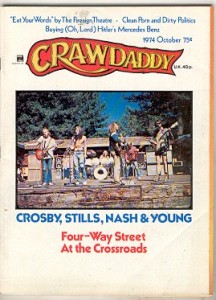

Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young – Crawdaddy Magazine

Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young Carry On

Crosby looks more like Bozo the Clown every day .Nash still binds them together. Young cruises the amps, and Stills has undergone a major transformation. Backstage there’s lots of backslapping and hugging; it’s healthy, but fragile. Will it hold up?

“Do I think CSNY will ever reform?” Stephen Stills crouched over a pool table in a room directly above Jim Guercio’s Caribou Ranch studio and lined up his shot. “I don’t know, man. We tried to do an album in Hawaii last summer and it fell apart. Caused everybody a lot of grief. I’d prefer not to get into the details, though. that gets into my judgements, my opinions . . . it wouldn’t really be fair to discuss them. I showed up to play . . . and one day we stopped playing. I just don’t know. I don’t want to talk about how incredibly famous we are or how we could set the world on fire if we got back together. I want to play. I want to sing. I want to make good records. And if that doesn’t happen, I’m gone.” Stills paused to listen to the rough mixes of his As I Come of Age solo album filtering through the floorboards, then pumped the cue stick. “Nine ball, side pocket.”

Stills spoke of entering “the happiest times of my life.” His marriage to French singer-songwriter Veronique Sanson was about to produce a child and the new band Stills had assembled for his first post-Manassas tour was functioning flawlessly in rehearsals. It was Spring and everything was falling into place for the embattled guitarist and he flaunted that self-assurance.

“I’ve done it all. All of it,” Stills insisted. It seemed almost a penitent’s pride. “I’ve been the most obnoxious, arrogant superstar to walk the streets of Hollywood . . . I’m still arrogant. I can be an absolute bastard. I have a bad habit of stating things pretty bluntly. I’m not known for my tact. But look, I can see that I really got carried away with myself. Being a rich man at twenty-five is sometimes difficult to deal with . . . you make mistakes. I’ve made all of ’em. But I’m thirty now and at this point it’s all very funny.

“Ever since I got married, life is just a gas. This tour should be incredible. Joni Mitchell and I had a great discussion about that a couple of weeks ago. I’m basically a blues singer and blues singers are supposed to suffer. I almost feel guilty. I’m trying harder than I have in years. I’m determined to do the best I can. I want to be good.”

On that solo tour Stephen Stills was indeed at his finest. The group was small enough to keep Stills out front and working rather than hidden behind a wall-of-sound; and efficient enough to bring out the best in him. The biggest surprise, however, came at the tour’s mid-point when he boasted from the stage in Chicago that plans had just been finalized for a summer-long Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young tour. A studio album, he told the euphoric crowd, would follow in the late Fall . . .

***

Several months later, a bronzed, buoyant Stills sat in CSNY manager Elliot Roberts’ Los Angeles offices and reflected on the first three weeks of rehearsals at Neil Young’s Broken Arrow Ranch in La Honda, south of San Francisco. “Neil built a beautiful stage right across the road from his studio. We get out there in the sun and play for about four or five hours a day. We haven’t done the old tunes in years, man, it’s almost like playing them for the first time. Everybody’s a better musician. And there’s plenty of new songs too. We’ve all been writing a lot, especially Neil. It’s been tons of fun and no hassles.

“It’s amazing how it all came together so quickly. Elliot and Graham came and saw me, we started talking about it and figured it would be foolish not to give it another try. Neil and I got together and discussed it. We got along beautifully. I guess we’re pretty much the same people, just a little older and a lot wiser. And will you look at this tan? How can you lose?!”

Considering the size of the sites (averaging 50,000-plus) and the ticket prices the group chose for the tour, there was very little to lose and, according to estimates, approximately $8 million in gross to gain. Everyone involved was defensive about the motives for the reunion in the face of this tremendous cash flow.

“It’s not the money,” stressed Elliot Roberts. “Listen, they’ll do very well but if it was only the money we were after, the album and tour would have happened long ago.” As it happens, they had tried that last year and it failed. “We’re not capitalizing on this tour in the usual way. There will be no live album. It’s not being filmed – we’re not going to do any of those trips.

“There’s no doubt they’re going to make a lot of money. If the Beatles went out they’d make a lot of money. Bob [Dylan] made a lot of money. It’s the nature of the race. But I don’t think it has anything to do with why they’re going out. Neil is a rich man. Stephen’s got money, he’s been touring. Graham has plenty of money and David isn’t starving. The music’s exciting for them. They realize that the four of them together are stronger than any one of them alone.

“It’s a matter of attitudes,” Roberts continued. “They’re older and for the first time their attitude is that of professional musicians who really feel that they make incredible music. They feel that they have a commitment to play that music, that they are living up to that commitment as men.” That kind of adolescent altruism seemed a little hard to believe. “It wouldn’t work if just Neil and David wanted or needed to do it. It wouldn’t work if Stephen and Graham and I wanted to do it. It’s a combination of everybody coming to the right place in their lives at the right time.”

***

It’s a grey, rainy day in Seattle. Looking like their backcover photos on their first Buffalo Springfield album, Stephen Stills and Neil Young sit at the downtown Hilton’s rooftop restaurant chattering nervously and laughing a little too loudly over their old guitar war days. After a while, Young clams up, staring silently down at the nearby Coliseum and the massing crowds. In a little over an hour, David Crosby, Graham Nash, Stephen Stills and Neil Young will find themselves opening their first tour since the 1970 roadwork that spawned Four Way Street.

Outside the Coliseum, gangs of ticket-hungry fans prowl for a chance to crash the sold-out show. One peach-fuzzed fourteen-year-old parades his budding machismo. “Bastards,” he growls, barely out of rent-a-cop earshot. “Looks like I’m gonna have to blast of a few pig heads to get inside.” Strong words from one who hadn’t reached his tenth birthday when the first Crosby, Stills and Nash album was released in the summer of ’69.

Then, CSNY represented a sophisticated harmonic oasis amid the parching acid rock of the time. Now they are the Founding Fathers, the inspiration for the current generation of prosperous L.A. country rockers. “Hey, man,” Eagle Glenn Frey once said, “I bought that first album and freaked out right along with everyone else. Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young are, in essence, The Great American Supergroup.” And the kids, more than the fanatical original wave of fans, seem compelled to examine the sweet-singing artifacts.

Inside, one could easily venture to say that most of the audience had never seen the band in their first period of concert activity. Most likely the majority were initiated into Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young through Neil Young. And just as a Joni Mitchell concert seems to draw an abundance of willowy, mountain-fresh blondes, the males portion of tonight’s crowd is predominately clad in patched Levi’s and well-worn Pendletons, with floppy leather hats covering disheveled hair. It will take most of them, including the reviewer from a local paper, three numbers to finally recognize Neil Young behind his electric piano sporting short, slicked hair with a strict center-part that makes him look not unlike Chatsworth Osbourne Junior III from the Dobie Gillis Show.

The lights dim and CSNY – augmented by Ross Kunkel on drums, Joe Lala on congas and Tim Drummond on bass – take the stage at 9:00 with steaming “Love The One You’re With.” The 40-song set, which runs through virtually every favorite collective and individual effort, lasts until past 1:30. They are stronger than they were, practiced and intense. There are nine as-yet-unreleased tunes: David Crosby’s “Carry Me”; Still’s “First Things First,” “Bye Bye Angel,” “My Favorite Changes” and “As I Come Of Age”; and Young’s “Traces,” “Human Highway,” “Love Art Blues” (for his dog, Art, the tour mascot), “Long May You Run” (for his car, a customized Southern California Woody) and “Push It Over The End.” “Neil’s been writing three songs a day,” Stephen later confides in mock fury. “Damn it, I’m jealous.”

They’re well-rehearsed but loose enough so as not to streamline the original pastoral quality of their arrangements. The harsh cacophony of Stills’ and Young’s strident lead guttering still injects a bristling tension to the music.

Their onstage personalities are almost intact from 1970. Unless the song demands his presence stage center, Young spends most of his time cruising the amps. His few comments are simplistic (“This is a song for my car,” “This is a song for my dog,” etc.) and their Henry Aldridge ambiance sends waves of uneasy chuckles through the audience unsure if Neil is looking for their laughter or not. He takes particular pride, however, in delivering the “You’re all just pissing in the wind” line from “Ambulance Blues”; it is his only smile of the show.

Crosby, who looks more like Bozo the Clown every day in his purple flares and sneakers, remains the Hubert Humphrey of rock introductions. He seems self-conscious only in delivering the message: “You know, people think we’re doing this for the money, but we’re not. It’s the music man, the music.” Graham Nash is the unobtrusive mortar that binds the other three volatile personalities into a functioning unit, and the high voice that forever winds above the others.

Only Stills appears to have undergone a major transformation. He is quieter now, more disciplined and less self-indulgent in his solo set (his howling piano-pounding “For What It’s Worth” has thankfully been retired). Still, he is fiercely intense and determined to communicate, but not at the expense of those with whom he is sharing the stage. The hostility between Stills and Young that at one time often stopped just short of onstage fisticuffs no longer hangs threateningly in the air. The same lessening of tensions since the last tour has infused the backstage atmosphere with a good deal of genuine warmth, back-slapping, hugging and verbal repartee.

At a quick post-show huddle in the dressing room, everyone is justifiably ecstatic over the performance, but expresses doubts about the potential effectiveness of a four-and-a-half hour show. It is agreed that tomorrow night in Vancouver the set will be trimmed to an airtight three hours.

They don’t meet that deadline. The concern in Vancouver shifts suddenly to David Crosby’s voice. Launching into the second verse of their fourth number, “Almost Cut My Hair,” Crosby’s vocals first turn reedy, then raspy, then hoarse. During the 15-minute break separating the electric segment from the acoustic set, David curses himself dejectedly. “We’re basically a rock and roll band that sings harmonies over soft and electric numbers. I blew my voice out. And when I blow my voice, I blow the harmonies, which blows it for the entire band. I feel like shit.”

Almost on the verge of tears, David trudges back out onstage for “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes.” With Joni Mitchell rooting from stage left, Crosby, and company just barely pull it off, and for the rest of the evening the former Byrd is de-emphasized. Neil does a longer solo set, the “Carry On” jam is extended and the joyous Canadian throng finds nothing amiss. Still, Crosby is too depressed to join the small gathering back at the hotel suite of tour co-ordinator Barry Imhoff.

Ever the showman, Joni finds herself in the center of a picture-window panorama looking out over the Pacific. It is no accident. Eyes shut tightly and voice soaring over the gentle hum of the air-conditioner, she plays her newest songs on Stills’ acoustic guitar, finishes a haunting composition . . .

Just like the walls of Jericho

I fall down, down, down . . .

and lays the instrument across her lap. After a few awkward moments of silence, Stills swoons, “I wish I could think of all those words.” Everyone breaks up. “But then again, I wish I could play with Herbie Hancock too.”

“What room is he in?” Nash deadpans.

Stephen picks up the guitar to play “My Favorite Changes” and “Wake Up Little Susie,” the latter with everyone singing along. “I really want to get into the electric guitar on stage,” says Joni wistfully. “Those acoustics, with all their grey tape and wires, are so cumbersome. Neil gave me his Gretsch, I’ve just got to learn to get comfortable with it.”

As the first sunlight glints through the grey, the suite gradually empties to allow a few hours of sleep before the afternoon flight to San Francisco. There are two days off before the weekend shows at the 75,000-seat Oakland Coliseum. For David, Graham and Neil it will be a home-coming.

***

Graham Nash’s Haight-Ashbury home, like Nash himself, is tall, wiry and highly accommodating. There are four small floors and a cozy basement which serves as a darkroom, as well as the studio where all his recent recording work – including Wild Tales – was done. While the travel-weary Nash sleeps late in the top-floor bedroom, David Crosby is boisterously answering a dialless wooden phone in the downstairs living room.

Crosby has always been the CSNY mouthpiece, onstage and off. A gregarious extrovert, his rapid-fire discourse seems as much for his own enjoyment and amusement as those around him. The obvious pleasure he takes in conversation – he is a good listener as well – creates its own momentum.

“My morale,” he says, “is excellent . . . “

“Good thing there’s an ‘e’ instead of an ‘s’ at the end of that ‘moral’,” cracks photographer-next-door-neighbor Joel Bernstein.

“Fuck you,” Crosby chortles. “My morals are questionable, that’s true, but what do you want? I’m basically – even though egotistically I’d like to think I was more complex – a pretty simple dude. There’s only one thing I’m really good at and that’s singing harmony and writing in groups. Being allowed to do it again after a four-year hiatus is just fucking great. Shit, I know it’s what I’m supposed to be doing. If you can make a lot of people feel real good, you did something right. There’s very few things in the universe you can be unequivocally right about. That’s one of ’em.”

“And that” one wonders, “is your main motivation?”

Crosby doesn’t waste a second in answering. “When I started out being onstage, my main motivation was to get laid. When you’re a teenager and you grow a set of horns, you wanna get laid. That’s basically why I got started. To attract the attention of the female of the species. And, hey man, folksingers get laid a lot more than the other kids in high school. Even if you have to do it in the afternoon on the floor of the coffeehouse. I’m never gonna be good-looking enough to be something chicks would go for on a physical level. They have to be crazy enough to like me, to want to fuck me. I’m not Gregory Peck. They gotta get into the music somewhat. So either way, I got a chance. Singing folk songs, I can tell a story. And if they got a mind, I can find it. If there’s somebody home in a woman, that’s great. It’s also rare. A lot of people are pretty vegetabled-out.

“After that, the motivation became largely winning the respect of my peers . . . I wanted to like me. I started to realize I had some value, that I might be good at making music. Then I went and sang coffeehouses all over the country for a long time. Later, it got to be just winning. When The Byrds were formed, we wanted to win. We wanted a hit. It wasn’t the money so much, it was The Game of competing with the legendary people like The Stones, The Beatles. They were legends to us. Dylan? Naw, not so much because we knew him. We knew he breathed, shat, sat down, fell down, ate, got drunk . . . He was real to us. I’d known him for a long time, from the Village, when he was singing at Gerde’s with the funny hat. I had a perspective on him, it was different. But The Beatles and The Stones, man, they were bigger than life. The Beatles show up a couple times around our recording sessions and stuff, but we were totally intimidated by them. The only one that was friendly at all was George and he was only friendly to me. That didn’t make much of a bridge.

“It was achievement, attainment . . . the bread wasn’t really that big. The Byrds never made any fucking money. I never made any money. Never. The biggest year I had with the Bryds was probably fifty grand. We never made money on our records and, come to think of it, we never really were a performance draw either.”

Crosby grins lopsidedly, the emblematic moustache drooping over what looks like his entire jaw. A natural-born catalyst, he has learned over the years not to take it all too seriously. “I am very serious about wanting to someday write a book and call it A Thousand And One Ways For A Musician To Lose His Way And Forget What He Was Doing. Basically it’s this: There’s only one special thing going on here, and that is the music. The actual magic of that moment when you make yourself and the other people feel something good because of those arranged sound vibrations in the air. That’s the only thing going on. The poetry and the words and the emotion of that music. That’s it. Everything else is peripheral. Not necessarily totally bullshit, but it’s peripheral. Money, sex, glory, great reviews, respect . . . it’s all outside. None of it has to do with the one thing: Did you make that magic or didn’t you? That’s my criteria. I’m not saying anybody else should adopt if – they can draw up their own set of rules – but for me, that’s what’s going on.

“And I personally have lost my way every single way that I can think of. I have been distracted from that criteria by everything. Money? For sure. The first taste of it I got, man, I wanted it all. I wanted Porsches, fancy clothes . . . I wanted it all. The best dope, the most expensive chicks, the most outrageous scene. I wanted houses and cars . . . just crap. It’s all crap. Cars are a real shallow trip and houses are only good to the extent that you live in them. The only material objects that are worth a shit are instruments and tools. Sailboats are a special exception.

“The Byrds, as inexperienced kids not really knowing shit, were given a fistful of those side-tracks. And we went for them whole hog. We fell for the oldest, stupidest American piece of programming there is. The competitive ethic. All of a sudden all our time was spent in preening ourselves rather than playing. Just the fact that you can play guitar does not make you smart. It’s real easy, as soon as anybody is willing to listen, to think ‘Well, they’re listening to me, I must be hot stuff. I’ve got to be smart.’ And then you just motormouth your way into a lot of corners. I still have a tendency to do that.”

In late 1967, David Crosby was booted out of The Byrds. Roger McGuinn and Chris Hilman, so the story goes, roared up Crosby’s Santa Barbara driveway in matching Porsches and delivered the news in no uncertain terms. “Oh it was cold man,” David chuckles. “They said I was crazy, that I was impossible to work with . . . “

“Were you?”

“To a degree, yeah I was. I wasn’t proud of myself. I didn’t like myself and I didn’t like what we were doing. I was a thorough prick all the time. I don’t blame them for not liking me. But it was very cold. They told me I was a bad writer, and I was lousy in the band, that they didn’t need me and they’d do better without me. I was very pleased to find out they were wrong.” Laughter. “It made me feel great.”

And what about “Mind Gardens” from The Byrds’ Younger Than Yesterday LP? “I know, I know,” Crosby interrupts. “That song of mine is supposed to be the worst song ever put on record. Actually, I know a lot of people who really love it. It’s out there. It has no time, no meter, no rhymes . . . and it’s sung freestyle over a lot of backwards guitar. It’s entirely too strange for most people. But that’s how I am. I never was pop in the first place. I’ve always been out on the left-hand edge of everything in this scene and I always will be. I don’t want to sell the most possible records. I’m getting myself off and I will continue to do exactly that.

“My own album [If I Could Only Remember My Name] was the same way. It was very personal and had a lot of things on it that I’m sure a lot of people hate. The six-vocal thing that’s just voices? That’s got to be one of the strangest pieces of music anybody’s put on any pop album in the last ten years. I loved it. To me, it’s a high point in my whole musical career. And I don’t really care what anybody thinks. Graham Nash loves it. McGuinn hates it with a passion. And you know what, I’ll make another solo record and it will be even more off-the-wall than the first! And you know what else? I will love every minute of it!”

After being ejected from The Byrds, Crosby wandered to Florida. “I stopped taking drugs for a while, bought my boat and started getting healthy out in the sun. I stayed there a few months and felt real good. I walked into a local coffeehouse and there was this girl singing ‘I had a king in a tenement castle.’ I went What? Then she sang about two more songs and after I peeled myself off the back of the room I realized I had just fallen in love.

“So I got involved with [Joni] Mitchell for about six or eight months. We went back to L.A. and tried to live together. It doesn’t work. She shouldn’t have an old man.” David whinneys. “But uh . . . it helped me a lot. I had something else to put my energies into. I produced her first album and when I wasn’t doing that I was hanging out with Stephen, jamming and writing songs. Stephen, of course, had just come off the bum trip of the Buffalo Springfield break-up. We had something in common.”

Meanwhile, a third singer-songwriter was terminating his stay in another major group. Englishman Graham Nash, after co-authoring and performing hits like “Carrie Ann,” “Pay You Back With Interest” and “Dear Eloise” as part of The Hollies, began to break out of the strict boundaries that usually beset top-forty pop bands. “I was totally screwed over in that group,” Graham later admits over a beef-stew lunch. “The last two years of The Hollies, I was writing more personal and introspective songs rather than those outward, three-part harmony Hollies Hits. And naturally, they wanted no part of anything that wasn’t a Hollies Hit . . . two-minutes-and-thirty-seconds-of-right-before-the-news-dynamite. I was feeling incredibly frustrated. I mean, I considered ‘Lady of the Island’ and ‘Right Between The Eyes’ to be decent songs. But The Hollies wouldn’t do them. They turned down ‘Marrakesh Express’ too.

“But I don’t mean to say that I quit The Hollies and immediately found my niche in life. I’m totally convinced that what I’m doing now is just a phase of what I’m supposed to be doing in the long run. I don’t plan to be singing ‘Our House’ the rest of my life.”

Crosby unravels the tale. “We were at Mitchell’s house in Laurel Canyon on Lookout Mountain Drive. Stephen and I were singing ‘Helplessly Hoping’ and all of a sudden this third voice is joining in perfectly with us. It was Graham, he had come there with Cass Elliot, and he blew us away. It wasn’t more than thirty seconds of singing together before we knew exactly what we’d be doing from then on. Stephen and I, you see, had already done some demos together. We’d cut ‘Long Time Gone,’ ‘Forty-Nine Bye Byes’ and ‘Guinnevere’ together. The two of us knew we were putting together something very heavy. When Graham came along, there was no choice but to put the snatch on him.”

“Crosby and Stephen gave me back my enthusiasm and confidence,” Nash recalls. “It was almost too simple. I didn’t really know David or Stephen. People were saying ‘Are you crazy? Leaving The Hollies? All that money?!”

“There’s always been a natural chemistry between all of us,” Crosby avows. “Stephen is very much the same kind of person I am. Cocky, feisty . . . a real fucker with a lot of ego. I suppose we admired each other. I respect him very highly. He’s a strong cat. He can fuck up monstrously, as we all know, but when he’s presented properly he can destroy you with the sheer force of his personality.

“There’s a reason for CSNY being as good as it is. The main one that comes to mind is the fact of having each other’s material to juxtapose our tunes with. It makes everything much stronger. A Neil Young song sounds better after a David Crosby song than it does after another Neil Young song. Technically it works, emotionally it works, and in terms of balancing each other it’s a hugely more workable thing. Neil, on his own, has a great deal of trouble externalizing and coming out to an audience. He’ll tend to just get rigid and go inside himself. Stephen too. That’s not my way, obviously. The stage is my backyard. I’m completely unintimidated by it. I love it. I can talk to eight million people without even getting a frog in my throat. But then again, I can’t play guitar like Stephen or Neil.”

It was Stephen’s idea to add Neil Young to the group. “At first, Graham and I didn’t want to do it,” says David. “We knew we had something that worked well and we didn’t want to fuck with it. Stephen, though, knew we needed Neil for the stage shows. We couldn’t cut it as just an acoustic act. We went out to Neil’s house one afternoon and he played some songs for us. He played ‘Helpless’ and by the time he finished, we were asking him if we could join his group. He’s a better poet than the rest of us put together. I hadn’t known him well at all before that, now he’s one of my best friends in the world. He’s crazy, of course, but then again we all are.”

The first CSNY effort, Déjà Vu , was released in spring, 1970. According to Crosby, the album was steeped in depression. His lady, Christine Gail Hinton, was killed in a car accident just before the group entered the studio. “Can’t you tell?” he asks, surprised. “The first one was a joy, the second was painful. I was at the worst place I’d been in my whole life. I couldn’t pull my weight. I would walk into the sessions and break down crying. I couldn’t function. I was in love with that girl. It’s funny, my love affair with Mitchell ran concurrent with our relationship at one point, but I soon realized that one really truly loved me and the other was an experience. You go out looking for princesses, man, and you ignore the little person handing around that you’ve known a long time.

“I couldn’t handle the fact that she was dead, that I didn’t have her anymore. I went completely nuts. For a long time, two or three of my friends wouldn’t even let me go to the bathroom alone. Graham followed me clear to England. Wouldn’t let me be myself for any reason. My father is 74, he says in the long run the only thing that counts is whether you got any fucking friends. All the rest is bullshit. He’s had 74 years to look. I’m inclined to agree with him.

“But now, I’m very much in love with a lady who was Christine’s best friend. I feel good. It was just a thing. I went through it. It’s passed. Déjà Vu, however, is a frozen piece of time. It’s a totally different feeling of album. If there’s anything I can supply in a musical relationship, it’s feeling. I’m no virtuoso at anything except harmonies. None of us are virtuosos. But atmosphere and feeling . . . now, they count for much more than the actual technical quality of the music. During Déjà Vu I felt awful. To me, it communicates. There’s good art on Déjà Vu, but you can’t put it on and feel like it’s a sunny afternoon the way you can with Crosby, Stills and Nash.”

Perhaps prophetically, Déjà Vu was followed by a tenuous on-again/off-again relationship that eventually resulted in Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young scattering in four separate musical directions. A double live album, pointedly titled Four Way Street, hit the racks. “I thought that record was atrocious,” said Stills. “We all did.” And on that note, each one initiated a solo career.

Proving a consistent moneymaker during the separation period, Stephen Stills released two solo efforts and then formed Manassas for more touring and two indifferently received additional albums.

“That initial tour,” says Stills, “ate it. I wasn’t ready. I was playing flat and singing sharp. These days, with rock and roll being such a big business, you’ve got to be good. I’ve always dug my albums, but onstage I couldn’t cut it at first. Not until Manassas did that end of it come together.”

Neil Young hit the number with After the Gold Rush, his third solo LP. Three more commercially successful albums, Harvest, Time Fades Away and On The Beach, followed. Neil kept a low profile, but when he did perform live – as in his last cross-country tour a year ago – halls and arenas sold out strictly by word of mouth. The after-thought member of CSNY had became the biggest solo star. Young even made a film, Journey Through The Past. Now nearly two years old, it is still unreleased – which is a good thing, if the early reviews are to be believed. “We’re still doing some editing on it,” Neil reported. “It’s getting tighter. Chopped about nine minutes the other day. You can barely tell the difference except that it’s better now.”

Young’s massive following cherishes his sequestered enigmatic image, as does Neil himself. At close range, perhaps deceptively, Young appears little more than a content, quiet and uncomplicated 28-year-old man. And yet Graham Nash, who considers himself one of Neil’s closest friends, finds himself on the outside looking in. “Neil is Neil,” Nash shrugs. “I love him.”

Nash has created few commercial tidal waves with his solo works. Songs For Beginners and Wild Tales, preferring to stay with Crosby. Together they did a number of sessions, toured and quietly released a duet album. “I was happy with my solo career,” Nash explains. “You’ve got to understand, though, that individually none of us makes CSNY music. I was content on my own and with David, but there is a part of me that is a part of them. When we’re not playing together, there’s a musical hole in my life. That probably explains the monster rush I got from the Seattle show. When we started ‘Love The One You’re With’ you could have knocked me over with a feather.”

Like bashful school boys returning to class after playing hookey too long, the long-separated superstars first made plans and set aside time for a CSNY reunion album to be rehearsed and recorded in Hawaii, the summer of ’73. After several weeks, the band fell apart once again. No one is willing to say much about what happened. “It’s a four-way marriage,” says Crosby, “and it doesn’t work unless everybody wants to play. We weren’t all into it. It doesn’t matter who was and who wasn’t.” Last year, it seems, it was a little more lunatic than this.

***

Inevitably, the subject of Joni Mitchell comes up. At one time or another, she has been linked romantically with each member of CSNY.

Crosby is adamant. “For my tastes, she’s the best singer-songwriter on the planet. Mitchell just cuts everybody . . . Dylan, you name it . . . to ribbons. She’s the best.”

Nash: “There’s a totality about Dylan’s music that Joni hasn’t quite captured in hers yet. In 1964, Bob Dylan was so unbelievable. It kills me to think about it. Joni’s doing the same thing now, but it’s in a personal rather than social sense. She sees things with such utter clarity . . . “

Crosby: “Dylan could write ‘Chimes of Freedom’ and blow your mind with his insight into the social structure, but Mitchell can write now about people, or your own heart, or your most personal feelings – and she’ll drag them right out just to dangle them in front of you. She makes you look at them.”

Nash: “The amazing thing is, she keeps hitting new peaks. And she knows she’s great.”

Crosby: “Take it from the guys who know. She’s about as modest as Mussolini. She knows.”

Nash: “She does feel uncomfortable about knowing she’s incredible . . . but not for long.” The two collapse in hysterics. “When Joni was a young kid, she decided she’d learn to be a guitarist. So she went out and bought a Pete Seeger guitar instruction record. She went through the chords A, B, C, D, E . . . but when it came to F, it hurt her hand so badly to play it that she threw the fucking record away and tuned the guitar down so she could comfortably play an F chord. That’s how she got started with her amazing tunings. To this day, out of all her songs, only three are played on regular tuning.”

Crosby: “As soon as she junked that record, everyone else might as well have packed it in. They were lost in the dirt.”

The discussion drifts to last year’s ill-fated Byrds reunion album. Crosby winces. “I wasn’t satisfied with it. None of us were. We were all way too careful with each other and the material wasn’t good enough to pull it off. There was nothing real offensive on that record, it was just bland. Painfully bland. No one wanted to step on each other’s toes.”

“What’s to keep that from happening to CSNY?”

“Everything. There’s no chance of this thing turning sour. Everybody confronts everyone else, face-to-face and nose-to-nose, about everything. We’re totally out front with each other. It’s the only way we can function. We have arguments all the time. We have to or else we’ll get trampled. Stephen doesn’t mean to, but he could run right over us if we didn’t balance him. He’s that strong of a person. It’s the same thing with Neil. Graham is too much of a gentleman, but that doesn’t mean he couldn’t completely upstage us all. You wouldn’t even know the rest of us were there. There’s no pussy-footing around going on.”

If everything follows according to the schedule, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young will begin work this month on their first studio album since Déjà Vu. Tentatively titled Human Highway, the album will be preceded by a greatest hits package to be called So Far. Crosby is particularly fascinated by the fact that Neil young withdrew “Human Highway,” at one time the title track of the LP he wound up calling On The Beach, from his own record so that it could grace the CSNY reunion album.

“That was a very strange thing for him to do,” he says, shaking his head. “Neil is a very self-orientated man. He seldom acts against his own self-interest. And yet he did take that song, and a few others [“Tonight’s The Night” and “New Mama”], and gave them to the group. It was a very, very heavy thing for him to do. It blew my mind. He’s got a lot of songs, but those are gems. I thought that was an enormous sign of everything we were looking for in each other. Affection, respect . . . partnership. That’s what it’s all about. That’s what we’re all about. I honestly believe we’re not gonna lose our way this time around.”

Graham Nash nods in silent agreement. “Wish us luck.”

Courtesy of Crawdaddy – Cameron Crowe – October, 1974