The Marshall Tucker Band

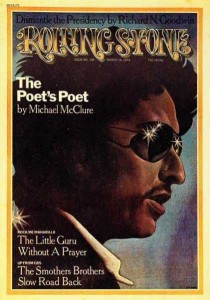

Cameron talks about the rock and roll business with the Marshall Tucker Band for this 1974 Rolling Stone interview. Happy Tuesday everyone…

Marshall Tucker: The South Also Rises

Atlanta, GA – It’s Friday night and Richard’s, the lively hotspot of Atlanta’s rock-club scene, is jumping. Onstage, a local favorite is grinding out rock raucous blue standards. The dance floor is an euphoric mass of squirming young bodies.

Welcome to the great lost teenage innocence. David Bowie may set the coasts afire with his 36 costume changes and the New York Dolls can mincingly sing of decadent trauma, but for this typically well-scrubbed Southern crowd, “drag” is when you’ve waited too long to buy your Allman Brothers tickets.

“That glitter shit,” drawls one sweat-drenched regular, “is for the people that don’t care about the music, dontcha think? Here in the South we got our own bands who don’t need any of those…gimmicks. Like Lynyrd Skynyrd or the Marshall Tucker Band or, acourse, the Brothers. Man, they just get out there and fuckin’ play.”

“Until just lately,” said guitarist Toy, Caldwell, focal point of the Marshall Tucker Band, “if you were a Southern band, the best you could hope for was work at a local bar playing the Top Forty. Before the Allman Brothers, hell, there wasn’t anybody making it from these parts. Then came Wet Willie and Cowboy…and now even groups like Hydra and Lynyrd Skynyrd are finally getting their break. People are really starting to listen.”

The Marshall Tucker Band has scored a rare rock & roll coup. Unknown less than ten months ago, they religiously followed the Phil Walden (president, Capricorn Records) game plan of constant, year-round roadwork. Today, their debut album, released last April, has sold over 300,000 copies and, after 29 weeks of the charts, the album is still lingering in the low numbers of the national LP charts. With the skyrocketing second album, A New Life, Marshall Tucker is the South’s second most popular band.

“I don’t know that much about album sales and stuff,” admitted Caldwell, a little dazed, “but we sure didn’t expect the first record to sell that many copies. We were six musicians that, man, nobody ever heard of. We had hardly played live at all before the album came out, so we had no advance following. We sold this band through our own constant touring. We went out there night-after-night and played our asses off.”

The primary composing force behind Marshall Tucker, Toy Caldwell writes tunes much in the traditional Allman style. “Before we were signed, we knew of the Brothers just vaguely. I’d heard of them, but I’d never really listened to them that much. See, the only records I listen to are hard-country records. Tell you the truth, I feel weird listening to albums because I’m very impressionable. If I hear a lick or something I really like, I’ll be playing the guitar and before I know it I’ll be playing the shit out of it. It must be a subconscious thing. I try to stay away from music as much as I can. I hardly ever listen to the Allman Brothers. I try to miss their set if I can. ”

Toy and his bassist brother Tommy are deeply rooted in the back-porch picking-country atmosphere of Spartanburg, South Carolina, where they’ve lived all their lives.

“Our father loved country music,” he said. “He even had a band together that played at square dances. We always would come along with him and watch him play. We grew up in that environment of country and bluegrass. Tommy and I have been playing together since we were about 11. We had a guitar duo that was pretty popular. Our parents had us play at parties. Then the Beatles came out and all of a sudden we’d play our Hank Williams tunes and everybody would leave. I started listening to the Beatles to find out what all the commotion was about.”

It was not long until an enlightened Toy formed the Rants, giving the town its first taste of rock & roll. “And we were into the heavy stuff… the Stones, the Yardbirds, you name it. My father, needless to say, thought we were crazy.” The Rants raged across the regional teen-club discotheque circuit for nearly three years until Uncle Sam took the band on an unexpected road trip.

“Everybody got drafted, went into the service about the same time and got out about the same time. I didn’t mind the Marine Corps. I guess it’s something everybody’s got to go through once in a while. I didn’t really have much of a choice. We all saw each other when we came home for the holidays, but we lost all communication during that time. Although I didn’t get a chance to play at all, I had already decided that I wanted to be a musician. I got out in April ’69 and started a band called the Toy Factory. We gigged around for a couple of years.”

The Toy Factory was a labor of love. Traveling the discotheques was certainly not a major money-making venture, and to stay afloat all the members kept their day jobs. Toy, for example, sheepishly admitted to being a plumber. “What can I say? My father owns a fairly big plumbing company here in town and I worked for him. Plumbers get paid good, you know. If you’ve got a commode full of shit, you ain’t gonna get somebody to stick their hand down there for very cheap. God almighty.”

Working all day and dutifully playing the hits all night began to breed discontent. It was one cold Southern night several years back when a frustrated delegation of Spartanburg rockers decided to quit moonlighting and join forces in one all-out try at self-sufficiency on their own terms. Enter the Marshall Tucker Band. Named after the long-dead owner of their rehearsal hall, the quintet (drummer Paul Riddle was added just prior to the first LP’s recording) consisted of ex-Rant George McCorkle, ex-Toy Factory men Doug Gray and Jerry Eubanks and the Caldwell brothers.

“We didn’t play gigs at all for about six months,” said Toy. “We just concentrated on working up original material and making some good demo tapes. Shit, the first place we went loved ’em.”

The band was playing on the bill with Wet Willie at a local club called The Ruins. Wet Willie, a Capricorn act, was enthused enough to instruct Marshall Tucker to leave a demo with Phil Walden. “Hell,” Caldwell grinned, “we never heard of the cat, but we drove to his office in Macon one day to give him the tape. He wasn’t there and we got the same old shit – ‘Leave your tape and we’ll listen. Don’t call us, we’ll call you….” We’d do anything, we didn’t care, so we threw it on Frank Fenter’s [Capricorn’s executive vice president] desk. Naturally, we didn’t think he’d ever listen to it. He called us up the next day.”

Capricorn booked the group into Macon’s Grant’s Lounge for a private audition. The Allmans were impressed and Walden was dancing in the aisles. The Marshall Tucker Band were signed the next morning.

To coincide with the release of The Marshall Tucker Band, the group was temporarily assigned to an opening act position on Allman Brothers tours. “It would be a flat-out lie to say those tours weren’t incredibly important to us,” said Toy. “It’s the greatest exposure you could possibly have. The Allmans like to play with us; it’s good for both of us because our music is somewhat linked. The audience is really gonna like what we do if they like the Allman Brothers.”

Greg Allman is calling them “a ferocious band, so good they’re scary” and the record company is ecstatic over their “new headliners.” Meanwhile, Toy finds the whole thing… well, very nice.

“Everyone tells me that this rock & roll business is ‘gonna fuck you over’ and that it’s a nasty way to earn a living. I don’t know, everywhere we go we’re treated like good old people. Everybody’s been so kind to us, we feel at home just about anywhere we play. I can see how this business could make you crazy if you let it, but then I guess that’s one of the advantages to living in Spartanburg.”

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #156 – Cameron Crowe – March 14, 1974