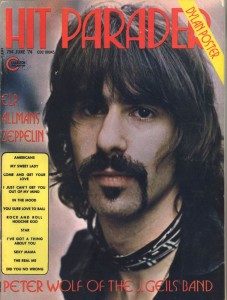

The Allman Brothers Band – Hit Parader

The Allman Brothers Band Together

“This is no advertisement for communes for God’s sake, but there’s a lot of love between us. We are brothers and sisters in this organization.”

In musical terms, the word “band” has become all but obsolete over the years. People have come to disregard the concept of a collective force in favor of viewing a group as the effort of a single member. Fans crave the star image. Magazines demand a single personality. It’s all so much more convenient to have an individual focal point. And granted that much of the time such an attitude is well justified. Many times a band is almost exclusively the work of one musician or composer.

Yet if there ever was a reason not to completely delete the idea of an actual group of musicians, it is The Allman Brothers Band. Until recently, The Brothers were a faceless entity. Their audience was content with a collective identity of six persevering young Southern musicians who had managed to maintain a high level of excellence in the light of two tragic setbacks, the deaths of slide and lead guitarist Duane Allman and bassist Berry Oakley. In a rare instance, The Allman Brothers Band was elevated to their current position at the forefront of rock with the absence of a recognized “leader” or “main” figure.

“You never hear the word ‘star’ around here,” emphasizes organist-vocalist Gregg Allman through a mouthful of pizza, “you just don’t hear it. I mean, ‘rock ‘n roll star’ … what an absurd phrase. It’s like ‘British blues’…”

“I don’t really know what’s going through people’s heads probably anymore than you do,” says lead-guitarist Richard “Dicky” Betts, “but it’s too bad that people tend to take a solid group, single one person out of it and destroy the balance.”

Gregg Allman and Richard Betts, as well as the other four band members, cherish their position in The Allman Brothers Band. They extoll upon the strong bonds holding the band together, stress that each member is equally responsible for The Allmans sound and cannot conceive the group’s non-existence. Still, with the outlets that have opened with The Allman Brothers’ increased popularity, Allman and Betts are the first to pick up on solo LP options. Gregg’s Laid Back has been out several months and Betts’ Richard Forrest Betts is due later this year.

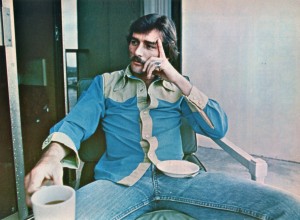

Of the two, Allman is by far the more extroverted. Although there was a time several years ago when Gregg was – as friend Jackson Browne says – “shy … withdrawn. Really withdrawn,” he now is quick-witted and verging on boisterous. Richard Betts is the archetypal quite country boy, less quick to speak out. Manager Phil Walden characterizes him as “a doer, not a talker”. No other description could be more appropriate.

I spoke with Gregg and Dicky in the Allman’s San Francisco hotel-room suite during a stop on their recent West Coast tour.

The Allman Brothers Band seems to stress the close relationship amongst its members, as in the title ‘Brothers And Sisters’. What do you attribute this quality to?

Betts: “Well, most of us in the band are from the rural areas in the South, where a child is raised in a close family relationship. The family is very tight. Three meals a day, carry your lunch to school in a sack … you know, the typical Southern country atmosphere. We’ve since left our blood families and formed our own with this band. We’re trying to hang on to that old thing, I guess. It comes out in the music too. When you get right down to it, music is just a reflection of a musician’s lifestyle.”

Allman: “First of all, we were all friends … if you’ve ever read about wolves, you know they travel in packs. One wolf would die, man. One wolf can’t tackle a moose. He needs the pack to survive. So there you go. Together, we knew that we had something and that no matter how far the bullshit went, we would survive if we hung together. In the early days of the Allman Brothers Band we went out and collected bottles and shit to keep going.

“The way the title Brothers And Sisters came about was that even though we have had two great losses, we were still a family. The title was originally Lightnin’ Rod. But you know, we didn’t band together because we thought if we musicians stuck it out we’d all be driving Rolls Royces. This is no advertisement for communes for God’s sake, but there’s a lot of love between us. We are brothers and sisters in this organization.

You all (the band, their roadies and business managers) have a mushroom, the band’s brotherhood insignia, tattooed on your shins.

Allman: “Yeah, it’s funny. We we got busted in Jackson, Alabama, they were taking pictures of us and putting our hands down in the ink. They had to write down the different marks on our bodies and asked ‘what the hell you all got those damn tattoos on there for?’ Nobody could really come up with an answer except for The Red Dog (percussion roadie), who said, ‘Well man, it’s the brotherhood symbol.’ All they could say was, ‘You mean there’s more of you people.’”

Betts: “Everybody’s so occupation conscious nowadays. A house is just a place to hang your clothes, brush your teeth, and get some sleep. Then you’re back out in the world. There’s still a lot of that old Southern family life around, though. The young boys growing up and learning their daddy’s trade. That’s in a lot of us real strong, that atmosphere. Like Jaimoe (Jai Johanny Johanson, one of the group’s two drummers). You know about Southern black families. They’re so close it’s almost tribal. Our backgrounds have a lot to do with our association with each other. It had a lot to do with our persistence. ‘Course when you’re made so much over and people have turned into a spectacle, it’s hard to keep together. It’s hard to maintain.”

Do you feel you’ve adequately matured to accept success and recognition as part of a new lifestyle?

Betts: (After long pause) “Naw, I fall to pieces every now and then.” (laughter).

Obviously, you think it’s that Southern upbringing that’s responsible for keeping The Allman Brothers Band together despite Duane and Berry’s deaths.

Betts: “Well, the kind of people that are in the South settled this country, so I guess we’re persevering people by heritage.”

Allman: :The time after Duane’s death was the hardest time I figure I’ll ever have. That’s when all the talk of the brotherhood becomes reality. I was in pretty much of a stupor after my brother was killed, but as far as this ‘three year depression’ trash that some magazines printed, I’ve been doing alright for a fucking ‘depression’. Sure, it slowed me down . . . it slowed everybody down. It did a trip on everybody’s head, but nobody laid around and whined ‘Oh God, we can’t make it now.’ We all pitched in. Dicky learned to slide up on the airplane and we built ourselves back up.

“Berry’s death was almost unbearable. What makes it so incredible is that Lamar Williams was the perfect replacement for Berry. It’s amazing we found him.”

Why did ‘Brothers And Sisters’ take so long?

Allman: “Well, that’s obvious. We lost Berry right in the middle of the sessions. It took a month to find Lamar and three months to break him in.”

Betts: “The joke around Macon was that there was gonna be a presentation given to the Allman Brothers Band for being ‘The Band Most Likely To Kill Time In The Studio’. We’d spend a fucking month on one rhythm track and then come in late on Thursday nights so that the band could all watch Kung Fu. The next album is gonna be a live one again. At this point, that’s a very good idea. We’re getting to be some well-seasoned musicians, better every day. And with Chuck and Lamar, it’s a new band. We deserve an accurate document of our stage show right now. I can’t explain enough how much The Allman Brothers Band has matured into being so much more knowledgable of both the stage and the studio. That’s why Brothers And Sisters seems like’s better than anything we’ve ever done. It is.

“I remember ten years ago when I was playing in a bar in Indiana. Our group had a blues song that lasted thirty minutes. We just jammed and well, nobody liked it except the band. What we’re doing now is what I wanted to do ten years ago, it’s just that people are catching onto it now. To be honest with you, I always thought our band played too well to really get through to a mass audience. It surprised me.”

Allman: “The basis of this band has always been to enjoy playing. That’s really the only reason we’re together today. If we’d have started out with the thought of making money, we would have never done it. Our first two or three tours bombed. And I mean bad. We were playing stuff like ‘Whipping Post’ and all the people could do was go ‘Wha?’ If we hadn’t been enjoying it so much, loving what we were doing above all else, I don’t know where we’d be. Certainly not with a number album or at Watkins Glen.”

What were your impressions of Watkins Glen?

Allman: Watkins Glen was great. But it just had the vibes of a very large outdoor gig. There was no real spirit about the whole thing, it was just a concert with a big crowd. I was on a good note that day until someone bonked me on the head with a chunk of ice during our set.”

Gregg, you’re beginning to play more and more guitar on stage. How did you decide to get out from behind the organ for a few tunes?

Allman: “Well, you know that I’ve always played guitar. It’s been about thirteen years now. I used to play rhythm guitar behind Duane in all our early bands, including The Allman Joys. I just felt like getting back into it again. That’s gonna extend itself too. Now that we have Chuck Leavell on keyboards, I’ll be standing up and playing for four, five, or six of the numbers. ‘Wasted Words’ I wrote on guitar and that part had to be in there. Like in ‘Don’t Keep Me Wondering’ (Gregg hums lead guitar part). That had to be played by Dicky while Duane was playing the slide part. It’s very seldom that anybody in the band writes a song and says, ‘Look, this part has to be played like this.’ Usually it’s pretty much up to everybody on the arrangement.

‘Ramblin’ Man’ was so popular, Dicky, does that give you some kind of motivation to start writing and singing more in the Allman Brothers Band?

Betts: “It makes me feel so good that people have put so much value on something l have to offer. Like ‘Ramblin’ Man’. I’m real glad that people from all over the country have been able to identify with the song. I think it’s a damn good expression of the kind of people our band comes from. People in the South can feel my heart beat in that song. Down there, that song is really close to everybody. Everybody knows those places. Everybody knows about 41 running down through Florida . . . but then again, ‘Ramblin’ Man’ was very popular out on the West Coast too. It makes me feel a lot more confident about my playing than ever before. Makes me want to get out there and write and sing all the more. It just tickles the hell out of me.”

How about your solo album?

Betts: “It’s still kind of in the thought process right now. I’ve done some demos, mostly laying stuff down and listening to it to try and figure out what it would sound like as a finished product. I think it might have a mixture of country music and blues. Then I’m going to do some instrumental stuff with Stephane Grapelli. He and Gango Reinhardt used to play a lot like Duane and I used to. You know, real fast, pretty harmonies and melodies. We might re-cut ‘Revival’ as an instrumental with Grapelli on slide and myself on guitar.”

Do you look forward to your next album, Gregg?

Allman: “Yes and no. I enjoyed Laid Back. It was quite a lot of work, but I was satisfied. The next one should be a lot easier, now that I know the pitfalls you can fall into with a project like that. But right now, I’ll tell you that I’m so sick of looking at the inside of a studio I could puke.

“The other problem is that people start talking about you leaving the band and shit once you get into solo albums. This shit that was printed recently about me leaving the band – about any of us leaving the band – it’s a bunch of God damn… well, it’s not even horse shit. I’d rather have some horse shit than listen to that drivel. We’ll be playing as long as there’s somebody there to listen.”

Courtesy of Hit Parader – Cameron Crowe – June, 1974