Duane Allman – The Day the Music Died

Duane Allman was born in Nashville, Tennessee on 20 November 1946. After gaining a local reputation as the Allman Joys, Duane and his brother, Gregg, joined a studio band – Hourglass – in Los Angeles in the late sixties. Duane’s success on Wilson Pickett’s ‘Hey Jude’ led to a firm fixture as a session man with Muscle Shoal’s Fame Studio (backing Aretha Franklin among others), and the birth of the Allman Brothers Band. Their debut album was released to critical acclaim in New York and Duane’s personal reputation increased. Universally recognized as one of the world’s leading exponents of bottleneck guitar, his career was cut short by a fatal motorcycle accident in Macon, Georgia on 29 October 1971.

Duane Allman had been dead almost two years when I first met the Allman Brothers Band in 1973. I was sixteen, and it was my first major assignment for Rolling Stone magazine. The Allman Brothers were my favourite band, and I was not to be stopped. After ten days on the road with the group, I’d seen every show and taped long interviews with everyone from the lighting crew to singer-organist Gregg Allman.

The band’s publicist had said in advance that the tragic motorcycle death of Duane Allman was a subject not to be discussed, but every interview and every conversation had eventually turned back to that sad topic. They were pained and heartfelt interviews, and I was amazed that the band and crew had been so open with me. The night before I was to leave the tour and write the story, I knew I had something special.

At four in the morning, my hotel phone rang. I was sharing the room with photographer Neal Preston, and Neal picked up the phone. He mumbled a few sentences in a low, nervous voice. I instantly knew something was wrong.

Neal hung up and switched on the desk lamp. ‘Gregg wants you to come to his room,’ he said. ‘He wants you to bring him all your interview tapes, right now.’

A cold fear crept through me. Gregg Allman had been friendly to me, but many others had warned that he was distant and moody. I wondered about the possible psychology of such a close-knit group as the Allman Brothers: an outsider had killed Duane, now another outsider wanted to write about it. I gathered all but one of the fifteen interview tapes and headed upstairs to Allman’s room. I still remember shaking so hard that I dropped the tapes in the elevator.

Allman answered the door himself. He was solemn, his long blond hair was pressed against his head with perspiration. His eyes were fixed on some distant point as he led me inside.

‘Let me see your i.d.’, he said. ‘You could be anybody – hanging around, asking us questions. We told you everything. It’s all on those cassettes.’ He looked over to an empty chair across the room. I clenched my teeth together to keep them from chattering. ‘Duane’s in the room right now. He’s sitting there and he’s laughing at you.’

I noticed an empty whisky bottle on the table and so I didn’t want to argue with Allman. It was a strange and astonishing transformation he had gone through. I hand him all the tapes, and went home the next day believing I’d lost the story. Too many personal questions, too much naiveté on my part.

But Gregg Allman woke up the next day and called his roadie. ‘Why do I have these tapes,’ he wanted to know. The tapes were sent back to me the next day, along with a soul-searching eight-page biographical letter written by Allman. I wrote the story, and never alluded to the incident Gregg Allman would call ‘a nightmare I can’t exactly remember’. He would go through his mother’s scrapbooks to help send early photos for my article, and I would write about the Allmans many times after that, but we would never discuss that incident over the tapes.

I understood, even then. Gregg Allman was still Duane’s younger brother. And Duane Allman, besides being one of the first modern rockers to rise out of the South, was a powerful young man. A charismatic ‘father of the family’ to the Allman Brothers Band, he dies at the very peak of his career. He’d been recording from 1966 to the summer of 1971 and Duane had just seen his first gold record arrive for the seminal Live At Fillmore East album. After his death, the band was left without its inspiration and without its leader. That the Allman Brothers Band were able to continue after Duane, and rise to even greater success without him, is one of the modern miracles of rock.

It’s conceivable that Duane Allman will always be remembered as a self-contained stereotype – the pioneer of southern rock. But like John Lydon and punk rock after him, Allman encapsulated a personality as well as a genre. Duane Allman had an Attitude. Forget the South – Allman knew he was one of the hottest guitar players to come down the pike, period. Besides forming the Allman Brothers Band and guiding them to nationwide success on his own terms, Allman’s confidence also helped loosen the tightest of musical fraternities, the session men.

In the year or so before the first Allmans album, Duane was a studio guitar demon. Under the guidance of producer Jerry Wexler, and Muscle Shoals Fame Studio’s master Rick Hall, Duane powered the sessions behind some of the most influential soul, blues and rock of the sixties and early seventies. Listen to Aretha Franklin’s ‘The Weight’, or Boz Scaggs’ ‘Somebody Loan Me A Dime’, and then listen to Clapton’s ‘Layla’. It could well be the work of three different guitarists, but the spark is unmistakably Duane. Those who knew and worked with him can tell a thousand stories about the long-haired blond kid who stepped in with the catfish-eating professionals and kicked ass. From the very beginning, it appeared that Duane Allman’s success was preordained. But sadly, tragedy also seemed to form an integral part of his short life.

Duane Allman was born in Nashville, Tennessee, on 20 November 1946. His younger brother, Gregg, was born the next year. In 1949, the boys’ father, a first lieutenant in the army, returned home from the Korean War for the holidays. The day after Christmas, Mr Allman picked up a hitchhiker who turned out to be a dangerous mental case and murdered him.

‘You’ve got to consider why anybody wants to become a musician anyway,’ Gregg had said in our first interview. ‘I always played for peace of mind.’

Left as the breadwinner, Geraldine Allman sent the boys to Castle Heights Military Academy in Lebanon, Tennessee, while she studied to be an accountant. In 1958, the family moved to Daytona Beach, Florida. Duane was rapidly becoming a problem child but by contrast in the summer of 1960, thirteen-year-old Gregg took a nice summer job as a paperboy. He went to Sears department store one day for a pair of gloves, but his attention was diverted by a display of guitars. He bought a guitar instead.

That same summer, Duane had purchased a motorcycle, a small Harley 165, and earned himself the title of ‘Terror of the Neighbourhood’. ‘He was a real bastard as a kid,” said Gregg. ‘He quit school I don’t know how many times. But he always had that motorcycle, and drive it till it fell apart. When it did, he quit school for good.’

Duane then traded the motorcycle parts in for a guitar like his brother’s. Gregg gave his older brother his first few lessons, and Duane took to the guitar with typical zeal. Instead of returning to school, Duane stayed at home and listened to the local R&B station, studying Chuck Berry and Robert Johnson records. And then Duane finally began to read. Voraciously. In later years, he would do his brother’s Physics homework so Gregg could make band gigs.

After a year of practice, Duane and Gregg were ready to perform. Their first bands were variously known as the Shufflers, the Escorts, the Y-Teens and the Houserockers. They became regional legends on looks alone. There, in the toughest black bars of Florida, was a blues-rock duo with two angelic-looking faces playing songs like ‘I Feel Good’.

Tom Petty, then an under-age upstart living in Jacksonville, remembers hoisting himself up on a cement wall to see a frat dance where Duane and Gregg, then called the Allman Joys, appeared in 1966. ‘Duane just stood there, off to the side, ripping through these great leads,’ recalls Petty, ‘and there was his little baby-faced brother who opened his mouth and sounded like Joe Tex.’

It was on a long tour of what Duane called ‘the garbage circuit of the South’ that the band ran into the high-riding Nitty Gritty Dirt Band in the airport. The Dirt Band’s manager, Bill McCuen, told the Allmans to give up the roadwork, to come to California and really get serious.

Gregg was suspicious – these regional crowds were awful comfortable – but Duane was ready for the shot. Gregg relented, and off to California they went. It all seemed too good to be true, and in fact it was. The record label, Liberty, re-named the group Hourglass, ordered the band to dress in imitation Paul Revere clothing, and told them not to play live in order to preserve the band’s mystique. Amazingly, they complied for over a year. Their material was chosen for them on the only two Hourglass albums. ‘Together,’ said Gregg, ‘those two records form what is known as a shit sandwich.’

It was the ultimate embarrassment for a proud kid like Duane Allman. In one of the band’s few clandestine live dates, they had acquired the favourable attention of Neil Young, then of the Buffalo Springfield, who wrote liner notes on the second Hourglass album. For a while, Young’s respect was all that kept them going. The band were soon forced to hop to several low-rent motels to escape mounting bills and it was at one such flop house in Hollywood that Gregg had wandered past an open door. Lying there was a dead man, a suicide case, with a sheet pulled over him. He’d taken 95 Seconals and left a note. It was an ugly reminder of what had become of their careers as Hourglass. And that is where Duane drew the line.

‘Duane got fed up and when my brother got fed up, he got fed up,’ said Gregg.’ “Fuck this,” he kept yelling. “Fuck this whole thing. Fuck wearing these weird clothes. Fuck playing this ‘In A Gadda Da Vida’ shit. Fuck it all!”‘

The band packed up and headed for Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where Duane paid to have some of their own material taped without outside interference. It was fiery blues, like the old days, and some of the tracks would appear years later on the two fine Duane Allman: An Anthology albums. (Well worth the search, if you ask around.) After those sessions, Hourglass broke up and the Allmans returned to Jacksonville to re-group.

It would not be that easy. Liberty Records called and threatened to sue for an alleged $48,000 investment in Hourglass. They wanted Gregg. For the first time in their lives, much less careers, Duane and Gregg split. Lawyers forced Gregg to return to L.A. to fulfill the contract while Duane stayed behind. For several weeks, Gregg would be given the rare privilege of watching a 26-piece orchestra cut his first album from songs he had written or chosen himself.

Back at the studios in Muscle Shoals, owner-operator Rick Hall was gearing up for an important Wilson Pickett session, a test audition for Pickett’s future recording account. Hall wanted the business, and remembered the hot young guitarist he’d seen recording with Hourglass, so he sent a telegram to Duane Allman in Jacksonville. Duane jumped at the chance of a paid job.

Muscle Shoals, Alabama, was legendary as a straight town. Very tight, very conservative, and very southern, it was also dry: the nearest legal alcohol was over 70 miles away. The good ol’ boys were not quite prepared for a long-haired Duane Allman to stroll into town wearing his best British bluesman shirts and red, white and blue sneakers.

But it was inevitable that Duane would hit if off with Wilson Pickett. Allman knew Pickett’s music backwards and forwards, and Pickett had never been backed by a guitar player like Duane. It was Pickett who gave Duane his studio nickname ‘Skydog’ – ‘Because he hits the heights, man’.

It was Duane who suggested that Pickett recorded ‘Hey Jude’. Pickett listened attentively to Duane’s idea, but at first responded, ‘Hey man, I can’t sing that song. I’ve got a lot of Jewish people working for me!’ Eventually enlightened, Pickett cut the track with Duane on lead guitar. It sold a million copies, and Duane was of course invited to stay on in Muscle Shoals as a regular session man. He was the youngest player working there, and culture shock would soon set in.

‘It was bullshit,’ Duane would remember. ‘One of those cats got a 442 Oldsmobile, and then they all had to have one. Then one trades it in on a Tornado and then they all have to have one… I was getting to like it.’

For all the fame he generated in Muscle Shoals, Duane stayed there only six-and-a-half months. In that time, he also mastered the slide guitar. It would become one of his great trademarks. ‘Most slide players are muddy,’ said Jerry Wexler. ‘Their playing sounds sour. Duane is one of the very, very few who played clean, sweet and to the note.’

Allman was suddenly much in demand and soon his showmanship during recording sessions became as legendary as his musical talent. He’d hem and haw, pace and shout, work himself up into a pitch of energy, and then pick up the guitar. He would scream through two or three takes at the most. Then he’d want to move on. ‘It’s gone,’ he’d say. ‘I’ll try it again tomorrow.’

As Duane moved out of session work, Rick Hall, who had signed him to an exclusive contract, tried recording a power-trio solo album. The results were mixed, and Duane returned to Jacksonville once again in search of the perfect band. By then, Hall had sold Duane’s contract to a young manager named Phil Walden. With Walden’s backing, Duane began sleeping on floors and looking for players.

A couple of weeks later, Duane found himself in the middle of a particularly hot jam between himself, local guitarist Dickey Betts, bassist Berry Oakley, and drummers Butch Trucks and Jaimo Johnson. They were playing in a small room at Betts’ Commune. The jam went on for three or four hours, and when the music trailed off, Duane looked around the room. ‘Man,’ he said, ‘anybody who ain’t in this band has got to fight their way out.’

There was little disagreement among the musicians. All they needed was a singer, and Duane Allman had planned for that. He placed a phone call to California, where a despondent Gregg Allman was considering suicide.

‘I had been building the nerve to put a pistol to my head,’ Gregg had written in the biographical letter that accompanied my tapes. ‘Then Duane called and told me he had a band. He said, “I want you to come down here, round it up and send it somewhere.” I put my thumb out and caught the first thing smokin’ for Jacksonville.’

Luck was starting to turn in favour of the Allman Brothers Band, as they called themselves. Phil Walden suggested moving the band to Macon, Georgia, where he was setting up Capricorn Records. They were glad to be out of the competitive Jacksonville scene and enjoyed living in a quieter place where they could improve in private. The band moves a few blocks away from the local college, and lived in a fraternity house while writing the first album. His L.A. experience behind him, Gregg began to blossom as a writer. In short order, Duane had prodded him into finishing a string of future standards like ‘Whipping Post’, ‘Not My Cross To Bear’ and ‘Midnight Rider’. Much of the other material came from late night sessions around in nearby Rose Hill Cemetery.

They completed their first album, and the Allman Brothers set out on a rigorous two-year tour, doing nearly 500 dates in one Econoline van. Duane called them the ‘Reds, Ripple and Rassaan Roland Kirk days’. They were back on the garbage circuit, but they had a purpose, and more importantly, they had a good time.

The music of the Allman Brothers Band now featured double lead guitars that intertwined hypnotically – almost sexually – in songs that could last for up to 45 minutes. Even then, the music of the Allman Brothers was like backroom bootleg. The feeling between the group and its audience was a strong, and almost forbidden one.

The first few Allman Brothers tours went unnoticed on a national scale. Most of the big-name agents and promoters had seen the group at a Boston showcase, and pronounced them ‘too bluesy’. The prevailing opinion as expressed to the band at the time was ‘Why are they hiding that blond singer – he should be out front like Tom Jones.’ Duane advised the band to forget about it, and keep playing. ‘Opinions are like assholes,’ he was fond of saying, ‘everybody’s got one.’

By the time of their second album, Idlewild South, a ground swell of concert-going support was gaining for the band. Duane had been paid the ultimate compliment when Eric Clapton invited him to play lead and slide guitar for the Layla album. The two became fast friends, and Duane even played a few dates with Derek and the Dominoes, but he never strayed far from the Allman Brothers Band. As the spirit and leader, he also had a new plan for breaking the band wide open. The third album would be the purest of Allman Brothers albums – recorded live at the Fillmore East, Bill Graham’s legendary New York rock venue.

Live at Fillmore East was released as a double album in 1971, and within two weeks it was tearing up the American charts. The group encountered huge crowds at every stop, and more and more young Southern guitarists would seek out Duane backstage and tell him how he had inspired them to break up their lounge acts and play some real music. Duane would smile, sometimes he gave them a guitar. On this incredible high, after solid years on the road, it seemed time to take a short vacation and enjoy some of the success.

It was during that vacation that Duane Allman was killed. On 29 October 1971 Duane had ridden his motorcycle over to bassist Berry Oakley’s house in Macon to wish Oakley’s wife Linda a happy birthday. Shortly after leaving the house, at about 5:45 pm, he swerved to avoid a truck travelling in the same direction. Duane’s cycle skidded and flipped over, dragging him nearly 50 feet. He died of massive injuries after three hours of emergency surgery, at the age of 24.

Duane’s death came as a shocking blow to a public which had just taken the Allman Brothers Band to its heart as the premier American band. After Duane’s funeral, a moving event attended by most of the artists he had played and worked with, the Allman Brothers played their first set without him. The original plan was to take six months off, finish the fourth album, and consider the future. But after only four weeks the band reformed and returned to the road. United in grief, they performed some of their best shows ever even if the band’s famed two-pronged guitar attack was now only one.

‘I used to have nightmares all the time,’ said Dickey Betts recently. ‘Usually it was the same one. In it, the Allman Brothers Band is on the road, and we end up on a show with Delaney and Bonnie, Duane’s old touring buddies. We see Duane at the show, and everything’s all right. Duane says, “Hey man, how’ve you been?” And we say, “Great”. And then we all get together and play, and everything’s alright again.

‘That dream probably kept me sane. Until I could realize what happened. That was about three years later.’

The next album, Eat A Peach (a Duane-ism for any interviewer’s question about what the band doing to end the Vietnam War), was a huge success. But death, like popularity, would continue to find the band. Bassist Oakley was just shaking off a year-long depression over Duane, when he too was killed in a motorcycle collision just a few blocks away from the scene of that previous death. He was buried near Duane at Macon’s Rose Hill Cemetery.

As the band’s concert and album sales continued to mount, the leadership role fell to Duane’s younger brother, Gregg. The somewhat shy and quieter brother improved his singing, deepened his songwriting, and added a keyboard player to work on the next album, Brothers And Sisters. Typically, the group downed their sorrow with more hard work. ‘Ramblin’ Man’ became their biggest single ever and the group made the cover of Newsweek. In a music industry eager to follow trends, the door swung wide open for southern rock.

Few of the Allman Brothers Band members have had an easy time in recent years. After leading the band through their most difficult albums, Gregg Allman briefly married Cher and had the unfortunate experience of living in a spotlight of gossip. He bought cars at will, admitted to kicking cocaine and heroin habits, and raised hundreds of thousands of dollars in fund-raising events for Jimmy Carter.

The band broke up for a time during the late seventies, when Gregg felt the need to disappear. He visited his old stomping grounds from the days of the Allman Joys, dated girls he hadn’t seen since high school, and tried to live a quiet life. It lasted less than a year. A call came in from Dickey Betts, and Gregg Allman was ready to return.

The Allman Brothers Band reunited in 1979 with several new members, and powerful albums continued. The group still tours regularly, and in every show, according to Butch Trucks, ‘we have a place in our set that’s for Duane. We all know where it is, and I’m sure he does too.’

I was driving around recently, when I heard a radio interview with Gregg Allman. He seemed sharp and funny, but he also sounded like he’d lived a couple of lifetimes in his nearly 40 years. The interviewer asked him how he reflected on the difficulty of losing his brother, the great Duane Allman. ‘As a kid,’ Gregg said in reply, ‘I always thought an entertainer or a musician would have no bad days. How could they? They’re entertainers. They have fun for a living. Well, baby, I’m here to tell you they do have bad days.’ Allman laughed. ‘But it ain’t nothing I won’t feel better about when I’m up on stage tonight.’

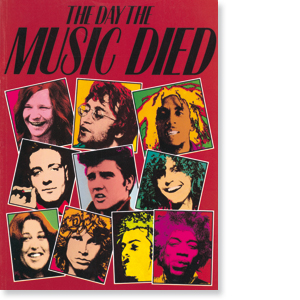

Courtesy of The Day The Music Died – Plexus Publishing Limited – Cameron Crowe – 1989