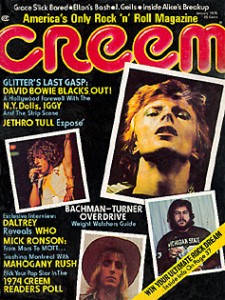

Ian Anderson – Creem Magazine

Ian Anderson Explains How Martians Hear Music

“Now hold it. I get to meet the cat? And rap to the cat?” Bob, a 19-year-old Jethro Tull fanatic, was creaming in his jeans.

“All you have to do is get to the Beverly Wilshire this weekend.”

“Get to the Beverly Wilshire this weekend? I’ll fucking clobber the first guy that gets in my way. Fuck, this is all right. All right.”

“Just make sure that you’ve got some decent questions lined up. Make him work.”

“I’ll have questions up the ass, Jack.”

Surely a major part of Jethro Tull’s appeal is the almost-taunting fashion with which Ian Anderson defies his fans to understand–and in some cases, even enjoy–his music. Tull devotees consider themselves in the elite ranks of rock and roll fandom. Their duty, as they see it, is not so much to simply appreciate Jethro Tull, but to painstakingly analyze Anderson’s musical crypticisms. As a result, to a boundless legion of 15 to 20 year olds, Ian Anderson is Bob Dylan.

So on the recent event of being offered a crack at Anderson’s first major interview in almost three years, CREEM opted to send a trio of hard-core Tull aficionados to pose the questions. The fans, no doubt, would shower the frizzy-haired flautist in a barrage of detailed questions concerning minute lyrical details. Ian Anderson would sweat. Great idea. Can’t miss.

It did. Ushered into Anderson’s Beverly Wilshire suite, CREEM interviewers Bob, Eric (18), and Brenda (17) opened their line of questioning with Bob’s “Just what were you trying to say with Thick as a Brick and Passion Play? And why isn’t WarChild another concept album?”

Anderson promptly snuffed any possibility for a sizzling semantic exchange. “First of all, I appreciate the fact that you listen.” His richly resonant speaking voice was a bit patronizing. “I don’t really want to get into specific comparisons and explanations, especially about Passion Play and Thick as a Brick. I don’t want to start people off trying to figure out where the new album is in relation to the last two. Believe it or not, they all mean something. But I don’t wanna start making comparisons. Next year we’ll worry about that, if we worry about it at all, which I certainly won’t.” Anderson had politely, if not charmingly, set the ground rules for a standard question-and-answer session between interviewers and their subject, rather than between fan and artist. Unargumentative but undaunted just the same, the CREEM crew switched into Plan B and forged ahead.

“Does it make you mad,” Eric wanted to know, “that most critics put down your records?”

Anderson wasted no time with a haughty reply. “Very much so. I’d be less than human if my blood didn’t boil when I read something that some punk kid at some newspaper…like he’s hardly out of his nappies, and he has the gall to say that my music is bad or unimaginative. I find that totally irresponsible.” Our interviewers bobbed their heads in lemming-like agreement. “That’s criticism for entertainment. It hurt us a great deal.”

The ice is thawing. “How do you think WarChild will go down with the critics?” asks Eric.

“Oh, they’ll probably hammer us again. This time it’ll be ‘Tull has gone commercial and copped out. We still hate them.’ One of the reasons I haven’t done interviews is that I don’t want to be on the defensive. By the time WarChild comes out, I will have finished doing my interviews I had scheduled. Then I won’t have to answer to the inevitable slagging. It won’t have happened yet.

“It’s distinctly worrying, because I know that the last few records have been difficult to listen to. WarChild, so I’m told, is a lot more accessible. I don’t know if I like that or not. I’ve started to worry that perhaps people will think it’s a simple record and they’ll play it at parties and they’ll play it when they’re stoned and they’ll play it in their car–instead of actually sitting down and making an effort to listen. I’m also worried that it may accidentally come across as a little bit of a return to the early Tull style. For example, I play quite a lot of flute on the new album but it’s in no way a return. I actually find the flute tedious. The sax is much better. Anyway, my attitude has always been that the group is a live concert act. Basically we sell records as souvenirs. So far there has been a lucky coincidence. The songs we like doing are the songs that people like listening to. Which just goes to show that they all have very good taste.”

Bob asks, “What became of last year’s much-publicized announcement that Jethro Tull would retire from the stage to put together a full-length film?” Anderson silently opens a Heineken. Good question.

“I was feeling sorry for myself.” Swig. “The band had been constantly working for six straight years. We’d done 19 American tours, recorded six albums, and I wanted some time off. At the same time we were talking about doing a movie, so it seemed like a good idea to use that as an excuse. At least we weren’t going to sit and vegetate or live in vast English country estates with servants and carriages and whatever it is people imagine that rock stars do. I think the period we actually stopped for was something ridiculous, like two days.

“We had no definite plans for touring again so we started laying the groundwork for a movie. I started to write a lot of music. All different kinds. Some of which I knew would come out on a Jethro Tull album, some of which would be thrown away, and some of which might be good music, but it wouldn’t be fair to capitalize on the Tull name to sell it. I don’t mind disappointing people at all, I just don’t want to trade too much on previous success. We’ve made a lot of music that people could not possibly have enjoyed. I’m proud of that. Anyway I wrote quite a lot of music for the film and put a lot of work into the screenplay.”

“Will the movie ever come out?”

“I suppose,” Ian shrugs. “We just decided to go back out on the road again last week. So that takes care of the year it would have taken to do the film. I got so many letters that I suppose it was inevitable I would wind up doing it again. I enjoy it.”

Brenda wonders if the return to touring won’t put a nice bundle in the bank, too.

“Now I know that this sounds like a really clever thing for me to say, but all I have to show for what I’ve been doing these past seven years is a nice suitcase that I’m very fond of and a few instruments. I don’t have any possessions. I don’t own anything other than that. I don’t even have any money. For tax reasons, it all ends up in companies. I’m the only survivor from the original group but we all get paid the same money. We all have the same stake in it and we all have the same share of expenses.”

Eric is curious. “Where do you live?”

“In an apartment in London, at the moment. But I’ve decided I’m going to ditch that in November. I’m going to stay in Holiday Inns for the next year or so. I want to write some more music, which I do better in hotels than I do in something I’m pretending is my home. There’s always these constant reminders, like dirty coffee cups in the sink, ashes on the floor, and you can’t pick up the phone for room service. You’ve got to go out and find someone to cook for you, which means having to establish a relationship with a servant on one hand, or a mistress or a wife on the other. That would just make my life more complicated. Besides, I’m totally irresponsible with women anyway.

“I don’t need to go out and jam, either.” Anderson gingerly pronounces the word, much the same way somebody else would say ca-ca. “And I don’t feel the need to go outside to building sites and make friends with Irishmen. It just doesn’t seem necessary. Although if I met one in a pub or something, there’d be every chance that we’d get married, who knows?” Nervous laughter.

“Do you wish Tull was more of a band?” asks Bob.

“Jethro Tull,” Ian counters, “was initially never meant to be anything but a band. I sorta took the group over after our first album, This Was. Mick Abrahams left the group and I was the only one who was able to take control. Clive Bunker (drums) and Glenn Cornick (bass) couldn’t write music. Of course they are gone now and it’s a lot different. The group now is much more of a band. I still write the music, but everyone contributes. During the period of Stand Up and Benefit, it was really down to me. The other guys played backup more or less. I like it better the way it is now.”

Eric’s turn. “Did you feel that Benefit was a big jump from Stand Up?”

“No. The music was just a little more sophisticated. Some of the songs on Benefit I still really like, but it was a bit too much like what a rock group is supposed to be. By that time we were doing all right, we were playing to some sizable audiences and indulging the illusion that we were a name group. That’s a very dangerous thing. We played it too safe withBenefit. It could have been a lot more adventurous. Aqualung was an attempt to move on. It was a different kind of music than we played before. The playing wasn’t so hot and the production was dismal, but the songs were good. I don’t dislike it.”

Aqualung, Brenda points out, was the one album that put Jethro Tull over the top.

“If you’ll forgive me for saying so,” Anderson fires, “I really believe that most of the success of the group has come from the fact that we’ve played a hell of a lot. Aqualung just put a signpost on a certain point in time. A lot of people knew the name and a lot of people also started thinking my name was Jethro Tull. ‘Hey, Tull. Hey, man. Hey, Jethro. Hey Jet.’ I once got called Jet, which I thought was quite attractive I must admit. It wasn’t by a girl, unfortunately. It was by a rather diseased-looking young gentleman from one of the Southern states.”

The phone rings and Ian, dressed entirely in black, strides across the suite to snap it up. It’s his manager Terry Ellis, telling him he is late for an appointment across town to test ride and maybe purchase some motorcycles. “Bikes are my only vice,” Ian would say later. After a few seconds, Anderson hangs up and rejoins his audience for a final statement.

“I’ll tell you something,” he grins. “Before you ever get caught up in trying to figure out the deepest inner meaning of any music, much less Jethro Tull music, just remember that it’s all noise. To a Martian, it’s no better or worse than a buzz saw.”

Courtesy of Creem – Cameron Crowe – January, 1975