Happy Birthday Linda Ronstadt!

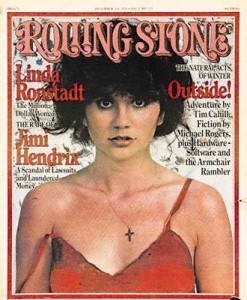

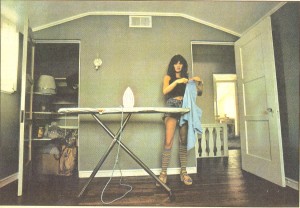

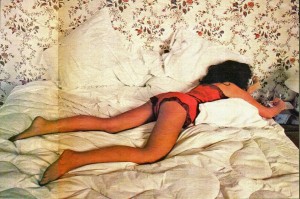

We want to wish Linda Ronstadt a very happy birthday today. Let’s celebrate with a look back at her December 2, 1976 Rolling Stone cover story with Cameron. Pictures were taken by the amazing Annie Leibovitz.

Linda Ronstadt: The Million-Dollar Woman

LOS ANGELES- “Miss Ronstadt’s line is busy. You’ll have to wait. I gotta check you.” The beefy guard at the front gate of Malibu Colony waits and dials again. Still busy.

Twenty minutes later, the guard gives up and waves me through. “You could be here all day,” he cracks mirthlessly. “But listen . . . if I don’t hear from her within five minutes” . . . he pauses for effect . . . “you’ll meet the sheriffs. You don’t want to meet the sheriffs.”

The Colony. A tract of roomy beach houses strung along the Pacific 25 miles north of Los Angeles. Considering the surroundings, it’s not surprising that Malibu has almost always been inhabited by artists, though the enormous cost of year-round, triple-security living makes it a select few at that.

The Band built their studio here. Dylan, Neil Diamond and Eric Clapton recorded here. Neil Young named Zuma after the Malibu community where he lives. Joni Mitchell refers to it in “Trouble Child” . . . and Linda Ronstadt posed for the softly erotic cover of Hasten Down the Wind just outside her picture window.

I pull up in front of her wooden gate and push the intercom button. A frenzied voice blurts, “Uh . . . hold on . . . c’mon in . . .” and the gate buzzes open.

A minute later Linda Ronstadt, who turned 30 last July, bounds down from her upstairs bedroom. Hair mussed and still in a nightshirt, she rubs the sleep from her eyes. It’s one in the afternoon. “I’ve been on the phone all morning,” she says. “Let me make some coffee.” I almost forgot to explain about the sheriffs.

Her eyes widen as she listens to the story. “That guard said that?” she asks incredulously. “What a jerk. I better call.” After inviting me to look around, Linda scampers back to the phone.

Her split-level home, which she purchased for almost $200,000, dominated by the Pacific Ocean and beach only a few yards below, is roomy, with wood floors, plenty of windows and virtually no furniture besides a piano, stereo and blue paisley couch. Linda has lived here alone for the past nine months, and repeatedly apologizes for the lack of furnishings.

“I’m learning to live by myself . . . and I love it,” she says a few minutes later, curled up on the sun deck sofa. “I lived alone for two months once, in an apartment, but I’ve always either been on the road or shacked up with one guy or another or living in some kind of hell.” She leans back into a stream of bright sunlight. “I’ve gone a long time now without falling in love and without having that neurotic tendency to define my existence.”

The overwhelming popularity of Linda Ronstadt has caught more than a few people by surprise. For six years and four albums she was regarded as no more than a barefoot, braless, pleasant-sounding country-ballad singer. Then suddenly, she cut “You’re No Good,” a mainstream pop effort stronger and more confident than anything she’d ever recorded. Her 1974 album, Heart Like a Wheel, shot past Led Zeppelin and Elton John to the top of the charts. Her next two albums, Prisoner in Disguise and Hasten Down the Wind, have also been million-sellers, helped along by singles like “When Will I Be Loved,” “I Can’t Help It if I’m Still in Love with You,” then “Heatwave” and “That’ll Be the Day.” Now, just two years after “You’re No Good,” Elektra/Asylum has compiled Linda Ronstadt’s Greatest Hits for Christmas release.

“When Heart Like a Wheel went to Number One,” says Linda, “I just walked around apologizing every single day. I could see that my supposed friends resented me. I went around going, ‘I’m not that good of a singer. . . .’ And I got so self-conscious that when I went onstage, I couldn’t sing at all. It almost made me go crazy . . . I mean I needed a lot of help, you know.”

Although she rarely looks me in the eye, focusing instead on couples and dog walkers on the beach, Linda’s confessions begin to flow easily. Almost as if I were her analyst.

“I found a psychiatrist,” she continues, “who really put me on the right track. He got me through all those little obstacles. If it wasn’t for him, I probably would have quit . . . I didn’t want to live and I didn’t want to sing again. But I feel stronger now than I’ve ever felt. This is not my fantasy of what I want to be, but it is the reality and it’s a lot more comfortable to live with.”

Linda’s fantasy began in Tucson, Arizona, where, at age 14, she began singing in a folkie group with her older sister and brother. In 1964, at age 18, she left for Hollywood with $30 in her pocket and joined a folk-rock group that became the Stone Poneys. After three frustrating years they broke up, just before “Different Drum” became a hit. As a solo, Ronstadt fronted numerous transient musicians, among them Glenn Frey and Don Henley, who went on to form the Eagles. Linda was unable to communicate with them on musical terms, she says, and she had difficulty bossing men around. “When I got to L.A.,” she says, “I was so intimidated by the quality of everybody’s musicianship that instead of trying to get better, I chickened out and wouldn’t work.” She also had problems with her first solo albums- “I didn’t know what I was doing,” she says. Her producers among them John Boylan and J.D. Souther- would also be managing her or living with her, so that she was at once a singer, a lover, a daughter-figure and a puppet.

Finally, in 1973, she asked Peter Asher, the former pop singer (Peter and Gordon) and the producer of James Taylor, to help complete her Don’t Cry Now album. On the road, anxious to please Asher, she brushed up on acoustic guitar, took command of a ragged band and, in short, grew up. Heart like a Wheel was next. Asher is now her manager and producer.

“Peter,” says Linda, “was the first person willing to work with me as an equal, even though his abilities were far superior to mine. I didn’t have to fight for my ideas. I thought I couldn’t understand machines, you know, and it turns out that the joke’s on me. I finally realized, ‘Gee, I can learn about digital delay . . . .’ All of a sudden, making records became so much more fun. I used to get so depressed when I was in the studio that I would slither under the console and go to sleep with the monitors blaring. Just to escape.”

“For the first time,” Peter Asher notes, “Linda feels more in control of her career, she knows when she has a month off, when she has to do an album. She can see a pattern, a kind of reality to things. It’s more like working for a living, as opposed to going through all the craziness. Before, she always felt that events were just rushing her along . . . in a direction that was really up to the wind.”

These days, Linda has the plucky air of a seasoned professional; and she has matured, as an artist and a woman. Ronstadt may still not be the sex goddess her album-photo-infatuated fans lust for, but she’s getting closer.

Linda’s stage attire has become more refined, too. Her standard Levi’s and white blouse tied at the waist are frequently replaced by long, flowing dresses and halter tops.

But Ronstadt has quirks in her stage presence. She’ll smile sweetly after a song, curtsy and then chirp, ‘Didn’t the Jerry Lewis telethon last night suck?’ Her onstage confidence has grown considerably, and she projects success, helped along by applause from the audience, every time she begins a song.

Still, Ronstadt has hours of horror stories of stage terror and tearful backstage scenes dating as recently as the outset of her tour earlier this year. “I threw up on the way to the airport . . . and for the first two weeks of the tour. I had taken six months off because I’d become a physical and emotional wreck, and now I thought I had an ulcer. I just didn’t think I was good enough. Finally, I just went, ‘Okay, I can go home and forget about it and get sued by every agent and promoter in the world and be completely unprofessional, or I can say, ‘Look, it can’t get great in a month but I’m going to do a little better every night.’ By the end of the tour, a month later, I was looking forward to every night.”

But, she adds, “Believe me, things are not hunky-dory. They haven’t invented a word for that loneliness that everybody goes through on the road. The world is tearing by you, real fast, and all these people are looking at you like you’re people in stars’ suits. People see me in my ‘girl-singer’ suit and think I’m famous and act like fools . . . it’s very dehumanizing.

“I think it’s helping each other out that makes it bearable. The only way to deal with it is to have that real close camaraderie and to keep recycling it and teasing and keeping the humor level up all the time. You have to do it in an aggressive manner, though, or else it turns ugly. It was like group therapy, only worth more.

“When we came back to end the tour in L.A., I had my first feelings of a letdown. Suddenly, all these people weren’t down the hall and you can’t all sit around and drink coffee. We were so lonely that we turned to each other, then they all went home to their old ladies and I came home to the dog, you know.”

It’s very easy to become drawn in by Linda’s tales of intense vulnerability, though Ronstadt has obviously been drawing on some kind of strength all these years. “Anybody can hurt my feelings; it’s not very hard to do. But they don’t get a second chance. I am not a professional victim, and there’s plenty of those in this business because they see vulnerability as something attractive. If I see that someone or something is going to hurt me, I’ll get the fuck out of its way. It’s too easy to get destroyed. But, yeah, I worry. I try to walk that fine line between being strong and trying to avoid becoming callous. As soon as you’re callous you not only shut out all the pain, but all the good stuff too. You either close the door or you open it. I keep the door open with the screen door slammed . . . and a strong dog at the door. That’s the policy of my heart.

“When I first started doing this,” she muses, drawing her legs up close to her chest, “there weren’t really any other [rock/pop] women singers, except for Maria Muldaur and Grace Slick. But Maria was the only one I really knew and neither of us could afford to go to psychiatrists then. Nobody had gone ahead of us and broken any of the ground on the kind of emotional problems that you experience being a woman in this particular place.

“I had a woman cousin at Yale, one of the first women to graduate . . . and they studied these women very carefully and found that they developed all these masculine mannerisms . . . in other words, they completely succumbed to the peer-group pressure in order to get recognition and acceptance. They all began to walk like a man. They began to cop butch attitudes, you know, and that’s what’s happened in this male-dominated business. I felt it happening to me and I decided to strike that from my personality. I like being a girl.”

Another valuable lesson she’s learned, she says, came from Dolly Parton. Emmylou Harris had called Linda over for some vocal and moral support when Parton dropped in on her sessions. They’ve since appeared together on Parton’s syndicated TV show and become friends. “I’ve never met anybody so free of neurosis as that person,” says Linda. “I was devastated by her honesty and her charm and sweetness. I’m sort of this Northern thinker and she’s just kind of a Southern magnolia blossom that floats on the breeze. But she’s no dummy.

“She taught me that you don’t have to sacrifice your femininity in order to have equal status. The only thing that gives you equal status with other musicians is your musicianship. Period. It doesn’t matter how butch you act, how much dope you can take or how many nights you can stay up in a row.”

Linda has been widening her circle of musician friends, too. Phoebe Snow and noted session vocalist Valerie Carter- whom she’s helping record a solo album, giving emotional and vocal support- are recent acquaintances. Snow turned her on to Charlie Parker and jazz singing. “I intend to do some heavy hanging out with her,” Linda laughs. “It’s another sphere of music to drag in.”

When Mick Jagger turned up at her recent shows at the Universal Amphitheatre, she was as surprised as anybody. She brought him to the Valerie Carter sessions, where they hooked up with Lowell George and sang all night. Contrary to rumor, Ronstadt and Jagger did not discuss a one-shot duet album. “But maybe,” she giggles, “I ought to write up a resumé.”

Meanwhile, Ronstadt’s accolades pile up. She didn’t bother to show up and collect her Best Female Vocalist award on Don Kirschner’s Rock Music Awards show (she called them the “Who Cares” awards). “My attitude is, ‘Don’t give me an award, send me money.’” She doubles up with laughter. “I know how good or bad I am. An award won’t convince me that a record that I didn’t think was good is good.”

The doorbell rings. It’s Wendy Waldman, another friend, dropping by to spend the cool late afternoon at the beach. The two immediately talk music, Linda rushing to a cassette machine to play a rough cut of a duet with Valerie Carter. “It’s such a thrill,” she gushes, “to sing with someone this incredible.”

Waldman listens intently to the beautifully intertwined voices- Carter, the unharnessed youngster, and Ronstadt, the polished veteran.

“What do you think?” asks Linda.

“She’s really good,” Wendy says. “She’ll learn . . . just like you.”

Linda smiles and stares at the cassette player. Then the intercom buzzes with my 4 p.m. lift and . . . the phone starts ringing again. “Oh God,” shrieks Linda, “I’m not even dressed yet. I always forget to get dressed.”

Courtesy of Rolling Stone – Cameron Crowe – December 2, 1976