Almost Famous – Rolling Stone

A Boy’s Life

In Almost Famous, the director relives his glory days as a teen reporter for Rolling Stone and creates the freshest rock movie in ages.

It’s one thing for Cameron Crowe to make a movie about his teen years as a rookie rock journalist for this magazine, among others; it’s another to find the kid to play him. For weeks now, the buzz has been strong on Almost Famous, the film memoir written and directed by Crowe, forty-three, to capture the giddy expectancy and sobering betrayal of getting close to the flame of the Seventies rock scene. Despite the $60 million bankroll it took to make Almost Famous, the film has a low-budget heart. Crowe wanted to keep things personal. Maybe that’s why he had such a hard time finding the actor to take the ride through his formative years as William Miller, Crowe’s alter ego. During the 1999 casting process, audition tapes piled up. Nothing. Then Crowe saw Patrick Fugit. The sixteen-year-old unknown from Salt Lake City had almost no acting experience. Great. Fresh clay. There was only one problem: about twenty-five years worth of rock & roll. “Before this, I had one Chumbawamba CD – that was it,” Fugit says with a sly chuckle. “I actually thought Led Zeppelin was the name of one guy. Same thing with Jethro Tull.” Crowe doused the young actor with music and forever changed him. “Cameron gave me this huge collection of CDs,” Fugit says, “and told me to have them coming out of my pores by the time we started filming. Now I’m almost as obsessed as he is.”

Not likely. The CDs were just a start. Crowe calls Almost Famous his “love letter” to the music and the family he found in rock & roll before he went on to adapt his 1982 novel, Fast Times at Ridgemont High, for the screen – and to write and direct Say Anything . . . (1989), Singles (1992) and the Oscar-nominated Jerry Maguire (1996). All these films draw on Crowe’s life and his love of music, but Almost Famous digs deep into the time when rock & roll first lays claim to your soul: a time when hormones romp, love hurts the most, and rock stars loom taller than gods.

Try acting that. It was Fugit’s challenge to bring out the many sides of William: the son whose mother, played by Fargo Oscar winner Frances McDormand, bans rock from the house (“Honey, it’s all about drugs and promiscuous sex”); the fifteen-year-old fledgling journalist who lies about his age to snag an assignment from Rolling Stone; the shy, music-loving kid who cuts school to go on the road with Stillwater, a composite of bad-boy bands like Led Zeppelin, the Allman Brothers Band, the Eagles and Lynyrd Skynyrd. Along the way, William strikes a nerve with Stillwater guitarist Russell Hammond (Billy Crudup), the self-proclaimed “golden god” who blurs the line William tries to draw between fandom and his vocation. William also lives out many a teen boy’s fantasy: A trio of groupies deflowers him. Then he falls in love, hard, with Penny Lane (Kate Hudson), the groupie queen who is hopelessly devoted to Russell even when he cashes her in for fifty bucks and a case of beer in a poker game.

How does an inexperienced actor prepare for a role like that? “I was so green and exposed to everything so quickly,” says Fugit, now a year older, with his voice two octaves lower and his frame three inches taller than his screen persona. “It was like an express lane to the front line.” So Fugit did what any raw rookie would do in that situation: He enrolled in the school of Cameron Crowe.

On January 1st, 1973, fifteen-year-old Cameron Crowe, a precocious student from University High School in San Diego, fulfilled a dream: He interviewed Poco for the magazine you now hold in your hands. Poco were led by Richie Furay – best known as a member of Buffalo Springfield, with Neil Young and Stephen Stills. Crowe, decades away from directing Tom Cruise in a film that grossed north of $160 million, was best known – among his pals, at least – for hustling Rolling Stone into paying him $350 for his first story. After a few more pieces, Rolling Stone editor and publisher Jann Wenner wrote Crowe a letter of encouragement: “Who knows, you may turn out to be the youngest Rolling Stone man ever. . . .”

The words were prophetic. Crowe, who lied about his age to nab his first assignment, remains the youngest correspondent the magazine has had since its 1967 debut. In his years as a rock journalist, Crowe interviewed Led Zeppelin, the Allman Brothers, Yes, the Who, David Bowie, Elton John, Peter Frampton, Lynyrd Skynyrd and most of the players in what is now considered the classic-rock canon – and all before his twenty-second birthday. It’s no accident that Almost Famous is filled with songs by those musicians. For Crowe, it’s the soundtrack of his early life.

Cameron Crowe is a pack rat. He and his wife of fourteen years, Heart’s Nancy Wilson, have a house in the woods of Seattle, and they are moving from their Los Angeles apartment to the L.A. home they have recently bought to share with their seven-month-old twin sons, William and Curtis, and three dogs. For the past fifteen years, they have lived in their narrow, dark and cool three-floor condo when in L.A., but the real tenants here are inanimate: Their records line an entire room, floor to ceiling, and the living room and second-floor office (don’t even ask about the garage) are crammed with Crowe’s endless boxes of transcripts, photos, films, scripts, bootlegged concert tapes and seemingly every piece of paper he has ever written on. Crowe’s hands are the first thing we see in Almost Famous – fittingly, he scrawls the opening credits on a legal pad.

A giant box at his feet is piled with the mix tapes Crowe has made every month since 1978 – an effective snapshot of his day-to-day life. “It’s fun to see what you were listening to in August ’95,” he says. “There were songs that kept coming up that reminded me to do this movie.”

Crowe darts about the house pulling pictures from the wall (one of his wife as a stewardess from a cut version of the final scene of Say Anything . . .) and memorabilia from drawers (a framed John Lennon letter to Francis Ford Coppola, rare Heart artwork), all the while answering – and often redirecting, as only one used to the other side of the microphone could – questions about himself. At one point, he admits his discomfort at “proclaiming the glory of me,” and proceeds to interview his interviewer for half an hour. Despite his credentials as an A-list Hollywood filmmaker, Crowe still exudes the enthusiasm of a teen. He is also dressed like one: baggy green cargo shorts, a long, black T-shirt and some brand of extreme jogging shoe. His brown eyes twinkle with a sensitivity that has undoubtedly earned him the elusive trust of the suspicious. He speaks thoughtfully, taking pains to be clear and clearly relishing the interplay of conversation.

Crowe heads down a hall to the record room. In it is a round, red table. Bob Dylan once sat here with him to discuss the songs collected on the 1985 compilation Biograph, for which Crowe was tapped to write the liner notes – a rare second chance with the poet of a generation. “I had tried to interview him in ’78,” Crowe recalls, “and tanked. He was sitting on a bed in a rehearsal studio when he was doing Street Legal, and he had records spread out in front of him. He had just bought the Sex Pistols album – and I fucking didn’t ask him about it! Anyway, in ’85, the record company tells me he’ll do an interview for the liner notes, and that he’s coming into town and will come to my house.” After a whirlwind cleanup, Crowe and Wilson were ready – sort of. “So the buzzer rings, and he says, ‘It’s Bob.’ I go out to the gate, and he’s iconic, sitting-standing on his motorcycle, with his hair looking like early Bob. And one of the yuppie women who lived here at the time is standing at her mailbox, frozen, just staring at him. He’s completely Highway 61 Revisited – right there!” Wilson was too freaked to come downstairs to meet Dylan, but the interview was stellar. “The whole thing was me pitching him song titles, and it went well because I didn’t get personal,” Crowe says with another of his endearing, frequent grins. “Except for this: I say, ‘What were the Sixties like to you?’ He just says, ‘The Sixties were like a flying saucer. You know, everybody talks about it, but nobody saw it.’ ”

Not so for the Seventies; Crowe absorbed the sights and sounds of that decade with the fervor of a documentarian. Right now, the Dylan table is covered with photos, notes and discarded script pages that, over time – over a long time – became the film that is Almost Famous. “Everything was hard on this movie,” Crowe says, bent over collected print ads from the Seventies. “It was by far the hardest thing I’ve done. I tortured all of my friends, just calling all the time and moaning about it. They all said, in gentle and not-so-gentle ways, that his one was hard because it is about me.” Crowe is a fan of the personal album: the early, often awkward effort in which an artist is unintentionally revealed, the album without pretext. “Almost Famous is my most personal album,” he says. “I did want it to come off like a piece of music.”

His wife agrees. “There was a lot of procrastination on Cameron’s part because of the personal nature of Almost Famous,” Wilson says with a chuckle. “There was a lot of deep, dark doubt about even doing it. I don’t mind being a cheerleader, but I did reach my limit quite a few times. I do my own writing, so I understand, but I was pushed to the point of anger with the insecurity of it. Just when I’d have him all pumped up, the next morning it would start over again. His mother and I were a support group – with no paycheck. But I knew all along it was worth it.”

As in the film, Crowe’s mother, Alice – a college teacher, now retired – did not allow rock & roll to be played in their home. “The thing about my mom is that she thought she was cool,” Crowe says affectionately, taking a seat on his living-room couch. “She wasn’t going to buy this tripe from rock bands trying to pull a fast one on her. She got so pissed off when Simon and Garfunkel sang ‘Mrs. Robinson’ on The Smothers Brothers Show that she wrote a letter to the head of NBC calling it a glib, exploitative disgrace. Rock was smuggling in shirt disguised as candy.”

Crowe’s older sister, Cindy, smuggled in records, hiding them under her bed; she passed them on to Cameron when she left home for college. “Those are all my albums in that scene where the kid is looking through them in the room,” Crowe says proudly. “I shot that scene so many times with the albums in different orders, but Pet Sounds was always first. That album is the sweetest sad thing I’ve ever heard. This movie is sad and sweet, too. I could never aspire to make a movie as profound and deep as Pet Sounds, but I can make a movie about what it’s like to be a fan of Pet Sounds.”

Crowe’s father, James, who died in 1989, doesn’t figure in Almost Famous. “It’s just more powerful and truthful not to have my dad in the film as just a sidekick to my mom,” says Crowe, who promises to write about his father someday to honor his support in an anti-rock house. Alice Crowe was and is a formidable presence who instilled her love of knowledge in Cameron at an early age. She saw an intellectual kindred spirit and encouraged it with literature and foreign films. “His mother had an important impact on him,” Billy Crudup says about the character and Cameron himself. “Despite the fact that he uses it to seek out rock & roll, he has the mind of an academic, which is to break down a mass into particles to understand the whole thing.”

Alice hoped that Cameron would become a lawyer. He thought he would, too, until he saw his first issue of Creem. “There was this head shop downtown in San Diego where they sold Zap Comix and rock magazines like they were porno,” Crowe says. “You had to be eighteen to look at them, but there was a guy who would let me. I thought it was the greatest thing. The guys that wrote for them tweaked the music – but respected it and lived this rock-filled lifestyle.”

Crowe’s career path took a definite turn after his sister brought him to a meeting of the local underground paper, the San Diego Door. “She was going out with guy on the staff and brought me to a meeting, under the condition that I not tell Mom,” he says. “There were these great-looking movement women in tank tops smoking weed.” Crowe asked if he could submit record reviews, and he struck gold: “They were like, ‘No. Music is a corporate tool… Well, we do need the advertising from the record companies.’ Then they tell me about this guy who did reviews and still sends them in. And it’s Lester Bangs. They show me this file, so thick that they hadn’t even been read or printed. First-draft shit, written on the back of bios. What I would give to have that stuff now.”

Crowe sent clips to Bangs, who had worked at ROLLING STONE for a while before joining the staff of Creem magazine, led by another former ROLLING STONE editor, Dave Marsh. Bangs, played in Almost Famous by Philip Seymour Hoffman, became Crowe’s Yoda, guiding him through the rock & roll circus over the years. “I first met Lester when he came to San Diego – and everything happened as in the movie,” Crowe says. “He would always warn me about keeping the rock stars happy. I’d tell him I had written about Rod Stewart, and he’d say something like, ‘Great, Rod Stewart… fat, sassy, rich, sitting in a nice, big hotel room. Am I right?’ “Yeah,’ I’d say. ‘And do you know what your purpose was coming into that room? To keep him in that rich, fucked-up hotel room.'”

Bangs, who died in 1982 of an accidental OD of Darvon and Valium, had a clear-eyed, merciless attitude about the forces – money and fame – that corrupt music, but Crowe needed to capture what people didn’t always see. “Lester had a strain of compassion that he begrudgingly indulged,” Crowe says. “What a hero! A sentimental guy that would puke if you called him sentimental. The one thing he said to me that day in San Diego that’s not in the movie was this: “I can’t stand around talking all day. I have to go drive by the house of the girl that broke my heart.’ It wasn’t a violin moment; he just didn’t want to pass up the chance fro some good romantic slop. Then he said, ‘I’ll see ya… Hey, you hungry?'”

If Almost Famous is Crowe’s love letter to music (Frances McDormand responded, “I love your love letter,” by way of accepting her part as the boy reporter’s mother) and to his biggest influences (he calls his mother and Lester Bangs his “Twin Towers”), it is also a film about families – the one you’re born with and the ones you find. Rock writer Jaan Uhelszki, an old friend, told Crowe that he didn’t make the movie for music, he made it to get his mother and sister talking again. She was right. “My sister and I had a falling out after my dad died, in 1989, and didn’t talk for a long time,” Crowe says. “Just the other day, we had the best talk that we’ve had in a while because of this movie and the things it brought up.” (Near the end of the film, brother, sister and mother achieve a tentative peace over breakfast and, of course, music.)

“After my dad died,” Crowe continues, “the chemistry of my family got fucked up, and in my wildest dreams, I hope the movie helps my mom and sister communicate. They talk through me now, but three and a half weeks ago our family got together.” He looks at a pile of records for a moment, then turns back. “The one fake scene in the movie – the reconciliation at the end – actually happened in its own weird way,” he says. “My mother and sister did get together, and it was amazing.”

Scene from “Almost Famous” – morning on the Stillwater tour bus. Elton John’s “Tiny Dancer” plays on the stereo. A voice or two sing along. Then others… waking up, joining in.

William: I have to go home.

Penny: You are home.

The Allman Brothers were the subject of Crowe’s first major ROLLING STONE story. “So much of it became the movie,” he says. “It was the first time I left home for any length of time, and I was calling my mom from the road telling her I’d be gone just one more day.” (Crowe is still fond of calling friends “brother,” a term of endearment he picked up from the band.) At the time, getting access to the Allmans – especially ROLLING STONE – was the holy grail. Duane Allman and Berry Oakley were dead, and the band had declared a press ban. “They also felt they have been wronged by ROLLING STONE,” Crowe recalls. “There was a story done by Grover Lewis, who had toured with them and gotten in deep. He wrote a riveting story, but had them all getting high, and Duane came off like a cracker.” Crowe, on the advice of the band’s publicist, did an interview with guitarist Dickey Betts without addressing any of their recent hardship: “I interviewed him on the plight of the Indians. He had just married an Indian girl, and that’s all he wanted to talk about. And at the time he was going by ‘Richard,’ which was the only way I referred to him.” Betts was comfortable and soon started discussing the difficulty of carrying on without Duane. “I was like, ‘Holy Shit!'” Crowe recalls, fidgeting a bit at the memory. “I immediately called Ben Fong-Torres.”

Fong-Torres, a senior editor at ROLLING STONE from 1969 to 1981, and now editorial director at Myplay.com, had been impressed by the young Crowe. “I knew he was under twenty-one,” Fong-Torres recalls. “I thought he was eighteen or so. I don’t remember every really tracking him, but Cameron tells me his sister told me his real age. We have slightly conflicting memories, but I’ll defer to his, because he has one. At age forty-three, he still looks young. Anyway, after we knew how old he was, we were proud of it. We added a footnote to his next story about it. We were feeling so old at twenty-five, you see.

“It’s a wonderful film, one of the truer representations of the passion for music,” says Fong-Torres of Almost Famous. “Cameron has shown an amazing skill for being totally human with his characters, and now he’s done it with this own. But it’s kind of ironic that he although he was faithful – as much as he could be within Hollywood confines – to his situation with ROLLING STONE, he chose to hide himself behind a different name and image while using the rest of us in a true-to-life capacity.” The two worked together during the next five years. “I edited every story of his for his first year,” Fong-Torres recalls. “I know I had to be presented in one dimension to serve a function in the screenplay, but he didn’t include the fact that I went on the road as much as he did. It seemed that all I did was get on the phone and yell at him. Also, in the situation with the band [onscreen, Fong-Torres and other ROLLING STONE editors threaten to kill William’s Stillwater story when guitarist Russell tells a fact checker that he’s been misrepresented], I, and ROLLING STONE as well, would not have abandoned the writer in favor of the band’s word. We would have confronted the artist with the tapes we see William recording all through the movie and gotten them to be honest.”

Of course, there are some things editors don’t find out until, in this case, twenty-seven years later. Here’s Crowe on what really happened with the Allman Brothers: “Gregg was this towering, suspicious, incredibly vivid guy,” Crowe recalls. “I finally got him to talk to me because I knew that he thought Jackson Browne was a great songwriter, and that Jackson thought Gregg did the best version of his song ‘These Days.’ So one night in his room, I ask Gregg to play it.”

Allman did, and kept playing songs – all of which Crowe has on tape. “All I could think was fandom… professionalism… he’s got me,” Crowe says. “So I decide I’ve got to get the full story, and I ask him about Duane. And he tells me about Duane. So much so, in fact, that it nearly backfired on Crowe’s last night on the tour: “After the show in San Francisco, Gregg called me up to his room and told me to bring all of the tapes. I did, except the one with him singing on it. He answered the door, looking like he was just in another place – ‘fucked up’ doesn’t do it justice. He looked like he had seen a vision.”

Allman sat the young teen down in a chair, asked to see his ID, and did not like what he saw. “Gregg says, ‘Who are you? You’re sixteen! How do we know you’re not a cop? We could be arrested for having you out here with us. How dare you not tell us your age! You see that empty chair? My brother is sitting there right now, laughing at you!’ I had never been more scared in my entire life.” Allman kept the box of interview tapes, and a broken Crowe handed Fong-Torres a draft written without them: “The piece was mostly a history of the band – Ben kept saying, ‘Didn’t more happen?’ I couldn’t tell him – it would have ruined me.” Among journalistic sins, turning over interview tapes to an interviewee ranks high. “The whole reason the band was giving me the story is that I was the kid,” says Crowe. “That moral dilemma never left me.”

A few days later – luckily in time for revisions – Crowe’s longtime road partner, photographer Neal Preston, retrieved the tapes. “Neal called to say the tapes were on their way,” Crowe recalls, “and that Gregg didn’t even remember why he had them. Last year, Neal photographed Gregg, and Gregg asked him whatever happened to ‘that guy who was with you when we first met.’ Then he says, ‘We really put that kid through the wringer.’ It really got me, because I had just finished the movie about the kid who gets put through the wringer.”

By mid-’73, Crowe was the hardest-working teenager in rock. A look into his planner from that year (he has it, of course), which is plastered with stickers from promo albums – Grand Funk and ZZ Top – reveals full days like these:

Thursday, March 29th: Neil Young at Sports Arena; Yes arrive in Los Angeles, staying at Beverly Wilshire; Bee Gees in Santa Monica; call Warner Bros., re: Alice Cooper; call Asylum, re: Jackson Browne; Shakespeare test – “Merchant of Venice.”

Friday, June 1st: History final 8 A.M.; Biology final 12-2; Gregg Allman solo album released; Led Zeppelin in L.A.

Friday, July 13th [Crowe’s birthday]: with Led Zeppelin in Detroit; Allman Brothers story due at “Circular”; leave for San Diego.

Crowe never went to college, but he did think about it. Or, rather, his mom did. “My mom worked at City College in San Diego, and during this time she enrolled me in biology, history and journalism, to get me interested in the college experience,” he says wryly. “My journalism teacher came to me one day and told me I had to show up to class more often. And then he said, ‘By the way, can you get me published in ROLLING STONE?’ I went home and told my mom that if the journalism teacher is hitting me up to get published in ROLLING STONE, that’s what I should be doing – ROLLING STONE is my college. So that guy got me out of school. Thanks to him.”

It was Crowe’s enthusiasm for his subjects and his natural ability to be sympathetic that got him on the road, and his rock-solid upbringing that kept him from losing control out there. “I remember that I really trusted Cameron,” Stevie Nicks recalls. “I really loved the way he wrote, and I trusted that he would write down the right thing and not take it anywhere else. We didn’t bring just anyone around like that. As a performer, you want to remain mysterious – there is a lot of crap that is not for the audience to know. Cameron would be around for it, but he would never tell anyone. He was honorable. And that’s why people let him hang out.”

Some things never change, a fact not lost now on Fleetwood Mac drummer Mick Fleetwood. “Cameron is one of these chaps who looks like he’s on a Dick Clark regime,” says Fleetwood, calling from his mother’s country home in Salisbury, England. “He has always just looked like a puppy dog. He still dressed with his little shirts hanging out, doesn’t he?” Fleetwood was aware that writer and band enjoyed a mutual appreciation that allowed Crowe to get the stories others didn’t. “He was a cool guy – not jaded at all, just so happy to be doing what he was doing,” says Fleetwood fondly. “We became friends in those days.”

The good word of fellow musicians never hurt, either. “Sometimes bands would suggest me to other bands, which was great.” Crowe says. “It happened with David Bowie: Ron Wood and Glenn Hughes from Deep Purple put in a good word for me. I had a reputation for undying interest. Glenn actually came to my house once when I was living with my parents. We were talking on the phone, and he just drove down from L.A. I remember the feeling of trying to hide stuff in my room because it featured them, and also trying to savor the moment as it happened. We went and hung out in the clubhouse of our condo complex, where you’d play pingpong.”

There were also moments when fandom had its downside. Crowe had more than a few reminders during his early days that, emotionally, he was still a kid. “I really hit the wall on the road with Led Zeppelin,” he says quietly. “I felt like I wasn’t going to get the story. Jimmy Page still hadn’t agreed to do an interview, because he didn’t want to do it for ROLLING STONE” – the band had been, in Crowe’s words, “continually kicked, shoved, pummeled and kneed in the groin” by STONE music critics. Finally, Page consented and Crowe flew off to meet him at the Plaza in New York. “My mom and dad were really pissed, and my eyes were so read from stress and no sleep that no amount of Visine would change it. I started wearing sunglasses around.”

Historical reconstruction, when done well, is like a game of charades with vivid hints. Some of the events in Almost Famous beg deciphering. Let’s clarify a few things.

What about that scene where Russell, on a bad acid trip, climbs up on the roof of a fan’s house and yells, “I am a golden god”?

Robert Plant – he was joking around and said it while looking over the Sunset Strip. He and Jimmy Page saw the movie, and when Billy Crudup’s character is complaining about the story and says, “I didn’t say, ‘I am a golden god,'” Plant shouted, “Well, I did!”

In the movie, you and Stillwater are on a plane that nearly crashes – an incident that inspires moments of confession. Any real-life basis for that incident?

I was on a really bad plane flight on the Who tour in 1973. They let me fly with the T-shirt-merchandising: one stoned guy with a box of T-shirts. He was so eager to get to the next city to see this redhead that he flew us into a storm and went as fast as he could. I swore I wouldn’t go on any more private planes. Then I got together with Nancy, and Heart did a tour with a private plane, where I took the second-worst plane flight of my life. We were in a storm so terrible that you really were looking at people for the last time. We ended up landing in Tupelo, which is why’s Tupelo in the movie. The joke was that we were going to die in Elvis’ hometown, so it could never be famous for where we crashed.

Did any deep, dark secrets come out?

That scene is an extension of it, but it started to happen. Everyone’s darkest, most hysterical side came out. Afterward, I couldn’t believe that the embarrassment could be so large that living was almost second prize. I remember walking down a hallway looking at everyone, thinking, “We’ve been in the crucible together, and I’ll never look at you the same way again.”

Who is Russell Hammond, really?

I saw Glenn Frey at a dinner party recently, and I realized that so much of Russell is Glenn. He was the coolest guy I had ever met in 1972. I was backstage at a concert interviewing everybody – the Eagles, King Crimson, Ballin’ Jack, Chaka Khan. In the Eagles’ dressing room, everyone’s talking about Glenn – the one guy who isn’t there. He’s out looking for babes. Everyone’s like, “The thing about Glenn,” “Oh, one time Glenn and I…” And then, like a one-act play, Glenn appears. He walks in a little buzzed, he’s got al long-neck Bud, and he’s like, “How ya doing’?” Just classic. That whole thing of “Tonight, friends – tomorrow, the interview” was him. And there’s one line he really did say to me: “Look, just make us look cool.” He was also the first guy who told me about crafting a buzz long before I could ever enact it.

The recipe, please.

OK. He’s like, “If you want to craft a buzz correctly, you walk into a party, you drink two beers quickly. Then you drink a beer every hour and fifteen minutes after that. You’ll always have a buzz and you’ll never get too embarrassing.” I was like, “Uh… yeah, I know that.” Meanwhile, I’m furiously writing it down.

Did you lose your virginity to a group of groupies?

I… that happened to me. That scene was truthful.

You teenage stud!

I was not a stud. The girl I wanted did not stay. That girl was sold for beer, just like in the movie. I never knew what happened to her. I tried to track her down before we started the movie, but she has a new last name now. She did e-mail our Web site recently.

The colored lights are on Stillwater in Almost Famous, but the light that shimmers brightest is the character Penny Lane, the self-proclaimed Band Aid who, to Crowe, represents the soul of music. “I didn’t want to do a tragic portrait of groupies with needles in their arms,” he says. “I didn’t remember those people as vividly as the ones who would go on and on about Exile on Main Street. You’d wonder if they could get off on sex as much as they did on rock.” The character is loosely based on Pennie Lane, an Oregon native who had a school for her Flying Garter Girls and specific rules to live by. “They were these soulful girls who told you and themselves that they didn’t get involved emotionally,” Crowe says. “Only later did I realize that they all broke the rules, got emotionally roughed up and came back for more – like any great idealist.”

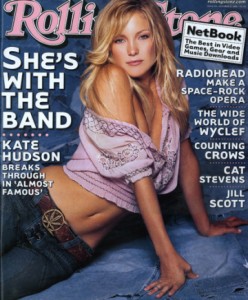

Penny is a breakthrough for Kate Hudson, 21, who was originally lined up to play William’s sister. Hers is a tender portrait of a sensitive girl who wears many masks. In person, Hudson shows an equally deep river of feeling just below the surface. “There’s a sadness and vulnerability to Penny Lane’s character,” she says. “I spoke to the ex-wives of some rock stars – whom I won’t name – and there is a sadness and mystery to all of the crazy things they did. It was fun, but it could also be painful for a woman in that world at that time.”

As the film wrapped, Hudson met the real Pennie Lane, now back in Oregon. “I am starting the Raisin Ranch – a home for retired rock stars and wayward groupies,” says Lane. “We can play music really loud – and we’ll have to, because everybody will be deaf, since nobody wore earplugs.” Hudson admires her spirit: “She really had that sparkle in her eye and that grand posture – this elegance without arrogance. To see her with Cameron, his body language totally changed. I don’t know if he’ll admit it, but he totally became William. And Pennie just came up to him and said, ‘I am so proud of you.'”

Bangs and Fong-Torres had honed Crowe’s skills, and his zeal for the music kept him working hard, but by the end of the Seventies he was ready for a change. “I started to burn out on journalism,” he says. “I was no longer the Guy – I was taking on too much, and taking too long with stories. I didn’t know how much further I could go. I wanted to interview Marvin Gaye, but he wasn’t doing interviews, and I really wanted to do a Rolling Stones story for ROLLING STONE, but that list was very long.”

Crowe left journalism and focused his absorbent perception elsewhere. He went undercover as a student to write his first novel, Fast Times at Ridgemont High. Before he had even finished, he was tapped to adapt the screenplay for the film, directed by Amy Heckerling. After that, Crowe decided to direct his own, customarily taking three or four years between films. So it’s quite a surprise that he will soon begin shooting Vanilla Sky, a love story with a psychological theme that re-teams him with Jerry Maguire star Tom Cruise, less than a year after wrapping Almost Famous. “I’m running out of years to play with,” says Crowe of his accelerated schedule. “It’s like, ‘Speed it up, brother.'”

Or maybe it’s just that Crowe has finally got his own life off his chest. “Almost Famous was always the movie I’d go back to, to avoid the movie I was doing,” Crowe says, smiling. “I’d say, ‘Why am I doing a movie about a sports agent? I want to do a movie about music!’ Even after Fast Times, when people would say, ‘This is the best story – and you lived it!’ I was thinking, ‘This is not the best story I have. Someday I’ll write it.'”

When Crowe ran out of excuses and finally began the script, it didn’t get any easier. The writer turned to his wife and to his mother. “She and Nancy are really everything,” he says. “My mother is my best editor. She’s positive – but brutal. I’ve never been to therapy, but she was a shrink figure during the making of this. She’d say, ‘It has the possibility of being your best movie if you stick with it.’ Coming from the person who gets her ass hung out on the line a bit in the movie, that was amazing.”

Alice – although long retired, she still informally counsels students – unknowingly crafted one of the film’s most memorable lines. “I would talk to her late at night, and she’d be so inspiring,” Crowe says. “I’d go back to work, then I’d hear the fax machine. All of these inspirational faxes would come through. When this one came in, I put it right into Frances’ mouth.” It’s a quotation: “Be bold, and mighty forces will come to your aid.” Beneath them, also in quotation marks, is a capital M.

McDormand connected immediately with the mother-and-son bond at the center of the film. “It’s an amazing homage,” she says. “He’s made his mother a three-dimensional character with her own story. He really honors her and honors their relationship. It’s to her credit. She said to me at one point, ‘I was a little dissatisfied that he didn’t become a lawyer and chose to go into the arts.’ The arts? I laughed. I wouldn’t call movies the arts.”

Don’t say that to Crowe, or to Seventies rock-god guitarist Peter Frampton, who served as “authenticity adviser” on Almost Famous. “First off, we were sure to have the correct equipment,” Frampton says. “Most rock movies are never authentic – you’ll have someone supposedly in 1958 playing a 1990 guitar, and a 1986 microphone. So we were sure to get the little things correct, like strap locks. Back then, there weren’t strap locks on guitars, so you attached them with a dog clip, like on the end of a leash – you can see it on the cover of Frampton Comes Alive!” (for which, by the way, Crowe did the liner notes).

Along with Crowe and Nancy Wilson, Frampton wrote the original Stillwater tunes, appeared in the card-game scene and, most important, was the headmaster of what came to affectionately be called Rock School. In the film, the members of Stillwater are played by two John Fedevich and Mark Kozelek, and two actors, Crudup (on guitar) and Jason Lee (as singer Jeff Bebe). Some fine-tuning was clearly in order. “Basically, we had band practice… with Peter Frampton,” Crudup says with a laugh. “I would not have imagined that I would be sitting there, learning to play rock songs and being paid. I didn’t think it was in the realm of possibility – otherwise I would have asked for it sooner.”

Fugit also enrolled at the Rock School. Like Crudup, the kid has taken up the guitar full time and jams with friends back home. “I’m not saying I’m cool or anything,” he says. “But I have a few more friends and wasn’t quite as nerdy as William. Almost there, but not quite.”

The Rock School also helped form a little bond between Fugit and Crudup, a stage-trained actor who grew up in Virginia, Texas and New York, attended New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, and made his name in indie films such as Waking the Dead and Jesus’ Son. Crudup, 32, says he is just as suspicious of celebrity as his character is. “Russell is constantly trying to simplify his life and get back to the point where he was just playing music with his buddies,” he says. “He’s struggling with how art and commerce collide. Actors, by virtue of being actors, are celebrities. That’s dangerous – provokes a perverse value system. Lester Bangs predicted the future.”

Fugit, too new to fame to share Crudup’s fears, saw the movie as a baptism. His sensitive portrayal of William captures the sad sweetness of first experiences. Fugit didn’t have to do much soul-searching. “William is in this whole new world, and he’s growing up at the same time,” Fugit says. “The same thing was happening to me.”

Scene from “Almost Famous”:

Penny: Honey, you’re too sweet for rock & roll.

William: Sweet! Where do you get off?… I’m not sweet…. I’m dark and mysterious and pissed off, and I could be very dangerous to all of you… I’m not sweet, and you should know that about me! I am the Enemy.

“I had to defend being a fan a lot back then,” Crowe says about his former career as a journalist. “Fandom had and has a bad connotation in journalism. But you know what? At some point you’ve got to say, ‘I write for The Ring magazine… I love boxing!'”

Crowe has not always felt this way. “I’ve always been told, as a writer and director, that I get taken advantage of because I’m naive. There certainly was a time when I wished I had used more of a rapier sword to write those stories, but I don’t feel that way anymore. A lot of those bands are dead or not around. Press clippings are the only things we have to go by. I loved knowing that a band threw TVs out the window, but I never led with the outrageous when I could lead with something about the music.”

Undoubtedly, some will similarly criticize Almost Famous: The heralded sex and decadence of Seventies rock has its place in the film, but, like William and the groupies, it occupies the side of the stage. “The people I thought I would never see again are coming out of the woodwork,” Crowe says, beaming. “Almost to a person, they tell me the same thing: ‘I hope you didn’t just write about the exploitative stuff – I hope you wrote about what it was really like.’ Of course, now I feel like I don’t have enough exploitative stuff.”

Choosing thematically poignant scenes over reveling in bad behavior only clarifies Crowe’s focus in the film – family. That’s why Almost Famous remains the hardest project he’s ever tackled: “I am doing ‘Welcome back, my friends, to the show that never ends.'”

It was worth it. The film has already brought his family closer, and though his mother and sister declined to be interviewed for this story, they each sent messages via Cameron. “My sister wanted me to tell you that she’s worked very hard to build a normal life for her three daughters, and that she doesn’t want them to deal with the media glare of their mother being quoted in the press,” he says. “But she wants to say that music was her friend, that it always understood the way she felt, and that it is still important to her. Then she e-mailed me and asked me to tell you that growing up, she felt like Marilyn in The Munsters.”

Alice’s message is less cryptic: “Oh,” Crowe remembers, “my mom wants you to know that she never went barefoot in the house.”

Like those passengers on the Stillwater bus singing “Tiny Dancer,” Crowe found a home on the road, one with a camaraderie that he has never found anywhere else. After moving on and looking back, he still calls his years at ROLLING STONE “the best job I’ve ever had and the best job in the world.” He’s retelling a boy’s story from a time forever gone – but in the right light, through the right window, anyone’s past can belong to everyone.

One last question: Why did you really make this movie?

[Long pause] To say, ‘I remember’ to everyone who helped me out back then. It’s a thank you: Thank you, Ben; than you, Jann; thank you, Lester; thank you, Led Zeppelin; than you, the Eagles…. thank you, India. No, really it is. I needed help back then – getting backstage, learning who I could and couldn’t fall in love with, learning what “off the record” meant, learning to write the stories I had researched pretty well. So it’s a thank you to them and the reason we all got together. You know? Let’s just all fucking say how much we love music. Let’s risk being sweet.

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #851 – Anthony Bozza – September 22, 2000