He stuck around Kent, though, looking for a band. “There was a tremendous scene at Kent. I really got into it. Everybody went down to the local clubs, drank 3.2 beer, played Sam the Sham records and got in fights.” Joe finally found a juke-box band in need of a lead guitar. The group, called the Measles, soon became Kent’s hottest act, and Walsh, at 18, was their star. he moved into a condemned farmhouse on the edge of town and began an idyllic three years of freedom. It was, he now recalls, one of the happiest times of his life.

“I even wish now that I could play somewhere four sets a night, a couple nights a week, ’cause that’s when you’re at your best.” Joe raked his fingers through his hair and shook his head. In an instant, one realized that he was here in body only. “We were really close with the audiences,” he said. “We’d goof around, sing ‘Happy Birthday’ to people, bring the police onstage to sing ‘Little Black Egg.’ Everybody was a part of a happy family. It was a secure, beautiful time.

But Kent’s beer party atmosphere soon gave way to bad dope; students grew angry over the war. City authorities forced Walsh out of his farmhouse, and one of the Measles joined the Army. Walsh split the band. He soon heard from another successful dance band from Cleveland, the James Gang; they had just lost their lead guitarist (Glenn Schwartz) to Pacific Gas and Electric. “They had heard I was hot stuff.” said Walsh, “so they asked me to join. I had some big shoes to fill; I began to study the guitar like mad, buying records and reading all I could. I wasn’t even aware of B.B. King until I read an interview with Eric Clapton where he talked about stealing his licks. I had a lot of catching up to do. After a while, I started to branch out and write my own music. And Walsh began to use what he calls his “Duane Eddy throat.”

“I really didn’t want to sing,” he said, “but Fox made me, and I went along. I’ve always been self-conscious of my voice. Not that it’s good or bad; it’s just…different”

With the help of staff producer Bill Szymczyk, the James Gang signed a contract with ABC/Bluesway, cut an album, Yer Album, and later, under management by Cleveland promoter Mike Belkin, began to build a reputation based on endless touring with a high energy stage show. Shortly before the release of Rides Again, the James Gang opened a show for the Who in Pittsburgh. Townshend caught the Gang and was impressed enough to invite them on the Who’s subsequent European tour.

“He really identified with what we were doing,” said Walsh. “Pete’s a very melodic player and so am I. He told me that he appreciated my playing. I was flattered beyond belief because I didn’t think I was that good. Pete and I really hit it off. We had the same frustrations about working with a three-piece group.

“The next thing I knew, he was saying in interviews that he had heard ‘this great guitar player from the James Gang’ and that he was America’s answer to all the English flash guitarists. Then, right on the heels of all this, we put out our best album, Rides Again. The word got out and we started to get gigs from everywhere. That was the high point of my stay with the James Gang.”

The downhill slide was soon to follow. “The songs I was writing,” Walsh explained, “needed more texture than a trio could offer. I was writing with harmony and nobody could sing them; I was writing for piano and we couldn’t play one onstage. I was frustrated. I had just written and recorded “The Bomber” and “Tend My Garden” and couldn’t really re-create them onstage. Townshend had finished Tommy and was going through the same changes. We got along so well that I gave him the fat orange Gretsch guitar that he used on Who’s Next and Clapton’s Rainbow Concert.”

Not long after meeting Townshend, Walsh returned from a road trip to learn that some Kent locals had burned down the campus ROTC building the night before. The next day, visiting the school, Walsh heard gunfire. ‘The vibes were amazing. Everybody stopped dead in their tracks, knowing what it was, but asking each other what that sound was anyway. I got to the site 30 seconds after it happened. People started to scream and cry. I even saw a National Guardsman throw down his gun and sob, ‘What the fuck have we done!’ The whole town went into shock. Nobody was allowed downtown, all the bars closed. The whole scene totally fell apart. Everybody gave up, and so did I. It was too heavy to have been there.”

Two days later, Walsh was back on the road for his final days with the Gang. “The band began to turn into a big group preoccupied with bucks. Everybody started buying big cars. The emphasis came off good music and creating; that was all left behind. I got fed up with the whole flash guitarist, heavy metal thing we were going toward. They money was great, but I felt like a whore. I played the remaining dates and quit.”

Joe wrestled with an invitation to move to England and join Humble Pie; he decided instead to move to Boulder. No sooner had he hit Colorado than he learned Belkin was misrepresenting his split. “He told people that I was addicted to heroin and that I was drying out,” said Walsh. “He knew it was a lie, but he was anxious to play me down. He was afraid the James Gang wouldn’t make money without me. He didn’t tell the public that I’d left the group until they played a horrible gig in Santa Monica where they were booed off the stage and had vegetables thrown at them. I laughed when I heard that. I would have been booing, too.” Belkin, reached in Cleveland, where he manages the James Gang, denied Walsh’s charges.

Walsh took what turned out to be six months off to study ham radio and plot his next move. “I didn’t even play the guitar,” he said. “I was so sick of it all. I just got drunk a lot, ran around the mountains and waited till I felt creative again.”

When he emerged it was to make Barnstorm, an ethereal solo album. “I was thinking I was going to be James Taylor. I went out, played all nice love ballads, and people said, “What? What’s he doing?’ After eight months, Barnstorm (Kenny Passarelli, bass; Tom Stephenson, keyboards; Joe Vitale, drums, and Rocke Grace, keyboards) was happening, and I was rocking again. You either gotta rock or be great at the quiet stuff. I wasn’t good enough as the introspective singer/songwriter. I wasn’t being true to myself, either.

“But I was fighting hard, trying to buck bad management. All I wanted was half a chance.” Walsh fired Belkin, went through a three-week business hookup with manager Dee Anthony, then turned to his agent at Associated Booking, Irving Azoff, begged him to quit and become his manager. Azoff accepted.

“Irving got me work,” said Walsh, “quick. I’m sorry it took me so long to realize what a creep Belkin was.”

Walsh did a second album, The Smoker You Drink, the Player You Get, and the song “Rocky Mountain Way” led the album into gold country. “It was great,” said Walsh, “to have my paranoia of failure relieved. I knew I was on my way.”

Beginning with Passarelli’s departure last winter to play with Stephen Stills, Barnstorm began to dissolve into an impermanent battery of pickup musicians. Walsh retired the name for his latest concert tour. “I wanted to be part of a group; still do,” he said, “but not at the expense of the music. The Smoker album was the peak of Barnstorm. Now, the band has run its course. I want to put together a new scene around So What.”

Until the tour began, Walsh lay low in Studio City. “L.A.,” he reflected, “can make you nuts. There’s always somewhere to go and some schmuck you’ve never seen before who’ll slap you on the back and say, “‘How ya doing? Great to see ya!’ Hanging out just blows your time. Before you know it, it’s three in the morning and you’ve forgotten all your work. I’d rather stay home.” He got up to answer a ringing telephone and sighed.

“Besides, the yard needs work.”

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #181 – Cameron Crowe – February 27, 1975