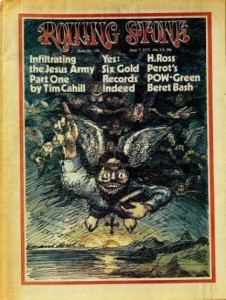

Rolling Stone #136: Yes

Yes: The Band That Stays Healthy Plays Healthy

Alec Scott used to roadie for Marmalade. “Those guys had girls throwing themselves at their feet. After shows, there’d be stark-naked young ladies running through the hotel corridors. And orgies? Like you wouldn’t believe. Part of my job was to keep everything under control. . . .”

A year later, today, Alec is the road manager for Yes. His job, he says, consists largely of locating a heath-food restaurant in every city the four-fifths vegetarian group plays. “Basically, Yes aren’t a raving band,” says Scott, a little sadly. “After gigs, they’ll usually either head back to the hotel rooms and write- or have some health food.”

On the eve of their sixth straight gold album, Yes began their 1973 tour in Tokyo, March 8th, and worked across Japan and Australia. From there they would hit the United States to continue through Easter. Bookings had provided for a six-day layover. And because they had worked the three weeks in Japan and Australia without families, Yes would be joined by wives and kids for the week off before the first US show, in San Diego. Rick Wakeman, for one, is unhappy. “I don’t like holidays,” he says, gritting his teeth, mocking fury. “I like to continue working once I’ve started. When we finished Australia, the band was playing really well. But because all the families have come over, the musical contact has been lost. It’s a great shame . . .” Wakeman left his wife Rose and their son Oliver home in England.

It is Saturday, Disneyland Day for Yes. This morning, the band, the families, the roadies will be shuttled by limousines to Anaheim and the spot everyone has demanded they see while in California.

The Beverly Hilton lobby, where the party of 15 will gather, is glutted with Secret Service men, L.A. police and curious hotel guests. Tonight the Hilton plays host to a ceremonial tribute to film producer John Ford, and the guest of honor is Richard Nixon.

Brian Lane, the manager of Yes, grimaces at the scene, grumbles something to the effect that had he only known, Yes would have stayed somewhere else. Two nights ago, Lane had returned to his suite to find it completely barren. His luggage and clothes were gone; so was all the furniture, the TV, the lamps and the beds. Only after a frantic call down to the desk, was he told that his room had been chosen as a stakeout for the FBI.

Lane pouts, “I’ll tell you something. This band will never stay in the same hotel as President Nixon again.”

The elevator doors part and out strides Wakeman. “Hey,” he shouts at the newest member of Yes, drummer Alan White. “Listen to this one.” John Wayne strolls past, unnoticed. “You see, this bloke has just come from seeing a porno movie when he realizes that his hat is gone. He trots back to the fellow at the door and says, “Could you let me back in for a moment. Me hat’s in there.” And the guy at the door just looks at him and says, “I believe your hat, Sir, is hanging in you lap!'” The two go into hysteric convulsions.

The limousine ride to Disneyland is a rather unscenic one filled with puffing factories and brash billboards. The only passenger, save for one, in the third of three cars is Eddie Offord, Yes’ producer.

Offord travels with Yes to coordinate sound equipment and act as consultant on the road. He is the sixth member of the band. He is also building and financing a Yes studio, where the group’s next LP and their inevitable solo albums will be recorded. An instantly likable fellow with frizzed hair and a good-sized beak, he gave up the chance to produce an Emerson, Lake and Palmer live album to join Yes on this tour.

“I had my first contact with the band,” he recalls, “when Tony Colton asked me to work with him in producing their second album, _Time and a Word_ . . . I’ve produced them ever since.”

“I never thought they would make it, though, that’s for sure. I thought they were just too far out of line of music that was being bought. It was a great shock to me when their albums got in the charts.”

Asked to evaluate the personalities, and roles of each Yes member, Offord grins the acknowledgment of a somewhat loaded question. He begins with founder and singer Jon Anderson.

“Jon is the spontaneous member of the band. He writes or co-writes all the songs and lyrics and has a lot of nice ideas for arrangements, although he hasn’t got any talent for playing an instrument. He’s very spiritual.”

“Chris Squire [bass] . . . now there’s the technical side of the band. He’s very much into working everything out. He and Jon are like yin and yang. They balance each other out, “Fishy’ [He’s a Pisces] is a little over-technical and pre-arranged and Jon is a little over-spontaneous.”

“Steve Howe is great. He’s a great guy and a great guitarist. Really mellow.”

“Alan white lived with me for a year before he joined the band. Alan’s a great jammer. A lot of funk he’s got. He’s really gonna help bring Yes down to ground, I think. They kind of got a little carried away with _Close to the Edge_. In fact, they almost went over the edge. Alan White is definitely going to bring Yes back to their roots.”

Offord pauses a moment. “Now Rick . . . is a very different case altogether. He’s the only one who refuses to eat health foods. He’s also a boozer and the rest are druggies. Rick is the only one that’s somewhat of a raver. It took him quite a long time to become accepted into the band. . . .”

The three cars pull up to a crowded Disneyland and deposit their passengers at the entrance. Jon Anderson is the first one to inquire at the information booth. “Could you tell me if there’s any place here that has fresh vegetables?”

Wakeman is next. “Where’s the bar?” he asks.

“I’m well aware that I’m somewhat different from the others,” Rick later admits over a plate of roast beef and a mug of beer. “I find health food pretty tasteless. I’ve tried quite a few things out, and . . . I find it very boring. It’s not particularly exciting sitting there with a knife and fork over a lettuce leaf.”

Yes was formed in 1968 by Anderson and Squire, who found the other original members through classified ads. Wakeman joined in the fall of 1971 after the forced departure of an uninspired Tony Kaye. Wakeman now admits that fitting in with the rest of the band wasn’t as easy as he swore it was to the English pop press less than a year back.

“It took me a year and a half. Not until last October, November. You see, when I was with the Strawbs, I did all the lead figures. I’d also jump on me organ and smash it up and God knows what other normal, stupid trips you get into during the adolescent period of your musical training.”

“Anyway, when I joined Yes, suddenly I was in a band where nobody even talked about having a blow or taking a solo. Everything was just arranged. I found it very difficult to accept. Jon and I were at each other’s throats every five minutes.”

“Jon and I come from totally different musical backgrounds, you see. I had a thorough musical upbringing which began when I was an infant. Jon hasn’t had a day of musical training in his life, but he has this incredibly artistic brain. He’s got a lot of the artistic moods and ideas that I know there’s a lot of 20th century composers who’ve been thoroughly schooled would give their right arms for. It’s amazing.”

“We used to argue like shit, then we finally sat down and really started talking. It was right after _Close to the Edge_ and Bill [drummer Bill Bruford] had left the group. I was really worried because I thought, “God, if it’s taken me over a year to try and get into the band, what’s gonna happen with the new guy?’ So we sat down and talked, and Jon and I realized we were going after the same thing, but we were just going about attaining it in different ways. We had the define-all slag-off where Jon said all the things that he thought was wrong with me and I said all the things I thought was wrong with him. We listened to each other and learned to work together.”

Running his thumb slowly across the smooth surface of a Groucho Marx button, Jon Anderson, the spiritual one, is seated silently in his dimly lit hotel room, deeply involved in the dramatic classical music booming from his cassette machine.

“Yessongs signifies an end-of-an-era for us,” he murmurs after a few moments of near-meditation. “For the past few years we’ve been on a continuous cycle of hard work where we tour, record a new album, tour to promote it, then record another album . . .it can go on and on if you let it. Yes has outgrown that now. After this tour we’re going back to England for five months to rehearse and record the next album, which hopefully will be a double-album concept. By the next time we tour, our shows will consist only of us. We’ve talked about playing a three-to-four hour set, which will probably only give us time to perform the new album and “Close to the Edge.” The future is very exciting for me.”

“I think Yes is gonna get a little funkier, too. The band has reached the stage where the only addition we need to create a better band is to have a little more funk. It’s like playing our records, then putting on The Band. What I see in The Band, I don’t see in Yes. The overall . . . funk of it all.”

“It’s very strange if you start thinking about all the names,” Anderson continues in a stream-of-consciousness fashion. “They are so true of what the particular group is doing. The Band. The Mahvishnu Orchestra. . . .”

John McLaughlin and the Mahavishnu Orchestra is a subject springing up constantly in conversations with the band. “It’s the spirit in which they do what they do that is so important,” guitarist Steve Howe explains. “They make just spiritual and beautiful music. They have something Yes is looking for a little more of. Brilliant improvisation.”

Howe, who is now planning a solo album of synthesized orchestration, also likes to relate an incident which occurred on Yes’ second tour of America. Yes was to perform two consecutive nights on Manhattan Island with the Kinks, and the first evening their set lasted several minutes longer than scheduled. Ray Davies was furious. “He pulled our plug out first,” Howe says, laughing. “Then he kicked and punched Rick when we got offstage. It was crazy.”

The next night Mahavishnu had been added as a third act on the bill. “When we got there early the next day to do the sound check, it was a real tranquil situation to walk in and find McLaughlin and his guys warming up. Once again we all realized that performing onstage was a friendly idea, a good idea, whereas the night before we had thought, “This is a really bum trip.'”

By the afternoon of the band’s opening night at the San Diego Sports Arena, the worst case of show-fright jitters belongs to promoter Lenny Stogell. “We’ve done everything we can do,” Stogell assures himself from a loge seat, staring out across the cavernous empty arena. It is the first presentation by Stogell’s and partner Bill Owens’ new production company, Colony Concerts, and for two weeks the local print and radio media has been permeated with ads. Still, advance sales had been slow.

With the sound check completed, Alan, Jon and various roadies begin a spirited game of soccer on the floor. Still onstage, Rick is checking out his nine layers of keyboards, Moogs and Mellotrons. Trying out a series of sound effects, he calmly and matter-of-factly rocks the arena with the deafening sound of falling bombs, explosions, sirens, orchestras and a 160-piece choir shouting “hallelujah.”

Backstage, Steve and Chris go through the ritual of tuning up their myriad of guitars. “They . . . wouldn’t . . . let me into . . . the Rickenbacker . . .factory,” Squire gripes between bass thumps. “Haven’t . . . let anybody . . . in there for a . . . long time. Not even Pete Townshend. . . .” He lovingly replaces his tuned instrument in its case. “C’mon,” he motions to his wife Nicki, “let’s go to the hotel.”

At the Sheraton Inn Coffee Shop, the Squires cross-examine the waitress, happy-day tag-named Louise, on the quality of the cheesecake.

“Why don’t you just try it,” pleads Louise, “and if you don’t like it, I won’t charge you for it.” A deal. Louise shuffles off.

It is only after a long pause that Chris agrees to expand on his statement made to Melody Maker that King Crimson mastermind Robert Fripp had “stolen” drummer Bill Bruford from Yes.

“I think Fripp stole Bill’s imagination, one can say that much. Or at least he entreated Bill enough to leave us.”

“He took Bill on a fantasy,” adds Nicki.

“It was friendly persuasion . . .he played upon Bill’s dreams, I think,” says Chris. “Bill always wanted to be involved in a kind of jazzy thing, but I think Bob Fripp launched him into it prematurely. Bill is a young drummer and he could have waited a few more years before really getting involved in any heavy music. You see, that’s the problem with Bill. He really wanted to get places fast. He rushed into it, I feel, with his eyes a little bit closed. Maybe now he’s finding out the consequences.”

“Your cheesecake,” Louise cuts in. Food inspection begins. The talk ends.

In a two-room suite upstairs, Steve, Jon, Eddie, Alan and Rick crowd around the television set patiently waiting out the final moments of Sonny and Cher in anticipation of Elvis: Aloha from Hawaii.

On the phone in an adjacent room, Alec Scott is talking to Lane, who is backstage at the sports Arena with bad news: The PA system is shot, and the show will begin two hours late, at 10 PM.

So it is not until midnight when Stravinsky’s “Firebird,” Yes’ recorded show-opener, swoops from the ailing sound system and a patient sell-out crowd raise some 8500 lighted matches into the air to greet Yes, who tear into “Siberian Khatru.”

The show moves into overtime for the rent-a-cops, and every minute is costing Lenny Stogell several hundreds of dollars. Stogell shrugs it off like a graduate from the Mike Lang Woodstock School of Promotion. “Sure, we’re gonna lose money, but the show ended up doing great and these kids were terrific, waiting for two hours without rioting or causing any kind of trouble. They deserve the best show possible. It’s worth every cent just to see them happy. . . .”

The Yes show takes itself very seriously. Totally devoid of stage patter or theatrics, it is, as Lane put it, “down to the music itself. It isn’t part of the act to piss on the audience and get a big howl. They’re very straight-faced about the whole thing.”

And yet, visually Yes remain quite stunning. With Michael Tate’s intense lighting brightly illuminating each member, yet throbbing in multi-colors with Alan White’s every beat, the image is anything but serene.

This set draws largely from Fragile, The Yes Album and mainly from Close to the Edge, the entire album of which is performed onstage. It is Wakeman, however, who steals the show with a tour de force five-minute solo. His floor-length sequined cape sending slivers of reflection across the sea of faces as he twirls from instrument to instrument stationed around him in semicircle, Wakeman recklessly slams out short excerpts from his Six Wives of Henry the Eighth solo LP interspersed with the repertoire of jarring sound effects. As the dry-ice smoke rises from the floorboards, Steve Howe sounds out the opening licks to “Roundabout,” which is met with a double wave of applause. One for the solo, the other for Yes’ big AM hit of last year. The last song of the set, when the final notes die away it is1:30 Friday morning, a weekday, and a fact which fails to keep the crowd from demanding two lengthy encores of “Starship Trooper” and “Yours Is No Disgrace.”

Taking 20 minutes to summon the strength to rise from the dressing room benches, Yes, generally pleased with their performance for the morning, file slowly out the door and head for the limousines that will deliver them back to the Beverly Hilton.

“Rick?” a glazed longhair nervously approaches Wakeman. “Hello,” Rick replies to the stranger. “Rick, I have something I have to talk with you about. It’s very important. Could we talk?” “Well, I’ll tell you . . . we’re uh . . . just leaving right now. I’m very sorry. Is . . . is something wrong?” “Rick, you must believe me. I’m Jesus Christ. I like your records and I enjoyed your show tonight, but I’m afraid I have to save you. . . .”

“I’m very sorry,” Wakeman apologizes, “but I really have to go. It’s been, uh, nice meeting you though.”

“That’s quite all right, my friend,” Jesus understands. “Someday we’ll meet again along the path. . . .”

Wakeman climbs into the car and slams the door. “Who was that?” asks Alan. Wakeman smiles faintly. “Fellow says he’s Jesus Christ.”

“Oh yeah,” White yawns.

“Yeah. Doesn’t look anything like his pictures, does he?”

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #136 – Cameron Crowe – June 7, 1973