Peter Frampton: Year of the Face

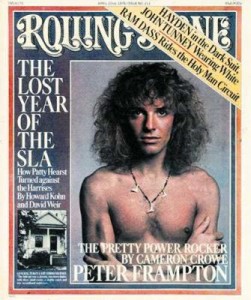

We are back today with a new addition to the site. This is Cameron’s 1976 Peter Frampton Rolling Stone cover story entitled, Year of the Face.

By this time, Cameron and Peter had already collaborated on an August 1974 Rolling Stone story. In the 1977, Cameron would pen liner notes for I’m In You, but today’s 233rd Journalism article focuses on Peter’s meteoric rise. Enjoy!

Peter Frampton: The Year of the Face

It’s like stepping into a scene from Blow Up. The white walls of Francesco Scavullo’s Manhattan photo studio are covered with Black and white portraits of blank-expressioned models. Young male assistants scurry around, each of them trying to act more hassled than the next. “I am not smiling,” whines one. “Streisands’s new hairstyle? Please.”

In another room, looking very much out of place, 25-year-old Peter Frampton waits to have his picture taken for the cover of ROLLING STONE. He squirms while a makeup man dabs colors on his cheeks and eyelids, readying him for a session with one of the world’s most renowned fashion photographers. It’s all happening so fast. Three months ago, Frampton was just another hard-working British rocker, crisscrossing the country with a four-album repertoire. Today, he is the brightest new star of ’76.

If it is Peter Frampton’s year, this must be his week. Only yesterday he returned from a ten-day vacation in St. Thomas – his first rest from the road in three years. His fifth album, Frampton Comes Alive!, was Number One (with a bullet) in two out of three trade listings. Bill Graham had to add a second Frampton concert at the 50,000-seat Oakland Stadium. The first sold out in several hours, as did most dates of his current tour.

I wonder if I’m dreaming

I feel so ashamed

I can’t believe this is happening

to me

“Show Me the Way”

Frampton pries himself away from the makeup man to greet his visitor. “You mean you still recognize me?” he jokes a little uneasily. “I’m in such a daze. Do you believe all that’s happened? Number One? Do you believe it? What a giggle.” He is quickly led before the camera and the blitz-clicking is on.

“He’s gorgeous, isn’t he?” marvels another Scavullo assistant. “Helen Reddy flies us all to Los Angeles, pays a fortune and begs Francesco to make her look beautiful. This kid waltzes in wearing Levi’s and beats them all.”

Photo sessions, especially ones where he is made up and ordered to “look sexy,” drain the slight guitarist. A few days later ROLLING STONE’s art director would decide against using the glamorous Scavullo photos on the cover because he felt they were not quite compatible with Frampton’s personality. “I don’t walk around like this, not even onstage,” Frampton says. He embraces himself and juts out a pouting lower lip. “What’s wrong with smiling? Especially now . . . “

After seven years of tireless touring (two of them as second guitarist in Humble Pie, five as a solo artist), Frampton deserves to wear his infectious smile more than ever. He’s finally struck pay dirt and cannot find a big enough superlative to tell you how knocked out he is, how incredible it feels, how much his head is spinning. It must be the high point of his life.

Frampton agrees. “I was asleep when Dee [his manager, Dee Anthony] called up to tell me we’d gone to Number One. He usually calls up and says, ‘Peta, it’s Dee,’ imitating an English accent. But this time he didn’t say anything except ‘we’re Number One’ in this cracking, emotional voice I’d never heard before. I was really moved. It was so fantastic. I called my parents in England and woke them up because of the time difference. I didn’t cry . . . but I sure came close.” He looks down at his spindly hands. “I’m shaking just talking about it all now. It’s very, very emotional . . . but then people are . . . people are buying my life when they’re buying those records. I hate to sound bigheaded or something, but that’s the reality of it. Suddenly, everything you’ve been doing means something.”

For Dee Anthony – currently celebrating is 25th year in the business – Frampton’s new status is more proof of the adage he’s held ever since road managing Tony Bennett in 1952 . . . take your music to the people. It’s no coincidence that most of Anthony’s biggest acts have broken wide open with live albums – Humble Pie, Emerson, Lake and Palmer, the J. Geils Band, Joe Cocker and Ten Years After. From his office at Bandana Enterprises in New York, the hulking manager works his bands twice as hard as any of his contemporaries. “Sooner or later,” he explains, “it pays off.”

All those around him feel that success has completed Frampton in many ways. Most noticeable is his newfound self-assurance. “It’s so good to see him this happy,” says a friend. “He was putting so much of himself on the line, between the records and the concerts, that when he didn’t quite break through very big you could see it was getting hard for him not to take it personally. Such a sweet guy . . . “

“Sweet guy” . . . “nice kid” . . . nobody has anything bad to say about Peter Frampton. He is extremely easy to like. An already endearing personality combined with the automatic courtesy that comes with all the second-billed years on the road have made him expertly charming. In conversation he remains light and breezy, but his personal life comes out in the albums. “I write about what happens to me,” he says. “It’s all there. I couldn’t do it any other way.” Wind of Change, for example, was a pleasant slice of life from the time of his first marriage. Frampton’s Camel was a depressing look at the marital breakup. Somethin’s Happening marked the arrival of his current girlfriend, Penny, and Frampton was a joyous testimony to their success together.

Before the now platinum Frampton Comes Alive!, none of his albums had gone beyond the 200,000 sales mark. Why the sudden fever? Peter isn’t about to question his explosion to the top: “Dylan, Chicago, Paul Simon . . . and me?” Rather, he shrugs in wonder. “I’ve figured it out,” he laughs. “There’s no way anybody could like that album and hate my guitar playing. That takes care of a lot of my insecurities.

I’ve always wanted to be the best guitarist in the world, ever since I was eight years old. Ever since I saw Buddy Holly and the Everly Brothers and . . . anybody else with a Stratocaster. But between you and me, I’ll settle for just being listened to.”

However enthusiastic, Frampton is actually in the throes of his third blast of superstardom. His first came with the Herd, a short-lived and overly eulogized pop band from the ’67-’68 British boom. After years of juggling studies at Bromley Technical High School, where his father was a teacher and the pre-Bowie David Jones was a fellow student (they both played Buddy Holly songs at the school talent show), 16-year-old Peter accepted an invitation from a classmate, bassist Andrew Bown, to play lead guitar for the Heard – a welcome alternative to being packed off to music school, the preference of his parents.

The band started out playing jazz. “It was great for a while,” Peter recalls, “but even then I realized, oh-oh, I’m appearing on TV every week with my guitar slung over my back, most of the guys in the group aren’t playing on the records and I’m out there singing, which isn’t exactly what I do best. Whenever we played live, I got screamed at so much that nobody could possible hear the guitar. That’s when I began to realize that my face could get in the way of the music.”

It did, and after a run of hit singles, the Herd was a full-fledged band with teen idols. Young Peter, with his innocent schoolboy looks, was named the Face of ’68. It drove him to alcoholism. “I joke about it now,” he says, “but it was getting pretty serious at the time. Between Bown and myself, we’d down 19 triple Scotches a night at the Marquee Club. Maybe not that much, but we never could stand up too well when we were playing. All those screaming girls – they didn’t know we were smashed. And the same guys every week for 18 months just got a bit nervy. Nervy is definitely the world. We used to reverse the numbers, do them backwards – anything to break the monotony.”

A year later, though, the Herd broke up to find they had been “royally screwed.” As minors there was little they could do about their due monies except learn a lesson. Until recently, Frampton never passed up a chance to malign his former mangers, but now his attitude has softened. “I’m tending these days not to regret anything. If it had anything to do with reaching the point I’ve reached, it was worthwhile.” Frampton laughs heartily. “And believe me, I never thought I’d be saying that.”

Although the name was coined by Steve Marriott, it was Frampton who formed Humble Pie. The two singer/guitarists had become soul mates and jamming buddies in the disillusioned months after the Herd. Steve understood. His group, the Small Faces, had gotten caught in the same teen tread mill. When Peter started forming a new band with drummer Jerry Shirley, it took less than a month for Marriott to decide he wanted in. Bringing with him ex-Spooky Tooth bassist Greg Ridley, the quartet was solidified. “It was incredible in the beginning,” Peter remembers. “Even though Steve and I were completely different in our approaches, we were really out to beat the game together. Here we were – ultraserious musicians – and both of our bands had turned into pop outfits. We all grew beards to hid our faces. All we wanted was to make it on our own terms.”

The first two Humble Pie albums suffered for exactly that reason. Giddy with their newly acquired freedom, the band wanted to do it all – rhythm & blues, folk, jazz, ballads, rock & roll. Town and Country and As Safe as Yesterday Is sold reasonably well, but in the end it became obvious that the audiences wanted only rock & roll. The more free-form elements of Pie’s stage show were hooted.

Humble Pie and Rock On, the group’s first two records for an American label, firmly established that Humble Pie had gone heavy metal, a fact that had already became obvious on their unending concert trail. A live album was recorded during a two-day stint at the Fillmore East. The minute Frampton heard the tapes, he knew The Pie would be huge. He wanted no part.

“Once again,” Peter explains, “the audience had chosen our direction. The heavy stuff . . . that always went down the best, so there we were, doing it all the time. And there was no turning back. We would have to remain that way for the remainder of the band. I was the only one in the group who really didn’t want to do that heavy riffing all the time. I don’t write those types of songs.

“So I figured I’d leave then, before the album came out. It would give them a chance to get somebody else who would be readily accepted. I mean, if there ever was a best time for leaving, that was it. So I did.”

The other members of Humble Pie found Frampton’s decision mystifying, of course, but there was little bitterness. Dave “Clem” Clempson quietly took his place and Rockin’ the Fillmore shot Humble Pie into the big leagues.

Dee Anthony, Humble Pie’s manager, retained Frampton as a client even though the artist had no immediate career plans. Peter watched his former band skyrockert while working diligently as a sessionman on George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass, Harry Nilsson’s Son of Schmilsson, John Entwistle’s Whistle Rhymes and a number of advertisement jingles.

Frampton recalls being extremely content and relaxed, taking his time about wandering back into the limelight. Fellow sessionmen volunteered their invaluable services should he choose to make a solo album. Finally, in ’72, he booked studio time and started work on his first album, Wind of Change. To Peter’s surprise, sessionmen like Billy Preston, Klaus Voorman, Nicky Hopkins, Jim Price, Bobby Keyes and Ringo Starr flocked around. It was an especially fruitful time for Frampton. Songs like “All I Want to Be (Is by Your Side)” and It’s a Plain Shame” were written and recorded in a number of hours.

The album was well received but sold modestly (particularly in comparison to Humble Pie’s Smokin’, which had been released shortly beforehand). But after a flurry it plummeted to oblivion, leaving Frampton to map out a new strategy. It didn’t take long for him to find it. “I knew I wasn’t going to sell any records sitting at home, so . . . I took to the road.” In three days, his first tour to break into the black would open in Orlando, Florida. All the roadwork, he says, has simply managed to pay for itself. But, in fact, he’s often had to borrow money to continue his career.

“It got to the point where I couldn’t afford to borrow any more money to lose. Know what I mean? That was just before Frampton, my fourth album. As we were recording it, I was very down and depressed. At the time, the thought of a tour was a puzzle. I didn’t really want to get into any more debt. But I did. And it worked.”

Originally, it had been Peter’s third album, Somethin’s Happening, that was groomed for mass appeal. The title track would catapult him to his present status. “This is my plum,” he told an interviewer at the time. “If anything does it for me, it’s this song.”

The single bombed. Miserably. The album slunk off the charts. “Looking back, I can see the weaknesses, but watching that album fizzle out and disappear was so painful. That was the most disheartening of anything. That was the point where it was almost back to being a sessionman. I definitely thought about it.” He adds the afterthought: “Heavily.

Whatever the reason, Frampton came closest to fully capturing the artist on record. The album fell just short of gold, and a single (“Money”) did well. Frampton began headlining more regularly, playing for audiences that were more familiar with his songs.

Sensing the momentum, Frampton decided to play his trump – the live album.

“I knew it was the right thing to do,” he boasts. “I was the one in Humble Pie who wanted to do a live record. I wasn’t the only one but I was certainly the one who felt it the most. I could feel the same sort of confidence in my own career when I said, ‘Dee, let’s do it. The next one’s got to be live.’ But it was a long time between the two.”

Frampton Comes Alive! was originally meant to be another single album. “I was told to keep it to a one-record package,” Frampton recalls, “‘cause the day of the double live album is gone. I agreed, you know. So I mixed and cut together the whole thing, with ‘Lines on my Face’ and ‘Do You Feel’ on one side and ‘All I Want to Be,’ ‘Something’s Happening,’ ‘It’s a Plain Shame’ and ‘Jumping Jack Flash’ on the other. That’s all.

“Then Jerry Moss [president of A&M Records] came into the studio and there was this great moment when, after I’d finished playing the single album, everybody looked at me and said, ‘Can we hear the other album?’” Frampton laughs. “Just another great moment in rock & roll,” he snickers. “I felt very small because . . . ‘double album?’ But, but, . . . I thought . . . I thought that you . . . one double album, coming right up. I’m happy it’s a double, obviously. I like the stuff that I didn’t think we would get to use – ‘Money’ and all the acoustic ones.

“And Jesus, I sure didn’t think I’d get such a big ‘yes, we like you’ out of the whole project.

“I enjoy playing onstage more than anything,” says Peter backstage. “It doesn’t really matter to me that I’ve probably played ever place with a stage in this country. I’ve seen a lot of tiny holes . . .”

The Orlando Sports Arena, it would be safe to say, is one of the larger holes Frampton has headlines. Tonight, the golden combination is pot and beer, as 12,000 stoned Floridians have gathered here at this glorified airplane hangar to see the first show of Peter Frampton’s current tour. Dee Anthony is here, too, having flown in just to lend support on the eve of his newest superstar’s biggest season yet.

After Gary Wright, another Anthony act, has warmed up the crowd with a set built around his current hit, “Dream Weaver,” Frampton wanders out onstage to tumultuous applause. There is a collective sigh from the many young girls in the audience. Peter looks great, still well tanned from his vacation and wearing tight green velvet pants with a white, unbuttoned shirt. “I’m not that self-conscious anymore about the way I look,” he had confided earlier, “I figure, fuck it, why deny yourself . . . “

Hit with a single spotlight, Frampton receives an acoustic guitar, seats himself on a stool at center stage and begins strumming the opening chords to “All I Want to Be (Is by Your Side).” After the applause dies down, the audience becomes as quiet as a sold-out party crowd can get. They remain miraculously respectful, booming their approval only at the end of each of several soft songs like “Do It Again One More Time,” “Penny for Your Thoughts” and “Baby, I Love Your Way.” Frampton cuts a sincere figure onstage. Fresh and vibrant in voice and action, he appears to mean it. Which makes an audience like this one feel wanted.

Even though he has always performed an extremely melodic solo act, he has only recently added the acoustic numbers to his stage show. Dee Anthony figures this is one of the big factors in Frampton’s breakthrough. “Peter has played on the bill with a lot of heavy-metal acts. They waste an audience down, physically wear them down. What is a beautiful, lovely little guy like Peter Frampton going to do when he comes out? Is he going to try to go over their energy level, saying, ‘I’m going to rock right over them?’ Of course he can’t. So we just reversed the process and started him wide open, from nothing, just acoustic guitar. And he builds. He goes in like a lamb and out like a lion.”

When Frampton straps on his black Les Paul, there is genuine hysteria. “Something’s Happening,” his first electric song of the evening, has everybody shouting the words. They roar like a football crowd.

I know it’s my year

Ain’t got no fears . . .

There was a time, several years back, when Peter flirted with the moody pose of ever other English guitar star. Now he works the stage with the assurance of a master showman, bouncing and waving to every part of the crowd. He talks with them between numbers in a youthful, high-pitched sort of yelp, jives with the shouted requests, gets the house clapping with little effort and acts like he belongs there. “I’m not so embarrassed of the things that I say onstage as I was when I first started,” he later explains. “It’s just a matter of having the confidence to do that, which I never thought I’d get. But because the people started picking up on the music so much. I began to geel everything much more. That’s the whole story, really.”

Maybe not the whole story. The fact is that Frampton has benefited from the long hours he’s spent studying Django Reinhardt, among other guitarists. His style has sharpened and matured considerably since the early days of Humble Pie.

Grinning, Peter works his way through the meat of his set. The responses get louder with every song: “Lines on My Face,” “Show Me the Way,” “Money,” “It’s a Plain Shame” and the synthesizer-bagged tour de force “Do You Feel like We Do” – Frampton has honed these numbers into perfect stage vehicles. His solos are short and curt, the musicianship blazing.

The band – Bob May on keyboards and guitar, Stanley Sheldon on bass and John Siomos on drums – couldn’t be better. Frampton has never had a more versatile backing group. They bring to the lighter material a sophistication and to the more electric numbers a backbone. The encores, “White Sugar” and “Jumping Jack Flash,” bring the crowed to a frenzy, the entire tin venue teetering on the verge of collapse.

His face buried in a towel after the show, Frampton still can’t quite believe it all. “I know I keep going on about it,” he apologizes, “but isn’t it amazing how things can change with one album? Even a couple of months ago it was nowhere near this. Now . . . “

He is interrupted by a teenage fendor, a sneak-in from backstage. “Hey Peter, you were great. Keep it up, buddy.”

This is interesting. There is no fawning fan-to-demigod interaction. The vendor clasps Frampton’s limp playing hand for a hearty handshake. “Lemme tell ya. You really got it together for 25. All right. You got it.” It’s as if Frampton had just batted in a few runs. “Twenty-five. All right . . . “

“Almost 26,” Peter offers. “Over a quarter of a century, you know.”

“I know, pal.” The vendor slaps a hand on Frampton’s bare, sweaty back. Frampton is too stage-numb to feel it. “How long you on tour for?”

“Ever,” Peter replies without even thinking. But he quickly brightens. “I’ve got May and June off, though. Two months.”

“Outasite. You’re doing all this and you’re only 25?”

Peter nods.

“All right.” The vendor shakes his head and slips out the dressing room door. Once outside, his girlfriend has a million questions. “Did you talk to him? What’s he like?”

“Like us, if we were rock stars.” The vendor pauses. “Wendy? What the fuck am I doing selling Pepsi?”

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #211 – Cameron Crowe – April 22, 1976