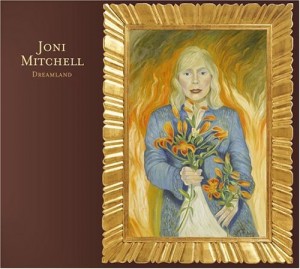

Joni Mitchell – Dreamland

STANDING IN JONI MITCHELL’S PAINTING ROOM, surrounded by her latest work, it’s not hard to feel the rush of her creative process. There is a new series of landscapes, and Mitchell is asked which canvas was the breakthrough. She thinks for a moment, and then points to one. Early in its life, the painting was a nearly complete and mostly satisfying portrait of a rain forest, but Mitchell kept working on it until the entire work deepened and changed, and even an early influence of Cezanne became part of the under-painting. The work, still untitled, grew into what it is now – full of richness, finished, wildly her own, with a sense of life so powerful you can feel the wind in the trees. Looking at it, you can’t help but realize the journey of the painting is the journey of Joni Mitchell herself.

She was born in Fort Macleod, Alberta, on Canadian prairies, the only child of Bill and Myrtle Anderson. She was a popular teen, with a passion for lindy dancing and secret musical heroes like Edith Piaf, Miles Davis, and Rachmaninoff. There were childhood dreams of being a classical pianist and a great painter, but she never thought of herself as a singer. Then, on the same day that a dentist pulled her wisdom teeth, “with bloody sutures still in my mouth,” she plunked down 36 dollars for a baritone ukulele “and went from an extroverted good-time Charlie to a total introvert.” Her best friend from high school recenlty recalled to her, “The uke went everywhere with you; you were always practicing, even standing in line for a movie.” Another friend would implore her, “Put that thing down, Anderson, or I’m going to break it! Come and dance!”

She dances into whole new circles. Playing folk music at art college in Calgary was an easy way to pick up 15 dollars a night in clubs, “money for smokes, bowling, and the occasional movie.” The songs were ones she’d heard on albums by The Kingston Trio and Judy Collins, but in her attempt to copy the arrangements from records, she began to develop an unmistakably personal style. Soon, on a training heading east to Ontario for the Mariposa Folk Festival, she wrote her first song, about traveling and humming of the wheels. It was called “Day After Day.”

Life was also thundering down the tracks. She was pregnant out of wedlock. In February 1965 she gave birth to a beautiful baby girl, but having no income, she was forced to put her child in foster care. Then she met American musician Chuck Mitchell, who got her the occasional booking in the Detroit area. They began performing as a duo and married in June 1965. Facing a grueling tour schedule and a bad marriage, she came to the agonizing decision to give up her child for adoption. It was a secret she’d keep for more than 30 years.

She covered the ache with a fevered forward motion. She wrote prolifically, and her songs progressed in huge leaps. She was more than beautiful, with a poet’s heart and a still-strong attachment to the style and dancing of her youth. The combination was unforgettable to all those she met along the way.

Those early songs became her first round of classics. “Both Sides Now,” recorded by Tom Rush and later one of her early heroes Judy Collins, was a “meditation on reality and fantasy…the idea was so big it seemed like I’d just scratched the surface of it.” Another new one, “The Circle Game,” was Joni’s answer to a song she’d heard from fellow Canadian artist Neil Young. Together the two songs formed a memorable dialog – two budding songwriters, then barely 21, musing on the subject of lost youth.

More songs came swiftly and in large batches. Sometimes Mitchell would play them only two or three times in clubs and abandon them. By the time of her first album, she had 60 compositions, songs about movement and trains and the indelible characters she’d met on her travels. She’d written the songs in all-night sessions, in the back rooms of rough-and-tumble clubs, or in the small apartment she shared with Mitchell on West Ferry Street in Detroit, and later in New York, where she moved after her marriage dissolved. Eric Anderson showed her an open-G tuning for guitar, and it opened many compositional avenues. Soon Mitchell was inventing her own tunings and with them came harmonic movement that was sophisticated and unusual. An early review in a major New York publication boldly declared her one of the most gifted composers that America had yet produced and likened her to Schubert. Humbled by the comment, she kept the clipping in her wallet for years and continued writing.

The early characterization of Joni Mitchell as a hallowed hippie icon was never quite accurate. Steeped in the rhythms of her teenage juke joints and dance halls, she was rock ‘n’ roll in attitude. She may have been left to watch the boys [CSNY] take their rock-star bows or go off to play at the Woodstock Festival without her, but Joni stayed behind and wrote the anthem.

The songs were often startling, wise beyond her years. Yet even an emotionally raw album like Blue was also filled with her own brand of humor, a Chuck Berry-like level of friskiness. Sometimes she’d even play a character, mimic a voice, laugh spontaneously, or even address friends, like the memorable Peace Corps worker she’d met on a Greek vacation (“Carey”). It was a long way from the girl who couldn’t even dream of herself as a vocalist.

Court and Spark was another watershed recording, an album of startling clarity, and all the highs and lows of romantic attachment came under her study. More instruments and colors were added now too – it was a pop album like no pop album before it, the beginning of a new phase in her talents as an arranger. “Help Me,” the album’s opener, was her first Top 10 hit. Now Joni Mitchell’s music was, for some listeners, as compelling as her words.

There was no looking back, and each new album would reach a surprising new level; her early years and influence had simply become the under-painting. The Hissing of Summer Lawns upped the ante even further, and “The Jungle Line.” included here, is a club mix favorite even today. It’s also one of the earliest examples of sampling, with loops taken from a Burundi war chant. Mitchell presided over the session (for the most of her career she worked without a producer), calling out the cuts to her engineer Henry Lewy. Bits of tape were dangling all over the console. Analog days indeed.

In 1976 she drove two friends back East in a used Mercedes-Benz and traveled back to California alone. The solo return trip provided the imagery for one of her greatest songs. “Amelia,” and the Earhart-ian spirit of flight characterized the entire Hejira album. “Furry Sings The Blues,” taken from that recording, was an indelible snapshot of Memphis’ legendary Beale Street, then on the verge of destruction. Mitchell’s conversation with bluesman Furry Lewis, also a master of the open tuning, is re-created in her vocal and in her song-spoken characterization. She really should try acting someday.

Sonically, the bar was raised again with Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter. The double-album sessions were an exciting time for her, a period of further envelope pushing. Soon, the great jazz composer-bassist Charles Mingus would come calling with project ideas. Her work and spirit had captured his attention. Their subsequent collaboration, finished by Mitchell after Mingus’ death, both excited and challenged her audience. Mingus marked the end of that explosive second phase of her career and the beginning of the period she calls her most creative and best, a run of five albums recorded in the ’80s and ’90s for Geffen Records. There was no precedent or playbook for the path her career would follow in the next few years.

The Geffen recordings were almost completely at odds with the glib pop landscape of the day, and though that easily qualifies as a badge of honor, those vivid albums, the product of much work and sterling songwriting, went comparatively unheard. Justice arrived when Turbulent Indigo went on to win the Grammy for Pop Album of the Year, but finding appreciation for those recordings is a still-current passion for Mitchell. The day after winning the Grammy, Mitchelle opened a newspaper to find herself absurdly relegated to “Then” in a then-and-now roundup of songwriters in the ’90s. “This would never have happened to an Oscar winner,” she noted. (A powerful and timely selection of songs from this period were recently sequenced by Mitchell and issued as Beginning of Survival.)

Joni Mitchell’s work in the new millennium has been equally bold, a re-imagining of earlier songwriting context. Her vocals are deeper and more expressive than ever, and Both Sides Now and the most recent Travelogue provide several of the tracks selected for this set. Like many a visionary before her, Mitchell’s projects sometimes take a few years to find their most appreciative audience. But like those waves hitting the beach, back these recordings come, with increasing timeless power. Check out The Who’s Pete Townshend, writing on his web site, just the other day: “I am listening to Joni Mitchell’s CD called Travelogue. It is a revisit to her career with full orchestra. It is, quite simply, a quantum masterpiece. Joni is a the peak of her powers. Even her paintings seem to me to be especially revelatory gathered as they are in the sleeve. Someone told me last night, after The Who’s show at Madison Square Garden, that she plans no more recording. If she never made another record, this one will stand as a testament not only to her work, but to the greatness of American Orchestral music.”

It’s true – Joni Mitchell is currently on hiatus from songwriting and recording. Perhaps the muse is on hold, she says, while she continues to refurbish her valued later-period work. Or maybe she’s waiting for a few more waves to hit the beach. Or maybe it’s even deeper. In 997 she reunited with the daughter she hadn’t seen in 32 years long years. She says, “I started writing when I lost my daughter, and I stopped when she came back.” Now she paints. Her remarkable painting continues in full force, rarely displayed in public galleries in America but generously on display in the packaging of releases like this one.

Like her painting, like her songs, like her life. Joni Mitchell has never settled for the easy answers; it’s the big questions that she’s still exploring, like no one else, whether it’s with a paintbrush, a guitar, a ukulele, or standing here, right now, in a room lined with fresh canvases. Over there on the table is a yellow legal tablet with the final listing of the songs on this album., written out in longhand, with a few last-minute changes. Such is the power of her work, and such is the difficulty of selecting some of her songs for a single record. Her songs belong so powerfully to those who hear them. How could you choose one and leave another behind? And then you realize, it’s easy if you think about it.

The masterpiece is Joni Mitchell.

Courtesy of Rhino Records – Cameron Crowe – September 14, 2004