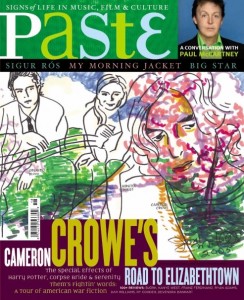

Elizabethtown – Paste Magazine

Cameron Crowe: The Road to Elizabethtown

It’s day three of sound mixing for Elizabethtown, and deep inside Hollywood’s Universal Studios, the Alfred Hitchcock dub stage buzzes with activity. Cameron Crowe and his nine-member team fine-tune the movie’s “very fragile” airport scene, bringing the music up here, taking the footsteps down there, swapping Orlando Bloom’s “um-hum” for an “ahh” to make him sound less cynical. In the midst of this, Crowe and his associate producer Andy Fischer juggle other urgent matters. Over the phone, song clearances are negotiated, screenings are scheduled and taglines are debated with the studio (Crowe worries that one of them belittles Kentucky, so he cuts it from the list). Low’s Alan Sparhawk and Mimi Parker drop by to take in the proceedings. Midday, Crowe is told to expect a call from Van Morrison and to act surprised. “It’s not normally this crazy,” Crowe assures me. (When I return a couple weeks later and Fischer tells me the same thing, I start to question what normal is for them.)

Even though he’s been suddenly thrust into seven-day workweeks to accommodate Paramount’s new deadline, Crowe still has to break from mixing and drive across the studio lot to film a personal welcome for European screenings and promos for online trailers. The room breaks into laughter as he does take after take of “exclusive clip” intros, merely substituting one website for another. Leaving the shoot, he apologizes. “I’m sorry you had to see that. I can’t believe how hard it is to stand in front of that camera. I go right back to the mirror in the junior-high locker room, and you just hate everything you see and you want to be the other person.”

Rushing back to the dub stage, he pauses to introduce me to Melvin, the doorman. It’s business as usual for Crowe—when I arrived earlier, he not only gave me the names of all crew members present, but also their bios. This inclusiveness explains the camaraderie and family vibe on the set. “It comes from loving the team and the work,” he says. “I listen to all the actors, and I listen to grips. I try not to take too much time doing it, but we are a team together.”

What I Really Like is Music

Crowe got his start, not as filmmaker, but as a music-journalist prodigy who—at age 13—was already writing for the San Diego Door. There, he was a sponge soaking up all the knowledge and mojo he could from rock-crit legend Lester Bangs, who took the young Crowe under his wing. Graduating high school at 15, he became a contributing editor at Rolling Stone, where he interviewed luminaries like Bob Dylan and Led Zeppelin. At 22, he went undercover and returned to high school for a full year to research Fast Times at Ridgemont High. Before the book was released, Hollywood tapped him for the adaptation. Since then, his adult life has been devoted to film, where he’s achieved commercial and critical success, including an Oscar for his semi-autobiographical Almost Famous screenplay and a Best Picture nomination for Jerry Maguire.

Nonetheless, some 26 years after leaving Rolling Stone, Crowe claims to have never left music journalism. “I do it all the time,” he says. “When I was doing the research for Elizabethtown, I interviewed My Morning Jacket and Jim James for hours and hours—about their music and about Kentucky and all their relationships with their fathers. I can’t help interviewing.”

Asking questions is a crucial way for Crowe to interact and process information. During our extended chats, he repeatedly stops himself from unconscious attempts to turn the interview around. But he had an even harder time on the Elizabethtown set with singer/songwriter Patty Griffin, who plays a small role. “I’d just walk up to her and be like, ‘Everything going OK with the scene? Yeah? OK. Do you ever play ‘One Big Love’ live?’ I never quite found a rhythm where I could just kind of deal with being a fan and process it by interviewing her.”

Griffin’s 1,000 Kisses actually inspired Crowe’s approach to filming Elizabethtown. “After trying different ways of being creative,” he explains, “she had made the decision to go back to basics and to be real simple and from that came her next breakthrough, creatively. And I wanted Elizabethtown to be a little bit like that. Be spare and from the heart, and without a lot of people being assistants to people who are assistants to other people who sit around. Everyone in the room should be making the movie and not living a lifestyle.”

That attitude seeped into the movie and resulted in the quickest work Crowe’s ever done. “It gives it a kind of an urgency,” he explains, “and some things are messy, but like life. I generally will always love the demo of a song more than the actual labored-over song, and I always find a way to get a hold of bootlegs to see the original versions of stuff that I loved. And so I wanted this to be the original version, with no versions after.”

With Crowe, it always comes back to music. Walking into the offices of his Vinyl Films production company—housed at Paramount—there’s a photo of Crowe with his hero, filmmaker Billy Wilder, hanging inside the front door; down the hall is a framed poster of Hal Ashby’s Harold and Maude; but virtually every other inch of wall space is covered with music memorabilia—photos of John Coltrane, The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Bob Dylan, Nick Drake, Peter Gabriel and My Morning Jacket, as well as photographer Michael Wilson’s What I Really Like Is Music exhibition poster.

More than just a personal passion to adorn his walls (and wrangle into his soundtracks), music is crucial to the way Crowe makes films. When he needed Bloom to loosen up on the Elizabethtown set, he resorted to the language that comes easiest to him. “In band terms, we’ve already got the scene,” he tells Bloom. “You’ve played Madison Square Garden. It went great; 20,000 people were there. Now is the next night. It’s Poughkeepsie; the pressure is off. Now is when you go wild and try all kinds of new stuff. There’s only 3,000 people, and no one is reviewing the show. It’s just for you and the fans. Let’s go there.”

“Music is such an instrument for direction for Cameron,” Bloom says from the set during filming. “He’ll play music during scenes, in between scenes, to quiet us before starting a scene. Each scene has its own theme song; each character has a tune.”

Co-star Kirsten Dunst, who proudly announces that she turned Crowe on to Rilo Kiley, recalls her audition. “He played me this Tom Petty song, and that always gets me. The music of a film really says so much more than anybody can tell you about a movie.”

“It’s really good to know what music they love and what really reaches them,” Crowe explains. “It’s a lot more eloquent sometimes than saying ‘I’m really looking for you to be more… .’ With Orlando, I’d put on Jeff Buckley and he’d know exactly what that meant.”

The Path to Tinseltown

The jump from music journalism to filmmaking wasn’t jarring for Crowe. “To sit in a restaurant and watch people and just write about that—that’s my favorite thing to do,” he says. “It’s what [journalists] do and it’s what I try and do with the movies. You just try to catch a snapshot of what life looks like.”

At Rolling Stone, Crowe covered film whenever he could. “I always wanted to write more as a journalist about film, so it was a big deal when Jann Wenner would give me assignments to write about Sissy Spacek or Richard Dreyfuss.”

Dreyfuss, it turns out, was instrumental in furthering Crowe’s love of movies. During their interview, he started grilling Crowe about his viewing habits. “Do you go home at night and just turn on the TV and watch black-and-white movies?” he asked Crowe, who reenacts the scene with a hilariously spot-on, rapid-fire Dreyfuss impersonation. “Because you should. You should… I’m gonna set up [Frank Capra’s] State of the Union and you’re gonna come see State of the Union and it has nothing to do with this article you’re writing about me, it has nothing to do with that article at all… .”

Crowe continues in his own voice, “I remember watching, going, ‘Boy, there’s an avenue that you can go down, starting to love these movies—that will just go and go and go.’ And before long I was on that path, just taking as much of it in as I could.”

Wanting his cast to travel a similar path, Crowe has enforced a required-viewing list since Jerry Maguire. “You can’t beat sitting an actor down that might not have seen some of these movies and just saying, ‘Check this out,’” says Crowe. “It’s just the cameras on the actors, and enjoy this three-act play that they make out of a simple kiss. When an actor kind of gets that sparkle in their eye and says, ‘I get it. How many more movies did this guy Howard Hawks make?’ You just love to be able to say, ‘I’ll get you a bunch of them, and you should watch them. Maybe they’ll just seep in there somewhere, and what’ll come out will be your version of something that’s sparkling and original and comic and real.’”

The key directors in Crowe’s pantheon are Billy Wilder (“my favorite”), Howard Hawks, Preston Sturges, François Truffaut, Jean Renoir, Hal Ashby and James L. Brooks. Younger filmmakers he sees as continuing the tradition include Wes Anderson and Zach Braff.

Crowe became familiar with Braff because friends kept telling him about Garden State, which involves an uncanny similarity to Crowe’s Elizabethtown script. Both films involve a male lead traveling great distances after the death of a parent, and—essentially—coming to life with the aid of a romantic interest. When Crowe finally saw Garden State, he loved it and tracked down Braff. They instantly bonded over their love for both music and the works of Hal Ashby. “We had a Harold and Maude-loving, guys-traveling-home-for-a-funeral-genre love fest,” Crowe recounts. “I hope more guys write character-based movies about family, with the best music they can find, that’s about getting deep into the texture of your family roots and the beautiful melancholy of all of it. If like one-thousandth of the people that do heist movies weaned themselves from that genre to get into this, I would have more stuff to watch.”

Crowe describes the recurring theme of his own movies as the victory of the battered idealist in a cynical world. As the craziness of day three winds down, I ask him how he keeps that cynical edge at bay. “When I first met Lester Bangs, he said ‘Figure out the thing that makes you different, and it may not always be the shiniest object out there but it will be the thing that was you.’ And I found that celebrating optimism was fun. If there were a zillion movies that were not about that and one or two that were, and I was one of them, I felt like I had a reason to keep going and to tell a story like that. Until it ceases to be how I feel about life, it’s the only way I can write.

“If you’re gonna ask people to spend a couple of hours to see a movie,” he continues, “why not smuggle in a little something that will make you feel good for making it and them feel good for seeing it. Maybe they’ll access something they saw or felt in the movie that allows them to come away with something, as opposed to ‘life is f—ed, and dark is cool.’ Which is the theme of a lot of movies, some movies that I love. But if you can make a movie that allows people to step outside and feel like they can’t wait to just get in their car and drive and just take a deep breath of life—if you can give that to people, why not spend a couple movies doing that?”

Elizabethtown, exit 60b

Getting to Elizabethtown required navigating several detours. Crowe says that after Vanilla Sky, he wanted to do something less about one guy and his head. “I just thought, I want to do a banquet of characters, so I started working on this script—it made a Robert Altman movie seem like a one-man show.” But the complexity ended up being overwhelming and, worse, the story was becoming less and less personal. At the same time, Crowe’s wife, rock ’n’ roller Nancy Wilson, was preparing to kick off a Heart tour in Atlantic City. Despite his reluctance to abandon his characters, Crowe agreed to jump on the tour bus and travel across the U.S., leaving the unfinished script behind.

To his surprise, a day and a half into the tour, Crowe felt the pull of an area he hadn’t visited since his father’s funeral in 1989. “I wake up and outside the window is Kentucky, which is a huge part of our family history,” he explains. “And there were these electric-blue landscapes, and I was listening to music that felt like it was just born to be with these images.”

So the vacationing writer/director said goodbye to his wife and rented a car, intending nothing more than a little relaxation and mind-clearing along the Bluegrass State’s winding roads. “But what immediately happened,” he continues, “was a truly great story arrived, and it was a story about my dad and our whole family tree and what it is to reclaim family roots and meet people you didn’t even know were a huge part of your past and your future. And what it is—when you’ve been living in a box, which I’d sort of been doing—to feel truly alive. It was almost fully formed, almost immediately Elizabethtown. It just felt like a gift had arrived.”

From there, it was an easy decision to walk away from the more complex story, which Crowe barely recalls at this point. “It disappeared into the ether because it just wasn’t real,” he says. “It was an idea of what real life was. It was a movie, and the world is filled with movies.” Now he has a film he says is nearly as personal (and musical) as Almost Famous. Indeed, he calls Elizabethtown the perfect follow-up to Vanilla Sky, “kind of like an acoustic album after having done [Lou Reed’s] Metal Machine Music.”

Elizabethtown centers around Drew Baylor (Bloom), who spends eight years designing a pair of sneakers that stands to lose his now-former employer $972 million. Distraught, having made many “sacrifices for shoe greatness”—including missed birthdays and family Christmases—Drew is on the verge of suicide when his sister calls with news of his father’s death. Flying to Kentucky where his father was visiting relatives, he meets effervescent flight attendant Claire Colburn (Kirsten Dunst). With the consistent prodding of Claire and the chaotic embrace of an extended family he barely knows, he slowly comes to terms with love, family and life itself. The film ends with a road trip across the country—just Drew and his father’s ashes, following a set of meticulous instructions from Claire that include maps, time schedules and specific songs to listen to at specific points of interest. The trip, another of Crowe’s iconic film moments, completes Drew’s emotional journey and ends in an embrace that, in other hands, would prove too much. But Crowe earned this ending with the depth of character that preceded it.

The Heart of Uncool

Happy endings have been a staple of Crowe’s films, and he’s utterly unapologetic about it. Commenting on the fact that his last three films have all dealt with suicide, he says he thinks a lot about Kurt Cobain (whom he never met). “Maybe he was one day away from waking up wondering why he was so f—ing bummed out yesterday. And I always think, ‘What if you’re able to do that for people in some way and make them feel like what they came into seeing that movie with wasn’t as important, wasn’t as lethal, a couple of hours later when the movie’s over.’ And if you can do that at all—by the way for yourself, as much as anybody—then f— whatever anybody says about ‘You were too sweet’ or ‘Why did they kiss at the end?’ They kissed because they kissed, you know? Put on a heist movie next; I’ll watch it with you [laughter]. But this is the movie that ends with mandolins and they kiss and who knows what’s going to happen.”

Crowe is likewise unapologetic about his casting. With leading actors ranging from unknown Patrick Fugit to Tom Cruise (twice) and soundtrack choices from Elton John to Red House Painters, Crowe’s shown a determined eclecticism in actors and music. “It’s like Paste,” he says. “You just make a decision that you’re gonna do the stuff that matters to you and the stuff that you want to put on your own personal throne of appreciation. And you find there are other people like you out there that say, ‘Wow, I can’t believe that this person is like me and will write about U2 and Josh Ritter and Over the Rhine in the same little space of words.’

“In the same way, nobody could understand why we’d cast Kate Hudson in Almost Famous. ‘You’re talking about Goldie Hawn’s daughter? So, it’s like a Hollywood royalty thing?’ No, she came in and won the part because she was great. It’s funny because the same people are going around later saying, ‘Well, I’ve always loved Kate Hudson. She’s fantastic. She turned me down for my movie, but I’ll get her on the next one maybe.’ And you just get this sense of how high school it can be. So really, when you try and be ‘indie cool,’ that’s when you really get caught up not following your heart. And I don’t know, I had a feeling about Kirsten Dunst and Orlando Bloom being real and right for each other in the movie, and that’s why I cast them.”

You had Me at “I’m Fine”

At the beginning of Elizabethtown, as Drew deals with his job travails and then his father’s death, he keeps repeating, “I’m fine.” It’s a crucial line for Crowe, and he’s enamored of Bloom’s delivery. “To say ‘I’m fine’ in all the ways that we say it in life, particularly when we’re not fine, that’s tougher than a monologue that David Mamet has written for you beautifully already. How do you turn ‘I’m fine’ into a monologue? That’s acting.”

Crowe lives for such subtleties. When I ask him about his favorite lines from his own films, he doesn’t go for “You had me at ‘hello’” or even “By choice, man!” Instead, he mentions what he calls the “in-between lines,” like when Drew pulls into Elizabethtown and Jessie (Paul Schneider) says simply “Oh, yeah.” Crowe cherishes “those little things that slip out.”

While Bloom describes the feel of Crowe’s dialogue as improvisational, the performance is far from it. “The way he writes, it’s sort of musical,” he says. “He wants you to get the beat of it, and you have to hit the specific words in rhythm. It’s really offbeat, and it’s kind of awkward to learn because it’s real. You know how sometimes when you’re having a conversation with somebody, how the words come out all skewed but they sort of work—he knows how to do that so perfectly.”

The Journey Home

Crowe calls his family “entertaining heroes” he wants to pay tribute to, but he writes about them with some trepidation. His sister worries about the potential for his movies to exploit the family, he says. “So I try really hard to be personal and write about what’s real but not encroach on her sacred memories and feelings …. I worry about misstepping because I really love my sister and her sense of family. But I sometimes need to write about my family, and she’s a part of it.”

At the end of Almost Famous, William Miller’s mother and sister hug after a brief estrangement. It’s a fantasy in Crowe’s mostly autobiographical story. For years after his father’s death, the relationship between his mother and sister was strained. “My dad was really the glue that held the family together,” he explains. “There was a real rush inside our family to fill that void, trying to find a rhythm to how our family would now work. And my sister was really close with my dad.”

In the end, Crowe’s film helped bring his family together. “There was a period of time after Almost Famous where everything was great in our family,” he says. “In terms of all of us relating, the movie gave us a little bit of a map. And maybe by honoring my dad [in Elizabethtown], we’ll have a new map to work from.”

His experience making Elizabethtown in many ways mirrors Drew’s journey in the film. Crowe’s dad visited his Kentucky family every summer, returning with a light accent, and he accompanied his father as a kid but stopped as he grew older. “I got busy,” Crowe says, “and as in the movie, we always felt like, ‘Well, next summer we’ll go and take that trip to Kentucky.’” Filming the scene with Drew driving cross-country with his dad’s ashes, Crowe says, “I felt like I got that trip back to Kentucky with him. So much of what I’d written actually was there to be mined, and people from my past and his past could actually be with us and help us make the movie. I pretty much felt [my dad’s] presence constantly from day one.” In many ways, Crowe says, the film is a buddy movie. “[Drew and his father] come to know each other. It’s never too late to discover somebody close to you who died, because everybody leaves clues behind.”

Crowe kept digging up those clues throughout the process, going through his father’s belongings and tracking down letters he’d written. “And I found one thing that was amazing,” he says. His dad had written an undelivered letter to him, pitching an idea for his Fast Times at Ridgemont High book. In it, the students find a letter from a deceased Mr. Hand. It’s a “searing, aching, amazing” letter telling his students that the secret to everything in life is family and community. “Page after page after page,” Crowe recalls. “It was more than a pitch. It was really my dad’s message to me. And that was already the theme of Elizabethtown, so it was one of those messages you get when you feel like you’re on the right track.”

Courtesy of Paste magazine – Tim Porter – October, 2005