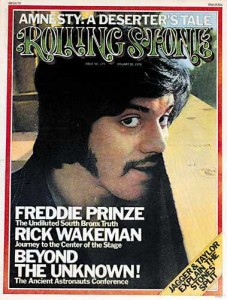

Rolling Stone #179: Rick Wakeman

Journey to the Center of the Stage

“Have you heard the gag about the ten-year-old twin brothers, Peter and Paul?” A Howard Johnson’s coffee shop full of ditchers from a nearby Pittsburgh high school casually eavesdrops on Rick Wakeman’s lunch-time tale. “Well, they’re the filthiest pair of kids you’d ever want to meet. I mean, it wasn’t, “Tuck me into bed, please mum?” It was, ‘Fix the goddamn covers, bitch.'” Rick bends to take a loud slurp from a soup spoon, his blond waterfall of hair drawing a curtain across his face. “So anyway, one night their parents decide the only way to clean up Peter and Paul’s language is to beat the crap out of the next one that swears.

“Sure enough, the next morning at breakfast, the mother asks Peter what he’d like to eat. “I’ll have some fucking corn flakes,” Peter growls. So the father immediately jumps up and begins to sock, stab, maim and ax the kid until he’s just a pulpy mess lying in a pool of blood. Really gross. Dad sits back down and asks Paul what he’d like to eat. Paul just shrugs and says, ‘Well, I’d be a cunt if I asked for corn flakes.'” The entire coffee shop explodes in guffaws. Wakeman, always the class clown, leans back in his seat, basking in the laughter. He loves it.

The lunch is a quick take of Wakeman, who at 25 seems to be at the front edge of a cresting wave of interest in a classically informed, jazz-inclined, rock-based hybrid music that encompasses John McLaughlin, Herbie Hancock, Yes, Pink Floyd, Emerson, Lake & Palmer and European groups like Magma, Tasavallan Presidenti and Tangerine Dream. Wakeman skates the classical perimeter like a caricature surfer, tall, lean and blonde, loose and witty enough to cover the high-mindedness of it all in a mask of infectious humor.

It’s been six months since he bailed out of Yes, surely one of the world’s most prosperous bands, on the eve of a multimillion-dollar summer tour. There’s been no time for regrets. With a two-album catalog of solo works to peddle, he promptly took off on a 20-stop tour of North America’s largest halls and arenas. Despite sizeable crowds, the month-long journey lost a substantial amount of money. Credit that to a payroll listing a 118-person entourage, a rented Lockheed Electra and the expensive David Measham and his National Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir of America. “It’s not really a bloodbath,” insists Yes Wakeman manager Brian Lane, “just a light shower.” One rock manager computes that it must have been a six-figure shower, but for Wakeman that’s light. He invested $50,000 in the album production of Journey to the Centre of the Earth with the attitude, “It wasn’t wasted, it was invested.”Journey is approaching platinum status, its predecessor, The Six Wives of Henry VIII, is near gold, and the skyrocketing record sales are expected to more than recoup the tour expenses. More important, one senses, the roadwork provided Wakeman with an invaluable morale boost, confirming his decision to leave Yes.

Much of the solo tour’s venues were ones he visited last spring as part of Yes. “It’s no use to play the small halls for the sole sake of selling them out,” he assures himself while walking to an afternoon soundcheck at the UFO-shaped Pittsburgh Arena. “That’s just wanking off. It’s better to delay the gratification and play for a three-quarter house. If you do well, the next time you’ll sell it out. That was always the Yes strategy. Our plan for American success was extremely well calculated…” A moment later, the afterthought: “To a point.”

That point, Rick is quick to say, was the Tales from Topographic Oceans album and its subsequent tour. Based on Paramahansa Yogananda’s Shastric scriptures, the esoteric double album made little sense to fans weaned on “Roundabout,” from the group’s 1972 album, Fragile. “To play music,” Wakeman says, “you have to understand it. I didn’t understandTopographic Oceans. That’s why I hardly played on it. It frustrated me no end…and playing the whole thing on tour, I got farther and farther away from it. Deep down inside, I don’t think I was the only member of the band frustrated on that tour.

“You see, a piece of music, just because it was written three or four years ago, shouldn’t die. Gone are the days when you hear a record for two months and then it just disappears. People are writing pieces of music to last. One of my all-time favorite songs-not just because I played on it-is “Heart of the Sunrise,” from Fragile. Incredible tune. “Long distance runaround”…”I’ve Seen All Good People”…they’re great songs. So why not play them? I feel very sorry for anyone who saw us for the first time last tour. All they got was Topographic Oceans shoveled down their throats. I had to give my notice on that tour.

“It was blatantly obvious that Yes was headed more and more in that direction. I figured if I stayed it would be a series of rows that would produce nothing but grief for all parties. You know, it’s funny; I quickly found out where half my friends were at. ‘ Hey man, fuck your ego, stick it out. You’ll be a millionaire before the year is through.'”

Wakeman studiously avoided the press after announcing that he would quit Yes following the tour, leaving composers Jon Anderson (vocals), Steve Howe (guitars) and Chris Squire (bass) to fiercely defend their work. One night a writer for Circus magazine wandered into Yes’s dressing room after their set. Eager for feedback, Anderson asked what the writer thought of the show.

“I thought it was boring,” the writer replied, matter-of-factly. Howe and Squire quickly joined the confrontation. Howe, who composed most of Topographic Oceans, asked, “What was the problem with it?”

“There weren’t enough songs, not enough melodies.”

“Not enough songs?” Anderson was amazed. “Not enough melodies?” He began singing melodic portions from the piece.

The writer headed for the door. “Don’t ask me how I liked the show,” he said. “Ask all the kids that walked out halfway through.”

Wakeman, hearing the story out, chuckles at the recollection and wonders aloud why most musicians have no sense of humor. “The guy had a point anyway,” he says. “I probably would have walked out halfway through, too.”

Wakeman’s humor apparently played a role in the break with Yes. Howe told a reporter, “Yes was a straight-faced band and Rick wasn’t.”

The backstage area, as always, is a visual cacophony of stray orchestra, choir and band members of all ages, sizes and colors. Head in hands, a rumpled David Measham (who has, on occasion, conducted the London Symphony Orchestra and otherwise tried to marry classical forms to rock, as on Neil Young’s Harvest) sits off in a corner. Rick wanders over. “Are you all right?”

Long pause. “Yeah.”

“Sure?”

“I guess.” Measham rubs day-old stubble and whimpers. “Somebody put something in my drink last night.”

“Oh yeah?” Rick is worried, suddenly. “What do you think it was?”

“Alcohol.”

After several years as the only meat-eating boozer among Yes’s health-watching vegetarians, Wakeman took great pains to make his first tour strictly an alcoholic one. No drugs, no smoke-just booze, booze and more booze. He is the beer drinker’s beer drinker; no fussing over brands, anything from the tap will do. The musicians are rated in the official concert program according to their drinking prowess. And if the mountainous backstage stash of beer, wine and tequila isn’t enough, everyone repairs to the hotel bar for a marathon. Predictably, they’re to be found again at 11:30 at the hotel bar.

“In most situations where an artist has brought a completely independent orchestra on the road with him, the musicians simply collect their pay and perform with clinical, but detached perfection.” Tour coordinator Bob Angles talking, who was responsible for assembling the orchestra on two weeks’ notice. “This time the players are so enthused that they’re even adding their own embellishments to the music. They think Rick is a genius. They love him.”

One senses in Measham’s pal-ish attitude the same level of respect, though in conversation he’s more likely to be complaining about untended business in London-TV commitments and the Symphony-than talking about the tour.

The camaraderie is not surprising, considering that Wakeman is far from the tempermental artiste. He knows the nicknames of the 70-odd musicians and keeps track of intraorchestra romances, playfully chiding the blushing participants. The mood is infectious. It’s summer camp and nobody wants to go home.

“Rick,” Angles continues, “is your basic nice guy. He’ll never say no. The other night he spent a couple hours in the dressing room talking with some people like they were old friends. The next morning I asked him who they were. He told me he had no idea.”

There is no opening act for Wakeman’s two-hour show. The first set opens with two numbers from the band, a sextet of unknown British musicians (Jeffrey Crampton on guitars, Roger Newell on bass, Barney James on drums, John Hodgson on percussion and Garry Pickford-Hopkins and Ashley Holt handling vocals). Some members of this band performed with the London Symphony Orchestra on the live recording session of Journey earlier this year. By the time Wakeman emerges, only to disappear behind his bank of keyboards, mellotrons and synthesizers, the Pittsburgh audience is wild. They applaud the various Henry VIII excerpts that make up most of the first hour’s music. A Charleston sendup, complete with four strobe-lit dancing flappers, leads into the break. If the audience is any indication, Wakeman’s fans seem far from a curious fleet of Yes addicts. “Hell, I’ve got both his albums,” one 23-year-old college student says. “I like Yes too, but it seems to me that they can’t decide between keeping or alienating all the 14-year-olds. It’s all good music, though. It’s new music. That’s what interests me most.”

The second set, reserved entirely for Journey to the Centre of the Earth, finally incorporates Measham and company (the choir and orchestra file on surprisingly quickly, with no tuba-test interruption), as well as narrator Terry Taplin. Out of the darkness, in an intentionally melodramatic baritone, Taplin booms the introduction to Jules Verne’s sci-fi classic…And so the journey from Hamburg to Iceland begins. And the music swells.

Backstage, Angles overrides the music with an explanation for the conspicuous absence of actor David Hemmings, who narrated the album. “Rick and David are fabulous friends. They were really looking forward to being on the road together. Two days prior to the tour, though, Hemmings was called away on assignment. So with one day left, we found Terry. The Ed Murrow of Jules Verne he’s not, but he works out fine onstage. The only problem is that Terry gets livid when the reviews read, ‘David Hemming’s narration, was a bit overpowering, but overall the celebrated British star of such films as Blow-Up…” Angles laughs deviously. “We’re going to set his chair on fire the last night of the tour.”

The complex staging wasn’t all fun and games. Wakeman, intent on foolproofing the show, stayed awake for most of the week-long rehearsals in New York. “When there’s unfinished business,” says a friend, “Rick will work at it until it’s either finished or he collapses.” Usually it’s the latter. During Journey album rehearsals he dropped cold. The diagnosis: complete physical exhaustion. Since then he’s been hospitalized for serious bouts with ulcers and emphysema. He’s under doctor’s orders to budget his energy and to cut down on a two-pack-a-day smoking habit. He covers even that level of seriousness with a throwaway line: “You’re as healthy as you feel,” he scoffs. “I feel great. Care for a smoke?”

The Pittsburgh show got a frenzied, standing ovation (following Wakeman’s impish encore of TV commercials-orchestral embellishments of Chevy, Juicy Fruit, Coca-Cola and Bold detergent melodic spiels), but Wakeman was distressed afterward. The monitors had exploded halfway into Journey, and though the audience didn’t seem to sense it, the piece became a shambles of blown notes and cues. Measham and Wakeman locked themselves in the dressing room to debate future policy while changing into street clothes, with Rick, as always, in a T-shirt and brown leather pants. In character, the exchange was short and simple:

“Next time we’ll just stop the show until everything gets fixed,” Rick said, wriggling out of his white cape and pants to reveal blue-and-red spotted briefs. “The people will understand. They want a decent show too.”

A reviewer from a local paper, sitting silently in the room with his date, soberly interrupts: “Why is it that all English rock stars wear print bikini underwear?”

“I don’t know,” Rick says to the surprise guest, not missing a beat. “Why is it that all English rock stars wear print bikini underwear?”

“No, seriously. Ian Hunter wears the same kind of underwear as you do.”

“Don’t forget the Bee Gees, Pete,” reminds the writer’s date.

“Right. The Bee Gees too.”

“I’ll tell you something,” Rick deadpans. “We all share the same pair. It’s worked out great so far, except when the Bee Gees stretched them rather badly on their last tour. It’s a bit of a tight fit, you know, getting all three Gibb brothers in one tight pair of print bikini underwear.”

“No, seriously. The Bee Gees played with an orchestra when they came here too. ‘Cept it wasn’t really classical music like you guys.”

Rick pours himself a Scotch and grumbles. “Classical music has become a status symbol rather than an art form. People seem to be laying out 35 bucks for a ticket just so they can casually mention at the office the next day that they’ve been to a classical concert a couple of months ago and watched the audience very closely. Fellow in front of me slept through the whole thing, but when the orchestra finished, he woke up, jumped to his feet and gave them a standing ovation. It’s silly. People also seem to think that classical music somehow legitimizes rock & roll, which is just a lot of bullshit…C’mon David, let’s go back to the bar.”

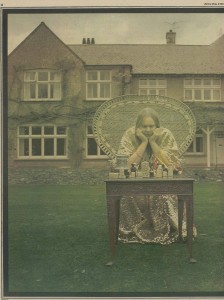

The plane flight to Cleveland was a short trip hop over turbulent air. Rick, forced to stay in his seat by stringent tour stewardesses, was content to down beers and discuss his newfound responsibility. “All you can do is follow your heart,” he said. “If someone was to list the ten biggest musician cliches, that would surely top the list, but it’s still the truth. I believe very strongly in what I’m doing. It takes me over a year to write something, prepare it and iron out the faults before I’ll play it before an audience. If I get booed off the stage, then I’ll obviously deserve it, but at least I will have bombed on my own terms. To me, that’s better than playing something that’s a guaranteed success. Topographic Oceans was a guaranteed success even before it was recorded. To go onstage and earn a lot of money from it…well, I felt like we were not only ripping people off but ripping ourselves off too. Touring with an orchestra and choir and all, I get knocked a lot for trying to tackle a style that’s supposedly above my head. If that’s what I’m doing, I can’t help it. I don’t deliberately sit down and say to myself, ‘I will now write another classical/rock extravaganza.’ I don’t work that way.” Wakeman has been working on his next album with a 45-piece orchestra, to be released early this year: The Myths and Legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table.

Behind the funny exterior, there lurks a virtuous Rick Wakeman. “I’m a great believer in that if you’re going to do something you should do it properly…If you believe you can do it better or as good as someone else, then you can do it. If you can’t, then don’t bother.”

Yes’s Jon Anderson, talking about the difference in background (“I wanted to put ‘musician’ on my passport, now I’m a musician.”), points out: “He didn’t always sound like Rick Wakeman. He was a musical mimic of all his classical influences. Now, of course, his originality and his trademark of playing all those incredible instruments onstage at the same time is well known. So he has grown a lot.”

Wakeman entered England’s prestigious Royal Academy of Music at 16, never expecting to be sidetracked by rock & roll. He wanted to be a concert pianist (his father, Cyril, was a pianist for the Ted Heath orchestra; Rick began lessons at age four-and-a-half), but after studying piano and clarinet for 18 months, he left the Academy to teach music. He didn’t last long at that either and began working recording sessions for – among others – T.Rex, Cat Stevens and David Bowie. It wasn’t long before Dave Cousins, ever on the lookout for talent, invited him to join the Strawbs. Rick accepted. His first tour with the group doubled as a honeymoon with his wife, Roz.

(There is a glimpse of the nonmusic life of Wakeman, through Roz. The couple has two homes – a $125,000 estate outside of London and a seashore farm – two kids, Oliver and Adam – for whom Wakeman spent several hours and $500 toy shopping in New York-and two hobbies. He collects cars – 36 antiques which he hires out to film companies and interested celebrities – and she collects animals. Dogs, mostly, and so many in fact that he asked her before the tour to please not add more while he was away. He phones and, hearing a background whimper, said, somewhat world-weary, “Another dog?” “No,” she said, “an anteater.”)

Wakeman recalls the Strawbs as “my wild oats period. I’d jump around on the piano and kick about. Got all that rubbish out of my system.” He stayed with the group for 15 months and two albums. A Collection of Antiques and Curios and From the Witchwood. “The whole band got on so well as friends that none of us would take the chance of hurting each other’s feelings. We could never criticize each other. After a while, everything became very bland.” He began to moonlight as a session musician. For Bowie’s Hunky Dory; he became an integral part of the studio band. Several months later, he was at a crossroads, with two big offers: One was to join Bowie’s now defunct Spiders from Mars; the other was to replace Tony Kaye at the keyboards of an up-and-coming progressive band named Yes.

“I was doing a lot of sessions at the time,” Wakeman says, relishing the retelling of a favorite tale. “I had just arrived home at three in the morning after having done a three-day stint with about six hours’ sleep. I fell into bed and it was one of those things where your head hits the pillow, you’re out cold. Then the phone rang. I couldn’t believe it. I covered me earholes up and Roz picked up the receiver….He’s only just come in…He hasn’t been back for three days because he’s been doing sessions…He’s really very tired…’ I was furious. ‘Gimme that phone!…Who’s that?‘ And this voice sort of meekly says, ‘Oh, hello. It’s Chris…Chris Squire from Yes. How…how are you?’ I said, ‘You, phoned up at three in the morning to ask how I am? What the fuck do you want?’ He said, ‘ Well, we’ve just come back from an American tour and we’re thinking of having a change in personnel. I saw you doing some session when I was down at Advision Studios with our manager, Brian Lane. I wondered whether you would be interested in joining the band.’ Like a prick, I screamed, ‘No!!!!’ and slammed the phone down.

“Next morning I couldn’t remember what happened. I asked my wife if someone called. She told me what happened. So I raked through my record collection and pulled out Time and a Word. I hadn’t even played it yet. Later I thought, ‘Yeah, this is interesting.’ Anyway, they phoned up again and asked if I’d like to join. Actually, it was Brian who phoned up and said, ‘Come along, we’ll have a talk.’ I figured it couldn’t do any harm; I was well fed up with the Strawbs at the time; so I trotted over to see Brian. I felt like an asshole because it was so beautifully arranged. Brian took me to a rehearsal, which I later found out was a prearranged audition for me. The music was amazing – it really knocked me out. I never said, ‘Yes’ though. It was almost understood that I had joined Yes. The next day we started recording Fragile.”

Another American tour and their first gold single (“Roundabout”) and album (Fragile) followed in quick succession. Yes was still a relatively faceless entity, and when fans searched for a focal point, they settled on the whirling blond dervish surrounded by keyboards. It was Wakeman who landed the magazine covers. It was Wakeman who got the biggest crowd response. Wakeman…the new kid.

“We were never really very close socially, so it’s difficult to say if they felt any animosity toward me for getting on the magazine covers and stuff. When we spoke, it dealt almost strictly with music. In fact, we’ve spoken more since I left the band then we did when I was with them. To a hazard I guess, I would say that Yes is fairly happy right now. Not really happy per se – even though they’ve always played positive music, they’ve never been a happy band. Yes is a very serious group. They lived off their dramas. The backstage dramas were unreal, absolutely unreal. We would have full-scale rows over minute sound and technical details from the night before. Somehow that tension worked to our advantage, though. It put certain urgency into the music.”

A lot of the tension was between Wakeman and Jon Anderson. Steve Howe says, “Rick and Jon’s relationship was always very tense. Rick was constantly upset by things Jon said to him. Rick, being classically trained in music, felt Jon wasn’t to give him criticism. I know it’s a very easy thing to happen because if you don’t know Jon then it’s not hard to take him the wrong way. And if you don’t know Rick, it’s easy to take him the wrong way too.”

The fact that Brian Lane manages both Yes and Wakeman prolongs the relationship -could it turn the falling – out into a conflict? “It’s too early to tell,” Rick says, uneasy with the question. “Since I left, Yes has been in the studio. Brian’s been working with me. When I go back to England, he goes back out with Yes. I can’t see any problems from my end. I hope Yes doesn’t kick up a stink, ’cause I’d hate to see him put in the position of having to choose between one or the other.”

Lane, who was affectionately / suspiciously given the tour nickname “Deal-a-day-Lane,” was a fairly successful business accountant who stumbled into rock management when he heard the field was lucrative. Yes was his first venture. He has all the right ingredients: flawless business instincts, no humility and a dryly devastating wit. He loves to tell about the time he spotted Groucho Marx in Los Angeles. He stopped the car, got out and said to Groucho, “I’d like to get your autograph before you die.” Groucho, Lane says, went into fits of laughter, signed the autograph and said, “Better now than later.” Then there’s the time in Cincinnati when Lane laid down in front of an airplane to keep Yes from missing their flight…

Lounging in a gaudy Cleveland hotel suite (“It looks like a honeymoon spread for two faggots, doesn’t it?”) before the show, Lane says that splitting his talents won’t end up destroying him. “It wasn’t my idea for Rick Wakeman to join Yes,” he says. “He was asked to join the band by its existing members. But from the moment he joined the band I had an obligation to do my best for him. So they’ve had a musical difference. That’s too small a thing to lose the relationship over. I wouldn’t desert Rick or any other Yes member. Should Jon or Steve or Chris or Alan [the drummer, Alan White] go solo, I’d support them as well.

“It’s been a difficult time for Yes. They took a lot of slagging over Topographic Oceans. I think that was unjustified. To my knowledge, nobody was ever forced at gunpoint to buy the record. People laugh at Yes for their seriousness, but at least they don’t have any drug problems. That seriousness produces good music. Listen, after Rick’s next album he’ll get the same thing. ‘Rick Wakeman’s pretentious,’ ‘Rick Wakeman’s sold out,’ ‘Rick Wakeman’s overdone it.’ As far as my managing both groups, it’s my moral obligation. Money isn’t even a factor.”

Wakeman, entering the room in time for the last statement, begins cackling wildly. “Okay, okay,” Lane says. “It’s a factor, but the bottom line is that I happen to like where both Yes and Rick are at. Maybe I’m the only one in the world who does, but that’s the truth of the matter.”

Wakeman’s replacement in Yes, Swiss keyboard player Patrick Moraz, has stated that he will maintain a solo career. “But he won’t assert himself in the way that Rick did,” Lane says, popping a chocolate mint in his mouth.

“I can’t see Jon letting him,” Rick mutters.

“It’s not a question of Jon not letting him.” Lane licks his fingers. “It’s a question of me not wanting to be associated with failure. He won’t have the public following to make a solo career worthwhile for a few more years. Half the problem is that joining Yes is like joining a musical Mafia. It’s very much ‘one for all and all for one.’ You’re in? You’re in. You want out? You get rubbed out.

“The situation that arose with Rick was a contractual thing initially. A&M Records, which he was signed with through the Strawbs, said he could play with Yes provided he cut solo albums. At the time, nobody had the clairvoyance to see how big either one would become. Basically, there’s too many guys…”

“Like you,” Wakeman prompts.

“Like me…”

“Who are Jewish.”

“Who are Jewish and…”

“And have got little beards.”

“Got little beards…Cut it out, Rick. This is my fucking interview.” Lane chases Wakeman out of the room and sits down again. “Now I forgot what I was going to say.”

Finding the thread again: “Patrick Moraz isn’t a leader. He’s a follower. He’ll work out fine. There’ll be no problem with him wanting to break out of Yes’s confines.

“Yeah, I think divorce is a good simile to use in describing the break between Rick and Yes. When everything dies down and they all run into each other in a restaurant one day, it will be very warm and friendly.”

“Brian?” Rick is listening in again. “I seriously doubt if we’ll ever meet in a restaurant.”

Cleveland, by everyone’s standards, stood out as a tour highlight. The buzz was still strong on the next morning’s flight to New York and a tour-closing sell-out of Madison Square Garden. Wakeman ran up and down the aisles-no seat-strapping turbulence this time-and bellowed, “I seem to have lost my book on how to shout quietly,” coaxing laughter out of even the more staid orchestra members.

A few minutes later, struck with a rare sentimentalism, he decided to say a few words over the PA system. “First, I want you all to know that I deeply appreciate all your support during the past month. It’s been quite an undertaking for all of us. I hope we can all be together for the next tour. Thank you all, very, very much.” Heartfelt applause. “Second, I’m sure everybody will be glad to hear that you’ve all been a part of my special loss-sharing program.”

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #179 – Cameron Crowe – January 30, 1975