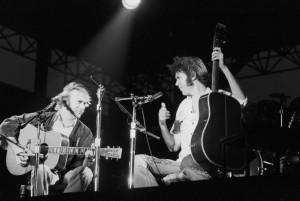

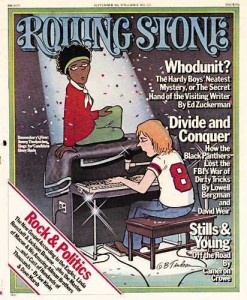

Stills & Young Tour – Rolling Stone 1976

In this new addition to the site, Cameron chronicles the on again/off again Stephen Stills and Neil Young tour for this 1976 Rolling Stone piece. Happy Friday everyone…

Quick End to a Long Run

In which Neil Young and Stephen stills find that old magic and lose it all to a sore throat

Los Angeles – Forget the balding pate and those wisps of gray. Stephen Stills and Neil Young, their hair cut summer-short, looked eerily like they did on the cover of Buffalo Springfield Again. But gone, at least temporarily, was the carefree abandon of those days. This was serious business.

The scheduled three-month-long Stills-Young band tour had been rolling only two weeks, and while it came close to jelling in Boston just a few days before, the show still teetered on the edge of the magic that everyone knew they were capable of.

Even before they broke into their opener, “Love the One You’re With,” the sold-out crowd of 20,000 at the Capitol Center exploded at the sight of Stills and Young on the same stage again. And this, the summer of Aerosmith and ZZ Top, it was nothing short of astonishing to see the sustained drawing power of two artists who have not seen a solo hit single or gold album in years.

On paper, Stills and Young’s set was a fan’s dream. “Love the One You’re With” was followed by a verse-trading rendition of “The Loner,” then “Helpless,” “For What It’s Worth,” the title track of their forthcoming album, Long May You Run, “Black Queen” and ‘”Southern Man.” After a ten-minute break, Young returned alone for “Sugar Mountain,” “Old Man,” a superb new song called “Stringman” and “After the Goldrush.” Stills performed his own solo set of “Helplessly Hoping,” “49 Bye Byes,” “Word Game” and “Four Days Gone.” Together they did an acoustic “Ohio,” then “Buyin’ Time” with the band and another new song, “Evening Coconut,” “Make Love to You,” “Cowgirl in the Sand” and “Mr. Soul.” The encore was an electric “Suite:Judy Blue Eyes.”

Aside from the power of the song themselves, though, it was another off performance. Still had difficulty singing on mike and sometimes even remembering words. The harmonies sounded ragged. Young, in the process of keeping the vocals faithful, became too tense to cut loose on guitar himself. In typical style, Young did not hang around afterward. He went straight from the stage to the airport, where a Lear jet would take him to Miami for a day of remixing some vocals on Long May You Run. “If we both go,” he told Stephen, “neither of us will want to come back.”

Stills spent the rest of the night in the Holiday Inn bar, nursing drinks and talking with fans. Somewhere in the early morning hours, he was even coaxed onstage for jams at the house band on “The Thrill is Gone.” Less than an hour after he finally headed upstairs to retire, the morning paper’s review was out. The assessment was more bewildered than negative. Like most every other review thus far, it wondered why Young had ever taken on such a project.

Neil Young refused to be quoted in connection with the Stills/Young band tour. He expressed a strong desire to just do the tour, bypass the hype and move on. He was fully aware of their ever-diverging paths, but he respects Stills as a musician . . . and worries about him. This tour, one sensed, was Neil’s way of helping Stephen back on his creative feet. “It was,” said one associate, “something Neil felt he had to do.”

At 30, Young has begun more than ever to realize his potential. Besides working on a screenplay, he write several songs a day, has a few complete albums in the can and maintains an entirely separate career with Crazy Horse.

Stills, now 31, knows full well that his solo work has lack critical importance in recent years. “These last two years,” he said, “I’ve been concentrating on my guitar work. I want to be considered one of the masters.” As result, the emphasis has gone off what was once Stills’s strongest area – songwriting. When his last album, Illegal Stills, was ignored in most circles, including Rolling Stone’s review section, he was very disappointed, but he said recently, “I’ll tell you something. I’m gonna keep at this until I win back every last person.

“If I’m cruddy on my own, it doesn’t bother me half as much as if I don’t hold my own backing up Neil. The one thing that everyone has always assumed is that there’s a fundamental competition between us. In fact, it’s the difference between us that makes it work. When he comes up with those killer lines, I fall on the floor just like everybody else. And when I play something that blows his mind, he falls on the floor just like everybody else. It’s the ultimate complementary relationship.”

The changes which that relationship has undergone must strike Neil as ironic at times. Stills was the one who brought him into Buffalo Springfield and later Crosby, Stills and Nash. Young, at that point, with little more than a hired gun – another electric guitar to toughen up CSN’s sweetness-and-harmony image. Young caught on quickly. Today, it’s that same hired gun whom everyone expects to call most of the shots. Whenever CSNY tries at another reformation, it is usually because Neil has expressed interest. But – and here’s the snag – Neil Young is not a pressure performer. His constant frustration is that he must stand in a spotlight.

“I could have dug playing guitar with the Eagles,” Neil blurted late one night in the customized bus he designed himself. He jammed with the band three years ago at a San Luis Obispo benefit and never forgot how much fun he had. “I’d join any band I got off with. I’d love to play with the Rolling Stones . . . but they probably don’t know my rock & roll side.”

It’s that same guitar player in him that brought Neil Young back to Stephen Stills last summer. Young had just been released from the hospital after a throat operation when he dropped by a Stills concert at the Greek Theater in Berkeley on July 25th. He could not speak, much less sing. “It was truly great,” Stephen remembered. “He was passing us notes and playing up a storm. We both got off like motherfuckers.”

Neil did not forget. Four months later, he “just showed up” backstage at Stills’s Stanford University appearance. Neil watched the show and finally wandered out for the acoustic set. When he turned up the next afternoon in Los Angeles for Stephen’s concert at UCLA’s Pauley Pavilion – again without warning – Young was equipped with his electric Les Paul. He and Stills dueled guitars far into the night, dazzling themselves and the audience to no end. “The spirit of the Springfield is back,” Stills shouted in ecstasy. The commitment has been made.

Young went on to play a few northern California bars, then visited Japan and Europe with Crazy Horse. The tour, by every account, soared beyond Neil’s highest hopes. “Every night was incredible,” he recalled. “I really get free with Crazy Horse. They let me zoom off . . . and know me well enough to be right there when I get back. They’re the American Rolling Stones, no doubt about it.”

When it came to America, though, Neil returned to Stills. The two flew to Miami and began work on an album. Midway into the sessions, Young had the impulse to turn it into a Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young project. Crosby and Nash agreed to give it a shot and flew down to Criteria Sound Studios to help out. For a few weeks it looked as if that third CSNY album would finally become a reality. Then, while Crosby and Nash took a break and returned to L.A. to meet the deadline for their own sessions on Whistling Down the Wire, Stephen and Neil continued working. They eventually decided to return to the original idea of the Stills/Young band. Crosby and Nash’s harmonies were replaced by Still’s band.

Said Graham of the near CSNY reunion attempt: “We probably came closer this last time than we’ve ever come before. Stills was amazingly loose. Neil was great. I just have to say that I deeply resent David’s and my vocals being wiped off the album. That hurts me. The four of us together have a special power . . . we make people happy with our music. The fact that we deprive people of that happiness by acting like children really bothers me sometimes. I don’t care what anybody says, there’s room for CSNY just like there’s room for anything else we might want to do.”

As for another go at CSNY, Graham admitted, “I’m not closed that idea.”

Neither is Crosby. “Look,” he said, “here’s what it’s like. If you were crawling through the desert and knew of a place where there was once a luscious fucking well . . . you’d go back to see if it was still there, wouldn’t you?”

Stills, too, didn’t close the door on some future reunion of the four: “The last thing I want is to have Graham Nash and David Crosby as enemies. But this Stills/Young album . . . I don’t know, we just had to do it ourselves this time. No Richie Furays, no David and Grahams, no nobody between us.”

After finishing everything but the final mixing of Long May You Run, Neil Young and Stephen Stills took to the road together. Both canceled solo summer commitments,. Although it wasn’t Stills’s band (George “Chocolate” Ferry on bass, Joe Lala on congas, Jerry Aiello on keyboards and Joe Vitale on drums), the tour was the same one originally intended for Neil and Crazy Horse.

Following Washington D.C., the next show, a muggy outdoor affair in Hartford, Connecticut, was unquestionably closer to the mark. The album now entirely finished, the band relaxed into a comfortable pace. The harmonies remained ragged but by the end of the set, Neil and Stephen’s slashing guitar work was near-flawless. Stills, just after leaving the stage, gushed: “There’s no place I’d rather be than right here, playing with that guy.”

Neil caught him in a bear hug, hopped in his bus and headed for Cleveland to beat the traffic.

On board his own bus – a more standard travel-only model he rents from Young – Stills spent the ride listening to Long May You Run. He was proud of the album, unabashedly claiming it to be his best work in years.

“There is one very special thing that Neil and I do for each other,” he laughed. “Every time we play, I learn a little bit more about being real and he learns a little bit more about the polish.”

By the night of the Cleveland show, Stephen was ready to kill. He ripped into “Love the One You’re With” with an urgency that hadn’t surfaced since he’d written it. Neil responded with a blazing solo in “The Loner.” Stills came back with a chilling delivery of “For What it’s Worth” . . . and on it went. Suddenly, they were beyond the smiles and the backslapping. The Stills/Young band bore down for a snarling night of what they’d all been waiting and hoping for. The magic.

Standing onstage during Neil’s solo, Stills was enjoying the long overdue taste of victory. What happened? “Neil crawled all over me,” Stills chirped. “He snapped me awake. I guess I was flaking it a little bit, so he jumped on my ass.”

After the show, Neil was similarly jubilant. Alive and animated, he told Stephen not to consider the Cleveland show a peak. “Think of it,” he coached, “as a new standard. Something you can’t dip below.”

Visiting the hotel bar before hitting the open road for Cincinnati, Neil raised a toast. “Here’s to the return of Stephen Stills.”

The next night in Cincinnati, Neil let Stephen Stills run with the ball. Stills delivered. The roughest part of the set for him – following Neil’s show-stopping “After the Goldrush” with his own acoustic set – was a breeze. Stills sat down and began gently playing the chords to “Helplessly Hoping.” We it came time for the vocal, gone was the whiskey wheeze of old. Singing slowly and into microphone, Stills let the audience fill in the lilting harmonies themselves.

Neil studied the sight, glowing like a proud father. “Now,” he told the writer, “you have something to write about.”

It seemed the proper place to bow out and do just that.

Three concerts later it was over. Pittsburgh, Greensboro and Charlotte had been good shows – great by some accounts – and Young was reportedly pleased with each one. By Atlanta, though, a recurring throat illness had silenced him. Young flew home to California, was told to rest by his doctors, and went into seclusion at his Northern California ranch. Rumors immediately pegged the tours cancellation as intentional, and Young hasn’t taken any phone calls or had any visitors.

Stills’s reaction to the aborted tour: “I learned a lot and had a lot of good times. I don’t think they’re over, and I’m just not going to let this set me back.”

In the meantime, both have canceled all appearances the summer. Young had a tentative ten-date tour with Crazy Horse scheduled for November, just about when he’ll release his next album, Chrome Dreams. Stills, recently sued for divorce by wife Veronique Sanson, is planning a fall tour with stalwart guitarist friends Chris Hillman and George Terry.

After that, Stills may well take a few years off to write a book and relax. “My hearing has gotten to be a terrible problem. If I keep playing and touring the way I have been,” Stills shrugged, “I’ll go deaf. I want to take care of myself and be around for a while . . . ”

What Neil has fulfilled or abandoned his drive to revive the affiliation with Stephen Stills is unknown. With Long May You Run just out, Stills is confident that he has not seen the last of Young.

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #221 – Cameron Crowe – September 9,1976