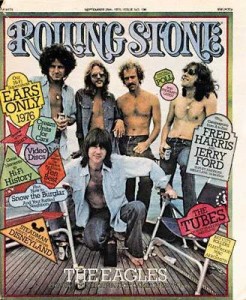

The Eagles: Rolling Stone ’75

With the recent release of History of the Eagles on Blu-ray and DVD, it made sense to revisit Cameron’s Rolling Stone cover story from September, 1975.

Cameron delves into the band’s formation, their tumultuous recording history with Glyn Johns, their label woes, Irving Azoff and much more. It’s an interesting snapshot of the band in their mid to late 20’s up to their release of One of These Nights.

The Eagles: Chips off the old Buffalo

Perched on the million-dollar border between boredom and laidbackness, the Eagles perceive a hardening of the artistry and the industry.

Hiya! This is superjock Larry Lujack! Sitting with me right now in the Super CFL Studios-straight from California-are everybody’s favorite hitmakers…those darn Eagles! In town for two concerts at the Arie Crown Theatre, the band is visiting one of Chicago’s top jocks to play, for the first time, the title track and single from One of These Nights.

“How ya doin’, guys?” Lujack winks. It is guitarist/vocalist Glenn Frey, a long-time Johnny Carson aficionado whose streetwise L.A. drawl stands out from the groggy “okays” and “alrights” of the other four Eagles. “Doin’ real fine, Larry,” he says from behind reflector shades. “It’s nice to be here at WCFL this morning.”

Lujack, a world-weary Jack Nicholson look-alike, doesn’t miss a beat: “Let’s talk a little bit, guys, about how you got together.”

“Glenn and I used to play for Linda Ronstadt and…”

Lujack cuts drummer Don Henley short. “Linda Ronstadt.” The name rolls off his lips with lecherous abandon. “She’s probably my favorite chick singer, heh-heh. Say, I remember reading somewhere that the Eagles do the best ‘ooo’s in the business. What do you say to that?”

” ‘ooo’s for bucks, Larry, that’s our motto.” Frey flashes a sly grin. “The only difference between boring and laid back is a million dollars.”

Lujack chortles mirthlessly. “You rock & rollers are all alike, aren’t you? Hey, is it true you guys want to sound like Al Green? What’s the matter, you tired of being cowboys?”

“That’s actually very true,” Henley deadpans. “We almost called this record Black in the Saddle….”

Lujack throws a hand signal to his engineer. Okay. For the first time ever, let’s listen to that new Eagles record – ‘One of These Nights!’ Alllriiiiiight!!!” Safely off mike, “Superjock” heaves a booming sigh. “That was a fuckin’ great interview,” he snickers. “Now who’s got the drugs?” A few courtesy chuckles later-heh-heh and all that-the Eagles have eased out of the building.

It had been an anticlimax, to be sure, but this was still a prize moment for Frey, Henley, bassist Randy Meisner and guitarists Bernie Leadon and Don Felder. After six months of work and anguish, their fourth album, One of These Nights, was finally public.

If only for perfectly capturing the feel of L.A., the Eagles are the one band that’s carried on the spirit of the Buffalo Springfield.

– Neil Young ’75

The view from the Los Angeles hills offers a romantic and soul-searching look at Hollywood’s neon glow. It’s not surprising that much of One of These Nights was written under its influence. The picture is hypnotic. In the few months that Don Henley and Glenn Frey have lived here – strictly for proximity’s sake, they say – the two have spent many nights staring out at the “million dollar view” from their living room table and jotting down bursts of songs. Now, just one week before the band will reenter Criteria Sound Studios to record vocals and finish the album, the entire house is littered with yellow legal tablets – all of them scribbled black with abandoned or half-finished verses. “It’s finals week,” says Frey. “We’re cramming.”

The Eagles have always approached their albums cautiously. Every word and melody is considered and reconsidered before a song is deemed recordable. In the studio, the process repeats itself. “Sometimes I wonder if we don’t take ourselves too seriously,” Henley muses after hearing the Beatles’ nonsense song “You Know My Name (Look Up My Number)” on his car radio. “Who knows, maybe Art is just a dog on Neil Young’s porch. Every time I start writing one of those wonderfully sensitive songs that we write, I start wondering, ‘Who really gives a shit? Do I really give a shit? I want to do something semihumorous on one of these records someday. Something that doesn’t demand so much fuckin’ time and energy. We’ve never had an easy time making Eagles albums.” This one, the follow-up to On the Border (which included “Best of My Love”), has been no reprieve. Bernie Leadon complains, “It seems to take more time and effort every year to forget the whole trip of touring and recording and get loose enough so that the creative juices flow naturally.” Frey and Henley, in fact, already have a suggestion for a story on the Eagles: “The Hardening of the Artistry.”

Don Henley sits alone at the table tonight. He looks like he could be a better-looking younger brother of Mac Davis. Headphones clamped over his curls, he’s sworn himself to finish the lyric to a basic track titled “After the Thrill is Gone,” or as he’d named it earlier, “Here’s Another Hidden Commentary on the Music Business Disguised as a Love Song.” On a cluttered oak slab before him lie all the accumulated vestiges of life as an Eagle: cassettes of outtakes, guitar picks, songbooks, gold record receipts, an Elektra/Asylum yo-yo, a copy of Timemagazine’s Cher cover with a SO WHAT sticker pasted over the banner and, of course, stacks of legal tablets.

In the next room, Frey is absorbed in a basketball game on TV. Chain-smoking and drinking Dos Equis, he rumbles the house with beery cries of “Willya stop the son-of-a-bitch” and “Turg-o-vitch!!” After a while, Henley rips off the headphones and heads for the TV room in disgust, adding a new tablet to the heap. This one is blank except for two lines.

What can you do when your dreams come true

and it’s not quite what you planned

“Naw, naw, naw….” The game’s about over and, faced with another night at the legal pads, Frey and Henley are warming to the idea of a conversation. “There’s no way it’s stopped being fun, it’s just…harder,” says Frey. “The main reason it’s taking us longer to do every album is you just don’t have the kind of time to collect ideas. You usually have about 20 years to work on your first album, then the media turns back around in six months and wants more. And if you’ve mastered a little bit of the language, your success formula tempts you every time you use it again.”

“Plus,” Henley continues, “it’s not just a high-school game anymore. It’s a fucking business. An occupation. It’s a profession. And it’s fuckin’ hard. I’m sure nine-to-five is just as trying, but their one advantage is that they can leave it at the office. This is a 24-hour-a-day trip. It’s like cramming 60 years into 28. Or, as Joe Walsh says so brilliantly, ‘You burn the candle at two ends/Twice the light in half the time.’ I don’t know, at least we’re doing what we want to be doing.”

Frey: “But that gets boring and unfulfilling too. There are days when I drive to the office, drink a cup of coffee for an hour, check the mail, watch Irving [manager Irving Azoff] kill on the phone, get existential anxiety, go to the Cock ‘n Bull to eat, drive to the dry cleaners, drive back up to the house, roll a joint, look out at the view and wonder what’s gonna get me up to do what I want to do. That’s the whole premise of ‘After the Thrill Is Gone.’ Where is the next stimulation?”

Henley: “Where is the next dream now that you’ve got this one? We were talking about this with Clive Davis the other night and he said something that’s really stuck with me. Once you get comfortable, once you get most of the things you’ve always wanted, your universe becomes defined into a little square. Eventually you get to where you don’t know what the fuck’s going on outside your own little rectangle. It’s like, I got up the other day and took my slide projector in to get worked on, got my camera repaired, had the car washed, got my cassette player fixed.” He shrugs. “Took up the whole day.”

“Servants is the answer! Frey shouts, as if suddenly enlightened. “We should call up Abbey Rents and find someone to live for us.” He pauses a moment, then turns serious. “You know that adage, ‘For every dream come true, there’s a curse’? One of those curses is just a lifestyle…it’s going on all the time. When I take a look at the last year, between On the Borderand this album, what have I done? Worked my ass off. You know, we went on the road, got crazy, got drunk, got high, had girls, played music and made money. If you don’t watch it, that can become your whole life.”

Glenn Frey, 26, and Don Henley, 28, through their crisp, quotable lyrics and interviews, are chiefly responsible for creating what one band member calls “our punky James Dean image.” As a result, most journalists rarely bother to explore the band’s remaining three-fifths. They would learn that for Bernie Leadon, Randy Meisner and Don Felder – all comfortably settled into secluded home and road lives – the Eagles are not quite a “24-hour-a-day trip.”

Says Felder, 27, who’s planning to move out of Topanga Canyon and up the coast, “I’m glad that Don and Glenn project a lot of the band’s L.A./Hollywood charisma. Every group needs one and in this band we’ve got two people doing that. Even though Glenn’s from Detroit and Don’s from Texas, they really know and live the L.A. scene. It’s real. It suits their personalities. Personally, I don’t feel comfortable living there. I don’t relate to it at all. I’d rather be alone with Susan [his wife] and Jessie [their year-and-a-half-old son].”

Nebraskan Randy Meisner, 29, is by far the most subdued of the Eagles. On his time away from the band he is with his wife Jennifer and three children, Eric, Heather and Dana, in Mitchell, Nebraska.

Meisner, too, is content to leave the posturing to Frey and Henley – but not without reservation. “No, I don’t go along with everything they say or do. For example, I’m probably the only one in the band who loves funky rock & roll, trashy music and R&B. And I don’t agree with some of our images either. But Don and Glenn have it covered. I guess I’m just very shy and nervous about putting myself on the line. They’re used to doing that.”

Twenty-eight-year-old Bernie Leadon, the only true Southern Californian in the band, cherishes the easy anonymity of his Topanga lifestyle. He strikes one as a commercially successful musician with a purist’s guilty conscience. He admits to twice leaving and rejoining the Eagles. His previous bands were Flying Burrito Brothers and Dillard and Clark, both critically raved and financially starved.

“My attitude toward the band is pretty good these days. We’ve all grown a lot. Everybody realizes this is a good opportunity to get some bucks ahead and also, man, I think the music is worth something. There’s so much bullshit in the pop world. So much of it is just lower-chakra music. No finesse. It’s just sexually oriented. That’s a form of escape. I like to think our band is more than that. That there’s some thought, some living behind it. In the meantime, I just don’t want to succumb to the comforts of an affluent society and say, ‘Okay, this is swell, I give in.’”

Leadon, given to T-shirts and jeans, thinks concerts have been reduced to “business transactions.” And he despises limousines: “It feels like you’re thumbing your nose at your audience.” He succumbs and rides the limos but escapes to the beach whenever he can. “To me, sun and salt water is where it’s at. That, a little wine, a little music and my old lady…that’s it. That’s all that matters.”

Glenn Frey glibly writes off these crosscurrents of personalities, lifestyles and directions as the Eagles’ vital force-creation tension. “We’re the Oakland A’s of rock & roll,” he says. “On the field, we can’t be beat. But in the clubhouse, well, that’s another story. Sure, Don and I are a lot more into it than the others. We’re completely different people. We rarely even hang out together.

“Sometimes I wonder if the other guys in the band know how much I like them. How much of a foundation they are. We never even talk about it. We each have our own spaces. We play sometimes and we fight sometimes. I get so caught up in all this-the pressures of being Glenn Frey of the Eagles, the guy who talks a lot-that if Randy or Bernie needed some confidence building, I might be too self-involved to realize it. I worry about that. But even though there’s a keg of dynamite that’s always sitting there, this band is fairly together.”

Frey is on the edge of his seat now, eager to make his point. “I just figure we can’t lose. The longer the Eagles stay together, the better it’s gonna be. No matter what. We never expected to get this far, anyway. I thought we’d break up after our first album.”

Still, there is a predestined aura about their success, a feeling that maybe even the tension was plotted. On stage they wear their recently obtained superstar status with the nonchalance of a band always geared to go all the way.

The story begins in Detroit, where a sunken-eyed, girl-crazy guitar player named Glenn Frey began popping up in various local bands like the Mushrooms, the Subterraneans and the Four of Us. “He knew he was cool. He was really into this whole role of being a teen king,” one girl remembers him. “He took my sister out once and tried to feel her up. She didn’t let him, so he brought her home early and never called her again.” At the time, his mother had another theory. “Glenn,” she remembers telling him, “your life revolves around groups of people. You can’t relate that well to individuals. If your guitar had tits and an ass, you’d never date another girl.” Frey smiles. “That was really true,” he says. “I’ve had long talks about that with her since.”

These days, Glenn is anxious to play down his jack-rabbit adolescence. “I read something that really made me think. It was an interview Jules Feiffer did for – oddly enough – Playboy. He said, ‘Remember when you were 11 years old and girls were a drag. The only thing that was cool was playing Army and recess and dodge ball. The big mistake that men make is that when they turn 13 or 14, and all of a sudden they’ve reached puberty, they believe that they like women. Actually, you’re just horny. It doesn’t mean that you like women any more at 21 than you did at ten.’ That’s strong shit. I read that and though of all the guys I’ve heard say, ‘I fucked the shit out of her.’ It made me realize that the real test for a man is learning to respect and like women.” Frey’s on-the-road womanizing days are over, he believes. “I want to settle down,” he says. “A whole lot.”

After a brief apprenticeship with Bob Seger (Frey sang backup on “Ramblin’ Gamblin’ Man”), Glenn left college and made his big move to L.A. Why not New York, which was closer? “Well, the truth was that I was gonna buy drugs in Mexico and see a girlfriend who’d moved out here with her sister. My parents told me that if I was going to California, they weren’t gonna give me a goddamn dime. They would send me five bucks/ten bucks in every letter. ‘Buy yourself a nice breakfast and a pack of cigarettes.’ I send them money now. That’s the big get-off about money. Doing things for other people. I’m paying for my brother’s college education.

“But anyway, the whole vibe of L.A. hit me right off. The first day I got to L.A., I saw David Crosby sitting on the steps of the Country Store in Laurel Canyon, wearing the same hat and green leather bat cape he had on for Turn! Turn! Turn! To me, that was an omen. I immediately met J.D. Souther, who was going with my girlfriend’s sister, and we really hit it off. It was definitely me and him against whatever else was going on.”

Souther and Frey formed a duo, Longbranch Pennywhistle, and recorded an album on Amos Records. Eventually they split up with their girlfriends and, on the advice of Jackson Browne, moved into his $60-a-month upstairs apartment in Echo Park. “So the three of us were all living there, listening to records or to Jackson. I’d just lay in bed and hear him practice downstairs. The piano was right below my bed. Those were great times.

“Then one day J.D. and I got in a fight with our record company and suddenly we couldn’t make any more records. Every day we’d go to the office, ask if we could get released from our contracts and they’d say no, so we’d go down to the Troubadour bar and get drunk. The Troubadour, man, was and always will be full of tragic fucking characters. Has-beens and hopefuls. Sure, it’s brought a lot of music to people, but it’s also infested with spiritual parasites who will rob you of your precious artistic energy. I was always worried about going down there because I thought people would think I had nothing better to do. Which was true.”

Don Henley, lead drummer and lead singer in a band named Shiloh (also on Amos Records), never spoke to Frey when they saw each other in the bar. “I just thought Glenn was another fucked up little punk.” Henley had also just made his move out to L.A. Behind hem were four years of college and Lindon, a Texas town (population 2000) where he was the weird hippie. “In a town that size,” he says, “all you can do is dream. I had this one English teacher who really turned my head around. He was way out of place in this little college. The bohemian, the first one I’d ever seen. He’d come to class in these outrageous clothes and lecture cross-legged on top of his desk. One day he told me, ‘Your parents are asking what your future career plans are. I know there’s a lot of pressure on you to decide.’ Then he said something I never forgot. ‘Frankly, if it takes you your whole fucking life to find out what it is you want to do, you should take it. It’s the journey that counts, not the end of it. That’s when it’s all over.’” And Don was off. His mother and dying father not only wished him well but supported him in his first year of scuffling.

Frey was first to break into one of Hollywood’s royal rock circles: “I had just played a couple of songs for David Geffen, the guy who managed Joni and CSNY-the people I wanted to be with,” he recalls. “Geffen told me point blank that I shouldn’t make a record by myself and that maybe I should join a band. Then Linda Ronstadt hired me. It was two days before rehearsal was supposed to start and they still hadn’t found a drummer. And here was Henley, just standing right up in the Troubadour. So I struck up a conversation with him. I told him my whole trip was just stalled. I had all these songs and couldn’t make a record and I wanted to put together a band, but I was going on the road with Linda. Henley said that he was fucked up too. Al Perkins had left Shiloh to join the Burritos and…we were both at impasses. So he joined Linda’s group too. The first night of our tour, we decided to start a band.”

But not just another L.A. band. “We had it all planned. We’d watched bands like Poco and the Burrito Brothers lose their initial momentum. We were determined not to make the same mistakes. This was gonna be our best shot. Everybody had to look good, sing good, play good and write good. We wanted it all. Peer respect. AM and FM success. Number One singles and albums, great music and a lot of money.

“Money,” Henley reasons, “was a much saner goal than adoration. They’ll both drive you crazy but if I’m gonna blow my brains out for five years, I want something to show for it.”

John Boylan, Linda Ronstadt’s manager/producer, was the first to come up with the combination of Frey, Henley, Meisner and Leadon. His idea was to form a five-piece supergroup to back Linda. “We all thought, ‘Yeah, great, but why don’t we just put together a supergroup to back each other up,’” says Don. “John and Linda gave us our blessing. I really respect Linda Ronstadt. She’s got a good heart. She’s never been selfish enough to hold anybody back.”

Frey, now with the Eagles, made his triumphant return to David Geffen’s office without even a demo tape. As the group’s father figure/leader in its first year, Bernie did all the talking. “Geffen had no idea what we sounded like,” Henley recounts. “And here comes Bernie walking in saying, ‘Okay, here we are. Do you want us or not.’ It was a great moment. Geffen kinda said, ‘Well…yeah.’ A lot of credit has to go to Jackson, who convinced David we were good. Geffen himself couldn’t carry a tune in an armored car. Still, he kept us alive while we got some songs together and rehearsed by playing four sets a night in a club in Aspen.” The music was rocking blues and their show included Sonny Boy Williamson’s “Pontiac Blues” and an R&B-tinged version of “Take it Easy,” Jackson Browne’s song from the Echo Park days. Geffen eased Frey out of his contract and fronted the band $125,000 and they went to London to record their first album for Asylum Records, produced by Glyn Johns.

It was Johns who reshaped this bar band into “the country-rock band with those high-flyin’ harmonies,” as their bios kept saying. “He was the key to our success in a lot of ways,” Glenn admits. “He’d been working with all these classic English rock & roll bands…the Who, the Stones…he didn’t want to hear us squashing out Chuck Berry licks. I didn’t mind him pointing us in a certain direction. We just didn’t want to make another limp-wristed L.A. country-rock record. They were all too smooth and glassy. We wanted a tougher sound.”

By all accounts, Johns, known as a kind of a school-marm in the studios, led the Eagles by the nose through their first album, camp-counselor style.

“Glyn made us very aware of all the little personal trips within the band,” says Henley. “He’d just stare at you with his big, strong, burning blue eyes and confront you with the man-to-man talk. You couldn’t help but get emotional. We even cried a couple times….”

Frey: “He’d say, ‘You’re a fine singer, a fine guitar player, a great asset to this band….’”

Henley: “‘But you’re being an asshole.’”

One of Johns’s strictest studio rules-no drugs-held fast. “It really irritated him,” says Frey, “that Randy and I would sneak off and smoke weed. He’d tell me, ‘You smoke grass and then you don’t say what’s on your mind when it comes to mind. Now it’s a week later and you’re talking about something that you should have ironed out seven days ago. And that’s juvenile…’ What can you say? You’re busted. It’s true. He pointed out a lot of bad habits in everybody. It’s hard to be friends with someone who does that to you. It’s like a basic premise for friendship is that you accept the threat that everybody else poses to you.”

If Eagles was the perfect attention getter (it produced three hit singles, “Take it Easy,” “Witchy Woman” and “Peaceful Easy Feeling”), Desperadoestablished the Eagles’ credibility. The album’s low-key concept, that the rock & roll life is not unlike an outlaw’s, was an idea Henley, Frey, Browne, Souther and Ned Doheny had kicked around for years. Even today, they pipe dream about a screen adaptation.

Though the Eagles agree that it’s probably their finest effort, Desperado was the scene of the battle that the group still fights every time they enter the studio. “The only two people in this group who tend to think alike are Glenn and me,” explains Henley, “and we’ve always wanted every song to be the best that it could be. We didn’t want any filler. No stinkers. So there’s been plenty of fights even with Glyn Johns over ‘Aww, you guys just want to rewrite all the lyrics.’ That’s not true. We don’t disagree with anything anybody in the band has to say, it’s just how they say it. When somebody hears a bad song, they’re not gonna say, ‘So-and-so wrote a weak song.’ They’re gonna say, ‘There’s a shitty song on the Eagles album.’ It reflects on everybody. Still, I suppose it’s a matter of taste.”

Frey cuts in, “I asked Graham Nash once, ‘In CSNY did you guys ever change any of the other guys’ lyrics?’ He said, ‘No, never. Why, do you do that?’ I said ‘yeah’ and he kinda looked shocked. I just think it’s part of the band trip. All these legal pads don’t make me feel heavy. It just makes me feel like I’ve got a lot of work to do.”

“Glenn is not a great guitar player and I’m not a great drummer,” says Henley. “On the other hand, Randy, Bernie and Felder are incredible on their instruments. We’ve just taken it upon ourselves that this is our department. Maybe we’re full of shit but I think we’ve proven ourselves. We recognize the fact that those guys have got a need to say something and if we can help them say it better, then I think everybody’s better off. It’s not a matter of credit or money or any of that stuff. We’ve been splitting the publishing evenly from the beginning.

“All the fighting reached a culmination point on On the Border. That’s when we didn’t finish the album in London with Glyn Johns. We came back with two songs, “You Never Cry like a Lover” and “Best of My Love,” and finished in L.A. with Bill [Szymczyk]. Glenn and I assumed this bulldozer attitude before we went into the studio of, ‘We ain’t gonna put up with any weaknesses. Every song’s gonna be great.’ There was a lot of fighting. Don Felder, who we just added to the band in the middle of the album, was so scared he’d joined a band that was breaking up.”

Frey and Henley, it would be safe to say, are the band’s primary students of the music business. They devour all the trade magazines, reading sales figures and interview features like most businessmen read Wall Street Journal. “You can’t be sensitive artiste all the time,” says Henley. “You have to be able to fend for yourself. I don’t want to be like the Fifties superstars, walking around now completely broke and trying to make a comeback.” Henley and Frey were also the main engineers behind the band’s leaving Geffen-Roberts management in favor of Irving Azoff, himself a former employee of Geffen and Elliott Roberts.

“It’s the old sauna story,” says Henley. “Jackson, J.D., Ned and Glenn were at David Geffen’s house just down the street one day and he said, ‘I want to keep Asylum Records really small. I’ll never have more artists than I can fit in this sauna.’ Then, all of a sudden, he was just signing people right and left.

“Then Geffen just split the management scene entirely and became a record company president, turning the whole thing over to Elliott Roberts and John Hartmann. It wasn’t the same after that. Elliott’s insights were great, but he’s been through all that stuff with Joni and Neil and Crosby and all those guys. Finding the right manager is kinda like finding the right girl. When you finally get the perfect one, you want the one that’s your own age and has been through the same trip you have. We were always the young guys down there. Nobody paid much attention to us. We found out our management company had signed Poco and America by reading Melody Maker.”

Azoff, 26, formed his own management firm, Frontline, at the insistence of the Eagles and two other artists he had developed a close relationship with, Joe Walsh and Dan Fogelberg. Azoff, referred to by the Eagles as “your shortness” (he’s 5’3″), has acquired a reputation of sorts because of his showboat business methods. “I think it’s great to have someone pounding on record company desks saying, ‘Fuck you, you’re not getting another Eagles album,’” says Frey. “When we first met Irving, we had two gold records and $2500 in the bank. Now we each make a half-million dollars every year and see every penny.

“Getting Irving was like catching Geffen on the upswing six years ago.” Sure enough, Azoff, along with Fogelberg and Walsh, has already put together his own label, Full Moon, on Epic. An affiliation with Jerry Weintraub, the concert promoter/manager of John Denver, Moody Blues and Frank Sinatra, is in the works. But, he says, “managing the Eagles will always be my top priority. Always.”

Asked about the present Eagles game plan, Don Henley plucks up an acoustic guitar and strums absentmindedly. “We definitely believe in maintaining the underdog status,” he decides.

Frey is slowly, deliberately nodding his head. “Mass appeal is definitely suspect. Just look at our Grammy winners, Stevie Wonder excluded. Sometimes all that mass appeal means is that you simplified your equation down to the lowest common denominator. It’s a great temptation to think, ‘Well, fuck it, they’ll buy this. No one ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the mass public.’ Bless H.L. Mencken’s heart. He’s absolutely right but, see, I don’t want that kind of karma. That must be weird shit, to sell a bunch of records and make a bunch of money off something that didn’t mean a fuckin’ thing. I don’t ever want to face that.”

Henley: “It’s not a sin to be in the top 40. Look at Paul Simon and Joni. They sell millions of records.”

Frey: “I’m looking to Joni and Paul Simon and Randy Newman as living proof to us that you can still be doing it in your 30s. I get my confidence by watching them. I realize I can still do it when I’m 32, if I keep my perspective. If I don’t overamp and die from success poisoning. This business is like walking through a mine field. That’s why people who envy me look foolish. They don’t see me at the Record Plant, trying all night to get one vocal. As far as they know, I’m just a guy who’s drunk down in Tana’s one night a week.

“I’m beginning to feel kind of proud that we’ve gone through three albums,” says Henley. “I’m beginning to feel like a trooper, like we’ve finally got a place in the big rock pile, as it were. The important question now, though, is will we make a better album than the last one. Knowing full well that, whatever we do, it’ll be gold in three or four weeks.”

There is a reflective silence around the table, as if Henley has struck the quick of the matter. Frey finishes the last of his beer and set the bottle down with a loud clunk. “Well, you can clock me in at 5 a.m.” He squints at his watch. “Good night.”

The Eagles return from a record crowd at the Chicago Stadium to find their Holiday Inn’s front desk covered with phone messages, telegrams and flowers. With One of These Nights in its fifth week at the top of Billboard‘s LP chart, the group has just won in Best Song (“Best of My Love”) and Best Group (over Led Zeppelin, Elton John and the Rolling Stones) categories of the nationally televised Rock Awards. On the phone upstairs with Glenn Frey is Joe Walsh, who accepted the awards for them, and, in the process, kissed presenter Raquel Welch.

“You really kissed her,” Glenn is demanding, eyes wide. “Did you ask her about the silicone?” He spots the writer going for his notebook. “Naw, naw, naw. Don’t use that. That’s a cruel remark. Besides, we can’t be roguish underdogs anymore.” Frey grins and flips a cigarette into his mouth. “We have to be gracious winners.”

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #196 – Cameron Crowe – September 25, 1975