Kansas – 1977/1978 Official Tour Program

There were no blaring trumpets, no declarations of The Next Big Thing, no gaudy ad campaigns . . . just four exceptional albums of music that defied all the stereotypes. The word-of-mouth travelled quickly. A dedicated cult following soon flourished into hundreds of thousands. Then came “Carry On Wayward Son,” a song more powerful than anything played on AM radio in years . . . and suddenly everyone else was in on the secret.

KANSAS had taken their place among the great bands of our time.

Success came to the band on their own painstaking terms. “It’s the one reason we can sleep at night,” remarks guitarist-keyboardist Kerry Livgren. KANSAS refuses to obscure their music with garish on-stage theatrics. They rarely “pose” for group photos or submit to press interviews. The mass acceptance of the band’s uniquely artful style of rock still baffles the media . . . and KANSAS likes it that way.

“We just try to keep it to the music,” states vocalist-keyboardist Steve Walsh. “The fans know what we’re all about. We love to play. We’re just . . . guys.”

Well, not quite. In actual fact, KANSAS is a volatile, if sometimes modest mixture of long-time friends and virtuosos. The road and stage crew have been there since the humble beginning. Most of the band members have been playing together since high school. Even KANSAS’ much-acclaimed producer, Jeff Glixman, is their former road-manager. He is still their touring soundman.

On the heels of their most triumphant year yet, there is now a fifth KANSAS album – Point of Know Return. Where some bands might choke on the challenge of following up a double-platinum masterwork like Leftoverture, KANSAS outstripped even their own lofty expectations. You will be hearing much of the new album tonight in a novel context . . . the streamlined 1978 KANSAS stage show has been built around the Point of Know Return concept.

Indeed, KANSAS has discarded any trace of a safety net. This is a special time to observe them, as the sextet boldly forges into the next phase of their seven-year-career. It also seems a proper juncture to pause and re-cap.

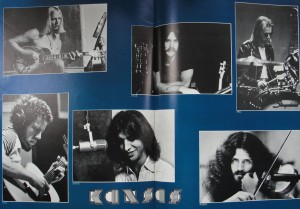

For the first time, this is KANSAS’ own story in words and pictures.

“We came up in a different scene than most bands. The midwest is no musical mecca, you know. We all had years of destitute poor times with nothing to fall back on . . . except ourselves. We didn’t have the money to go to L.A. But if you can survive and then make it big . . . you really learn the true meaning of the world ‘band.’ We feel very lucky about our past now . . . ”

The saga begins in Topeka, Kansas – a wind-swept city of 150,000. Rock and roll was the dream ticket out and by the late sixties every kid in town had a band. Young Kerry Livgren – now Kansas’ primary writer and guitar-keyboard-synthesizer whiz – was certainly not to be left out. He attacked the over-saturated local market as the dedicated leader of a psychedelic-surf band called The Gimlets.

“There was only so much room,” recalls Livgren. “and before long, all the people who weren’t musicians dropped out.” Among the few still left playing were Livgren’s former classmates from West Topeka High – drummer Phil Ehart and bassist Dave Hope. They merged in ’70 to form a regional super-group. All they needed was a name. “We wanted something to really describe us,” says Livgren. “Something that meant more than the Chocolate Eyeball . . . ”

They called themselves KANSAS. (For the record, Chicago – supposedly the first group to use a strictly geographical monicker – was still C.T.A. at the time.)

“Our greatest goal in the beginning,” adds Livgren, “was to maintain our popularity in spite of whatever trend was happening at the moment. That was most important to me. No compromises for a hit.”

KANSAS would undergo a treacherous course of twists and turns over the next seven years, but they would never break that original promise. Ironically, it would be Livgren’s own “Carry On Wayward Son” that was an unintentional hit years later. “We’d put a few out and had just given up on singles,” he says. “Sure as shit, as soon as we stopped trying . . . we got it!”

Now living in Atlanta with his wife, Victoria, Livgren spends much of his time off the road working diligently on his newest compositions. “In my wildest dreams” he someday envisions a solo album that might touch on each of his musical passions – from all-out rock and roll to Gustav Mahler. Also looming on the horizon may be a full concerto. Someday.

“I have to say,” Livgren smiles thoughtfully, “I can’t imagine a world in which I don’t play in KANSAS. We have so many memories, it’s ridiculous. When we get telling stories, watch out . . . ”

“This band is your basic small-town opera . . . ”

Drummer Phil Ehart was the first to take a dramatic leave from that original, configuration of KANSAS. With an ear to all the heavy metal thundering out of England in the summer of ’72, Ehart had to follow the muse. He sold the school bus he’d been using for band transportation and bought an airplane ticket to London. He arrived a complete stranger, lugging around a drum kit and answering musician’s classified ads. H wanted some on-duty band training.

“Needless to say,” Ehart recollects, “it wasn’t an overwhelming reception. Everytime I called someone up, they either wanted me to play country and western or blues like a good American . . . or they wouldn’t talk to me at all.”

When his working visa ran out three months later, Phil Ehart returned a wiser, even more driven man than before. Now he wanted to start a band himself. “And I vowed I would put together a group better than any of the ones I’d seen over there.”

Ehart began by calling Steve Walsh, a gifted writer and inspired singer he had played with a few seasons back. Walsh was washing windows and living out of a trailer in St. Joseph, Missouri. “I couldn’t believe he was out of work,” says Ehart wondrously. “He was ready for anything.”

It was a good omen and a better place to start. Walsh offered Ehart the extra room in his trailer. Ehart continued making calls from his new base.

Robby Steinhardt was next on the list. A brilliant electric violin player, Steinhardt had retired from music and was living off a dwindling inheritance when Ehart reached him. He sent Steinhardt a tape. A few more calls later, Steinhardt had been coaxed back into the mainstream.

“Then my phone rang,” remembers Ehart. Rich Williams, yet another guitarist-survivor from West Topeka High, and old-friend Dave Hope had just left a successful show band touring the mid-west. They wanted in on the new band.

“Those guys?” Ehart snaps his fingers. “It took me that long to say ‘Hell yes!”

As White Clover, the five-piece band built their sound in the bars and clubs of the area. All they needed was another writer . . . and one day Ehart heard some interesting news about Kerry Livgren. Livgren’s band had encountered a stretch of terrible luck. A major recording contract and extensive tour had just fallen through.

Ehart wasted no time in zeroing in, “I took him out for a ride and said ‘Kerry, why don’t you get rid of those wimps you’re playing with . . . and join us.” Ehart grins. “Prime psychology: hit a man when he’s down.”

Livgren was just exhausted enough of fronting his own band that he accepted immediately. Livgren also brought with him the name he had never abandoned. White Clover became . . . KANSAS.

Their first demo tape was the basis for their contract with Kirshner Records. KANSAS received the news from a pay phone in a noisy Dodge City bar. “I never had the slightest doubt that someday we would be a big group,” Ehart declares sincerely. “As soon as everybody saw us and got adjusted to the fact that we weren’t some country fiddle band, I could see it happening . . .”

Now widely considered among the more dynamic and precise drummers in rock, personable Phil Ehart takes quiet pride in having assembled the band. “We don’t have a leader . . . one guy who thinks he’s the big deal. We’ve always been very careful to prevent that. We’re all good enough musically to carry our own on stage. If anybody starts believing they’re a star and their ego gets out of hand, we just say ‘Don’t be an idiot.’ It works . . . we know each other too well for it not to. And the success doesn’t mean a thing if it stops being fun.”

Ehart now lives in Atlanta too, with his wife Terry. Their precious free time is often spent preening those ’59 and ’71 Corvettes.

His “hand grenade” hair flying in the on-stage breeze. Robby Steinhardt approaches the mike and beckons to a sold-out crowd. “Good evening ladies and gentleman . . . and welcome to KANSAS.” There is never any stopping the pandemonium.

In the earliest days of KANSAS, stage spokesman duties fell to Dave Hope. “But there wasn’t any way around it,” comments Phil Ehart. “Robby, playing that incredible violin and looking as striking as he does . . . the audience always focused on him. He used to stand there and not move a muscle . . . ”

Thanks to gentle nurturing from fans, fellow band members and group manager Budd Carr, Robby Steinhardt has grown into KANSAS’ indispensable frontman. He draws audiences into the band’s vision with his unpretentious verbal openness . . and slays them with the most novel lead-playing in rock. “It’s all been natural,” Steinhardt says of his wailing stage presence. “I try not to think about it too much. I just do what comes naturally once I’m up there.”

Like his father distinguished musicologist Milton Steinhardt, Robby is a voracious student of the art. “I’m bothered sometimes that we play so loud I have press my ear to the instrument,” he notes. “But the excitement you get from a concert propels you into an entirely different direction. I could, but I don’t think I ever would play in an orchestra…”

What was it about Kansas that drew Steinhardt out of his early retirement? “It just seemed from what Phil was saying, that he was interested in the same kind of versatility that I had given up trying to find. I guess it came down to impulse. A lot of it was a gamble . . . ”

Steinhardt figures he won that gamble most decidedly with the Point of Know Return. “All the albums are special to me,” he explains. “But something happened with this one that hasn’t happened in the studio with us before. We’ve always been a live band that could hold their own . . . but this time there was a kind of magic in the studio I’d never seen before. We’ve learned to work together better than ever. The fact that I can’t quite put it into concrete terms tells just how elusive that magic is. It’s a new spirit for KANSAS.

“And it’ll be obvious listening to the new album.”

Steinhardt is careful to protect his privacy. Happy to make a sequestered home with his wife Mary in Tampa Bay, Florida, he spends much of his time there boating and practicing.

“It’s important to keep fresh with new ideas,” Steinhardt emphasizes. “Stagnation is a crime. It will never be a problem as long as there is a KANSAS or else there won’t be a KANSAS.”

Caustic Dave Hope, with his sly smile and sinister mustache, creates the constant impression of impending mischief. Those that knew him in his West Topeka High days remember him as “a serious hellraiser.”

“I smoked in the bathrooms,” Hope shrugs. “They didn’t.” He spent a year in military school nevertheless.

Hope likes to call KANSAS a musical “Heinz 57 . . . and his rebellious spirit is proud of the groups refusal to crank out the same old three chord rock. “Nobody has ever told us what to play or how to play it. If we fail, it’s our own faults . . . if we succeed, we owe nobody anything. That’s the way we want to keep it.

“We toured and worked our butts off . . . and we did.”

There were those times, of course, when it looked doubtful. Before flying to New York to record their first album, KANSAS was told not to bring their own equipment – it was already rented. They arrived to find a studio full of amateur instruments and amps . . . and a producer who’s last project was Barbara Streisand three years earlier.

Hope cuts through the tales of their agonizing struggle. “We made it work,” he says defiantly. “The album turned out better than we’d all feared.” Finished in eight weeks, KANSAS took seven more months to finally see release. The band didn’t wait – they immediately hit the grueling treadmill of constant roadwork. “That’s a helluva transition between clubs and concerts,” Hope continues. “Whatever you may have accomplished, you have to start again at the bottom.”

There was a pleasant surprise awaiting. The years of club experience had turned KANSAS into deadly competition for headliners. Several major acts heard and refused to perform with them. “For awhile it was testy” admits Hope. “We kinda loved obliterating the big acts.”

The dilemma was quickly solved when their debut LP sold remarkably well. KANSAS was soon headlining themselves . . .

“Nobody in the business could believe it. We didn’t dress up . . . we weren’t actors. The music, to us, has always been our whole lives. We’ve never compromised.”

Look closely for the man in the white tux. It’s worth the effort. Back there by the drum risers, Rich Williams contentedly plays some of the finest electric and acoustic guitar you’ll hear.

“I’ve never been one to get up there and wiggle around,” he explains sheepishly. “I figure if someone else wants to do it, fine. I would feel uncomfortable. My frame of mind on stage is the same as it’s always been . . . I’m playing with the band.”

A journeyman guitarist who built his expertise in the smallest and rowdiest dives on the mid-western circuit, Williams is another one for setting his own trends. Until as recently as the recording of the breakthrough fourth LP, Leftoverture, Williams wore only loose-fitting, faded overalls. “My tastes up until that point amounted to hot food and cold brew. All I wanted to do was hang around, play and be comfortable.”

Now Williams hangs around, plays and wears only white tuxedos. “Amazing what a little money can do,” he cracks.

Williams finds the KANSAS legacy a simple testimony to hard work. “We set out to do exactly what we did . . . we made a lot of mistakes along the way, but we just kept on plugging through those albums and tours. That was the key.”

He has a particularly clear view of KANSAS’ LP’s. Of Song For America: “The band liked that album a lot. All the songs were long and fun to play . . . but disc jockeys and program directors couldn’t play anything off it. So it wasn’t as big an album as it could have been for us . . . ”

On the next album, Masque: “A natural swing of pendulum. We had missed playing shorter songs, so we recorded some. It could have been better, but we learned a lot making that album. We all knew the next album would be the one . . . ”

Leftoverture: “We’d been playing for eight solid months, touring by the seat of our pants. We had no credit cards, no money . . . we just put everything out of our minds and worked on pleasing ourselves as best we could. It worked on stage . . . and when we went into the studio, we tied right in. Our taste and the audience’s had matured into being the same. It was the greatest feeling . . . we all still have it.”

Point of Know Return: “Our songs now are geared to the stage. They’re real energetic. We’ll have fun playing this stuff. I heard the whole album for the first time the other night and couldn’t sit still. We’re twitching to play it. It’s gonna be . . . a riot.”

Williams lives an anonymous city life in Crown Center, Kansas City with his wife Donna. “It’s right next to a big shopping mall,” Rich mentions. “I’ll only move so far uptown.”

It can be said very simply. Steve Walsh, the trademark voice of KANSAS, is a true singer’s singer. A master keyboardist and the second of KANSAS’ two excellent writers. Walsh happily designates his first love. “I have a great time playing,” he says. “But I really get off singing a good song.”

He still remembers hearing himself on radio for the first time. He and his wife, Marie had just finished a McDonald’s dinner. “We were dirt-poor,” Walsh recalls, “and the first album was just out. Then, all of a sudden, “Can I Tell You” popped on the station.” Walsh pauses dramatically. “It sounded terrible to me. After a certain point, I just can’t be objective.”

Ah well, another of six unrelenting perfectionists. “It is your job as an artist,” Walsh declares, “to take a hand in the whole concept and feeling. KANSAS gets involved at every level – from our album covers to the concerts . . . to this program. That’s exactly why we’ve made the progress we’ve made on the five albums. We want to make records that we would go out and buy ourselves. Our goal is not to be rock celebrities. If that happens, fine, but it’ll never change us.”

Walsh was stunned when, after KANSAS was recently featured on the CBS special State Fair America, his neighbors in Atlanta began to treat him a little differently. Like he was a . . . gulp . . . star.

“I’m the man of many faces,” Walsh chortles. “I try to keep my privacy as much as I can. There’s a whole lot of sanity in your private life. The two lives create two different personalties. A balance between the two is of the utmost importance.

“If you inject your road personality into your personal life, then you never walk off the stage. You’re always on, which is bad. Likewise if your personal life surfaces on the road. Then people don’t see you as they want to see you. And you fall.”

It is Walsh who best describes the careful balance KANSAS strikes between rock stars and everyman. “When we look out at the faces in front of us every night . . . more than them looking at us, we see them looking at themselves. Up on stage and doing it. Changing positions with us. That’s really cool, because we’re able to create a whole different reality for them each concert we give. KANSAS is a completely unique, whole world. I don’t want the audience walking away trying to grow some new eardrums . . . or with their retinas burned out by lasers. I want them to say ‘Man, they took me to a different place in time . . . and that’s why I’m gonna come back and see them again . . . ‘”

Steve Walsh also has one more goal – to get his ’55 T-Bird in shape. “Right now,” he laments, “it doesn’t stand a chance against that ’59 Vette.”

Extraordinarily uncompromised artists or unaffected small-town boys . . . KANSAS is out for a good time either way. The years of grumbled frustrations at being “stranded in the mid-west” simply taught them the most valuable lesson of all. How not to break up.

“This band is so much bigger than any of us bozos,” David Hope confides. “How could we break up? Look at us! A couple of us are into cars . . . a couple of us have mustaches . . . a couple of us like Genesis . . .

“I mean, what’s the big deal?”

Welcome to KANSAS.

Cameron Crowe

September, 1977