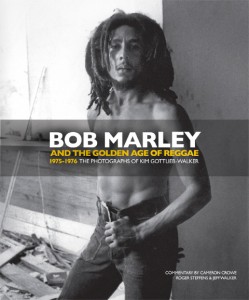

Bob Marley and the Golden Age of Reggae

Foreword by Cameron Crowe

In my journeys as a fledging rock journalist, just out of high school, I one day found myself on the phone with a cool-sounding dude from LA.

Jeff Walker was a fellow journalist and a publicist too. He easily negotiated both sides of the media coin. He was a music writer with a day-job in publicity — a job that sometimes had him acting as a conduit in setting up interviews for a firm called Rogers and Cowan. Jeff had arranged for me to interview Jim Croce on the artist’s tour stop in San Diego. The interview had gone well. Croce had snuck me past security, and we”d talked for a local underground paper, The San Diego Door, with me hidden in the dressing room of a 21-and-over club (I was 15). I promptly skipped high school the next day to hang with Croce and his guitarist, Marty, by their hotel pool. This was certainly the life. I couldn’t wait to tell Jeff. In Jeff Walker, I had a compadre on the path of documenting our musical heroes. He was like a slightly older brother, one grade ahead of me, but with the same influences and references. Jeff liked authenticity in his favorite music, especially great songwriting, and we both savored interviews with the artists who specialized in these areas. Later, when Jeff was appointed music editor of a magazine called Music World, our friendship expanded professionally too. Walker was the most excited and knowledgeable editor I”d ever worked with. He always took my post-interview phone calls in a flash, with a “How did it go?!!!?”

Our conversations about the questions, the interviews, and the nuances of both could stretch for hours. He pushed me to dig deeper, and dig deeper I did. Jeff was often first to point me in important new directions. He was the first guy to tell me about Nick Drake, or an obscure English folk band, or to delightfully load me with writing assignments that would send me in some amazing directions.

One day I mentioned to him that I’d gotten the assignment to do a “bio” on Gram Parsons, a then little-known new solo artist and former member of The Byrds and The Flying Burrito Brothers. (A “bio” was a two-page summary of an artist”s career, commissioned by the record company and sent out to the press with no by-line. It was an anonymous and easy way for a freelancer to pick up a hundred dollars and stay afloat.) Jeff nearly jumped out of his skin. He spoke excitedly about the value of this upcoming interview, the importance of Gram Parsons, and Parsons’ seminal instinct to combine a love of (then slightly uncool) country stars like Merle Haggard and Buck Owens with a powerful knowledge of rock pop. Parsons’ passionate experiment had quietly fueled the Rolling Stones “Wild Horses” and also helped inspire a wave of country-rock bands like Poco and of course, The Eagles. (To their credit, The Eagles are still passionate about singling out Parsons as the prime pathfinder to their gargantuan success. Their early song “My Man” is dedicated to Gram and his influence.)

Jeff loaded me up with an extra assignment on Parsons for Music World, and also arranged for his wife, the extraordinary artist and photographer Kim Gottlieb, to accompany me on the interview with Gram. I remember Jeff showing me some photos Kim had taken of Jimi Hendrix. I was floored. Kim’s talent in slipping past the trappings of an artist”s stardom were instantly obvious. It was all there in her series on Hendrix. Her camera reflected her own spirit, warm and loving and the results were striking. For once, Hendrix didn”t look vaguely suspicious of the camera or the photographer. Suddenly he was no longer the most exotic animal at the zoo, photographed through the bars of a pop culture cage. Here was a shot of the artist himself, at ease, with a full and open heart.

Our interview at Gram Parsons’ tour-manager’s house in Encino turned out to be historic. Parsons was a soft-voiced Southern charmer. He was starting a rehearsal for his first solo tour and band equipment was set up in the ramshackle living room. Kim, artfully adjusting her hair around the straps of the camera bags and equipment she was carrying, set about photographing Parsons with ease and familiarity. It was one of the few in-depth interviews the artist had ever given, and at one point in the proceedings, the singer-songwriter-guitarist, adorned in a floppy hat, took me aside and shared some information. He was expecting one more musician, he said with a sparkle. He’d seen her in a club. She was a young girl from DC he wanted to try out as a singer in his solo band. He clearly had a crush on her. “She’s got the greatest name,” he confided. He paused importantly. “Emmylou Harris.”

Harris showed up a few hours later, straight from the airport, radiating a beautiful combination of nerves and anticipation, and holding her guitar-case like a schoolgirl holding a copy of Franny and Zooey. And then she began to sing. Her voice gave us all shivers. As Parsons guided her through a version of an old Byrds song, “I’d Probably Feel A Whole Lot Better,” the two sang facing each other and we all shared a look or two or ten. The whole room tilted their way. I secretly pressed the “on” button of my tape recorder now hidden in my orange canvas bag. (The tape is a bit muffled, the microphone was hidden in the orange bag too.) It was an afternoon of quiet lightning, and we all felt it.

It was also a remarkable glimpse of Kim’s style. Life unfolded and she quietly caught the highlights. Gram and Emmylou’s budding love affair, the looks between them, and Parsons shy crush… it’s all there in Kim’s photos. Kim’s supportive and soulful sensibility always led her to know exactly where to be with her camera. I watched her quietly work alongside the heartbeat of the music and the emotions in the room. Always a fan, always an assistant to the groove, Kim is a joyful audience as well as a documentarian. Her style is simple. Listen…snap… snap… listen… snap…. listen. It’s no surprise that her work never interrupts, only inspires and celebrates the creative flow she’s there to capture. Though it’s said elsewhere in the wonderful collection of her work that you are now holding, it bears repeating — her proofsheets are surprisingly economical. She is not a blitzclicker, she is a collector of fine moments. And when Parsons died less than three months after our afternoon session, Kim’s photos from that day became one of the few surviving documents of Parsons and his short, now-legendary life and career. And Emmylou Harris is still singing about that musical love affair that changed their lives.

My friendship with Jeff and Kim flourished in the years to come. Along with our endless pow-wows about music, the sharing of craft and anecdotes, facts and records and songs and photos, I also had the benefit of watching how a truly dedicated relationship worked. Their son, Orion, was a perfect romantic collaboration. I watched these young parents, Jeff and Kim, raise their son with the same passion and artistry they brought to their love of music. Their instincts were something to behold. Ry grew up with all the music we loved. And it was right about this time that Jeff and Kim began talking about a new kind of music, a wave of songs and culture coming from Jamaica. It was the future, Jeff said, and it was as important as Dylan to the generation just before us. He was talking about ska, and reggae and dub… and a group he called “The Beatles of Jamaica” — Bob Marley and the Wailers.

Jeff was now working as a publicist with Island Records, and he’d visited Jamaica, walked the mean and soulful streets, and hung out with Marley. Kim had been there too. It was Kim who was the first “outsider” to photograph Marley and the young Jamaican masters around him, wildly creative artists who had previously seen a camera only as the wicked tools of tourists. Her photos would soon fill the walls of record stores and clubs around the island.

There was something special in Jeff and Kim’s early conversations about this growing musical movement. They were positively giddy, but also reverent. The music was more than a commercial enterprise for these reggae artists, the Walkers stressed, it was a lifestyle and a faith. It was about culture, and the rhythm and roots of the rastafari movement. Marley’s charismatic power was rooted in something more than a pursuit of simple success. It was a mission and a passion, and though Marley, with his rock star looks and universal melodies, was the reigning star of the island… the key to the movement was also in the often mysterious and mystical group of players who surrounded, played and competed with him.

As part of Jeff and Kim’s attempts to spread the word about reggae, and to prepare for the release of the Wailers’ Rastaman Vibration album, Jeff had taken a few journalists over to Kingston to meet and interview Marley. The great Lester Bangs was one of the first writers to visit, and Lester’s trademark piece about the experience is also discussed elsewhere in this collection. I was in the next group. This was a smaller touring party — just us — Jeff and Kim and Ry and me. It was a family adventure, with a mission attached. Together we would further explore Jamaican culture, and the intricacies of the relationships Jeff and Kim had forged in their previous visits. With Jeff and Kim as tour guides, we worked our way through the Kingston music scene. Our trip would center around an interview with Bob Marley, of course, but there were many other musicians to track down. I had prepared especially well for Marley, who was often verbally elusive (as Bangs captures brilliantly in his piece), and discussed his work in a thick Jamaican patois filled with passion but little concrete information about his craft and methods. But this much was clear before we even began our journey, the island was bubbling with scores of characters as deep and colorful as the music itself. And with Jeff and Kim’s help, I would interview as many of them as I could.

It has often been noted that only Motown Records in the 1960s could rival the plethora of street anthems and the sheer volume of local hits that came out of this small island in the late 1960s and early 70s. That explosion was in full evidence in the heady days of our 1976 trip. Thanks to Jeff and Kim’s encouragement and my early assignments for Music World, I”d also found my way into Rolling Stone magazine. They too were ready for my reports from Jamaica. So. Armed with a bunch of assignments, and a spanking new professional Uher stereo-cassette recorder in a leather case, off we traveled to the land of dub.

Courtesy of Titan Books – Cameron Crowe – November, 2010