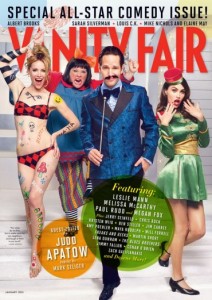

Rockin’ The Role – Extended Vanity Fair Story

Here’s an exclusive treat. This is the extended version of the story that ran back in the January, 2013 issue of Vanity Fair. It’s nearly 1000 words longer and digs a bit deeper into the subject. We hope you like it.

When Musicians Act – And It’s Not Terrible

So many musicians have been drawn in by the allure of the silver screen only to get burned. But when the moonlighting succeeds—think Whitney Houston, Art Garfunkel, Courtney Love, Eminem—the result can be riveting.

There is a wonderful moment in Judd Apatow’s Funny People that is as surprising as it is funny. Seth Rogen portrays a struggling young writer-comic invited along on a corporate gig to assist his idol, a legendary stand-up comedian played by Adam Sandler. James Taylor is also on the bill, and in a casual moment after Taylor’s performance, Rogen asks him “Do you ever get tired of singing the same songs over and over?’” Taylor, playing off a long career based on graceful elegance, sharply replies, “Do you ever get tired of talking about your dick?”

For anybody paying attention to the long and tumultuous history of musicians crossing over into the dark and mysterious world of acting for film, this was a watershed moment. Taylor was operating far out of his comfort zone, throwing in with Apatow’s famously unruly gang of screen-comedians. He nailed his moment with aplomb. This doesn’t happen often. The cinematic battlefield is littered with the bodies of musicians who have not fared as well. Though musicians and actors often long for each other’s careers, crossing over is the Holy Grail. The results are often calamitous, and rarely less than riveting.

To discuss this thorny issue of acting musicians, I went to James Taylor himself. Taylor has had a front-row seat to this time-honored challenge. In the early months after Taylor’s momentous 1970 success with Sweet Baby James, he was one of the first approached to portray Harold in Harold and Maude. (He declined, as did Elton John, before director Hal Ashby settled on the quintessential Harold, non-musician Bud Cort.) Taylor did say yes, however, to an even more unorthodox project, written by Rudy Wurlitzer, and directed by Monte Hellman. The road movie was called Two-Lane Blacktop, and though it enjoys success to this day as a serious time-capsule piece of 70’s auteurism, the filming was torturous for Taylor. (The movie also starred Laurie Bird, Warren Oates, and another musician new to acting, Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys.)

“We only got a page of the script at a time,” recalls Taylor from his Connecticut home. The frustration still sounds fresh. For months, he watched the valuable time of his post-Sweet Baby James success tick away while attempting to maneuver the movie’s stringent existentialism. Was he given acting advice? “Quite the opposite. We were told to drain our faces of emotions, and not to ‘act’ at all.” Taylor happily returned to music. When he was approached the next year to star in the remake of A Star Is Born, in a part written specifically for him, he passed. (The project then went to none other than Elvis Presley, who nearly agreed, before the part ultimately landed with Kris Kristofferson).

It’s no surprise to Taylor that many actors dream of a side-line career in music. But, he warns, “there’s much more control in music. Music, as an art form, is almost like a human language… but where languages are made up of symbols representative of other things, music is the thing itself. It’s a physical reality. It cuts across all cultures and all creatures. A dominant chord with a 7th in it, for example, wants to resolve to the one chord and the tension of wanting to go someplace, and then going there, or not going there… it produces an emotional effect. It’s straight to the heart. There’s no argument to it. It’s a matter of physics. (A musician who acts) finds himself dealing with many more intangibles.”

Or, in the words of Graham Parker, who plays himself in a sharp and funny appearance in This is 40: “Pop musicians are too full of themselves to act properly. It’s all preening and posing for us. We mug, we mime, we throw shapes, we pose, we do weird things with our eyeballs, but we can’t act. I think deep down many musicians, myself included, consider acting and film making a much higher art form and we wish we were actors. We spent too many time in music trying to manipulate people’s emotions in under ten seconds. It’s excessively phony. I don’t know why there aren’t more actors whose music is any good, though. But let’s leave Jeff Bridges out of this. He’s allowed to do anything and it’s always good.”

Indeed, acting for film requires a different discipline, working generously with fellow actors, a script-supervisor, a cameraman, specific lighting, and ultimately surrendering the quality-control to a director and editor….in other words, none of the rebellious independence that makes for an epic rock star. Still, there are wonderful bravura moments where musicians have conquered the silver-screen. Courtney Love in The People Vs. Larry Flynt. David Bowie in Basquiat, The Prestige, The Hunger… or anything. Whitney Houston in The Bodyguard was surprisingly free, infused with humor and emotion and attitude. Glen Hansard and Markéta Irglová were so authentic as a budding duo in Once, they fell in love.

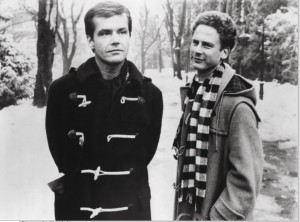

- ALREADY FAMOUS Jack Nicholson and singer Art Garfunkel in 1971’s Carnal Knowledge.

There are some obscure favorites as well. The Guess Who’s Burton Cummings took a lead role in the 70’s feature Melanie. His bravura piano-serenade in the nude makes the entire movie an instant classic. (“I’m in the nude, for loooove.”) Art Garfunkel was achingly good in Carnal Knowledge. Marvin Gaye and John Lennon both showed promise in early attempts at acting. Madonna made it look easy in Desperately Seeking Susan. Steven Van Zandt crushed in The Sopranos. Bob Dylan is always surprising on screen, particularly in Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy The Kid. Ironically, he’s far more relaxed at capturing his famously elliptical rhythms on screen then the host of A-list actors employed to portray him in I’m Not There. Mick Jagger started out powerfully in Performance, moonlit infrequently after that, and then surfaced recently as a remarkable comic actor in his 2012 hosting-and-performing turn on SNL.

Producer Lorne Michaels certainly knew the stakes involved. A long-time personal friend of Jagger’s, he’d known for some time that the singer had the humor and the fearlessness to do it. Still, reinventing the world’s most famous lead-vocalist as an SNL host was no small endeavor.

“The key,” says Michaels, “is rhythm and timing.” He adds, “You have to know how they can be funny, because it has to be an extension of who they are.” His track record is solid – he’s helped guide Justin Timberlake and Bruno Mars into the same winner’s circle. Michaels’ love of tailoring the comedy to the musician began with the second show of SNL, when he paired Paul Simon with basketball great Connie Hawkins. The height difference was instantly funny. Later he dressed the often-solemn Simon in a large turkey costume. It worked. But Jagger was the trickiest of all. He explains: “Mick is a pure performer. He can’t be buffoonish. He can be silly, but he has to find a way in, so that he can still be Mick and do a character.”

There was also the audience to consider. “It wasn’t like a Rolling Stones show, where you know he’s going to do three songs, kill, and then he’s going to talk. They’ve already won by the time they open their mouths. In comedy, you’re coming out (to a monologue), there’s applause, then you have to win. We needed an opening line, you know that line that settles everyone? I think it was John Mulaney or Seth (Myers) who found it just before dress (rehearsal). And it was Mick’s line – ‘I’m here because I get to do what I do best, standing still and talking.’” Michaels laughs appreciatively. “The audience just went, ‘right, we’re with you.’ It’s that first moment when you make contact, it’s everything.” The wrap party was euphoric, with Jagger joyously knocking out versions of “Miss You” and “Bitch” with Foo Fighters on the Rockefeller Center skating rink, playing long into the night for shocked passersby. “It only took 37 years to pull off,” notes Michaels.

To quote another Rolling Stones song, it’s not easy.

One major problem in musicians learning to drop all the pretense of their usual job is the thundering voices of their potentially-caustic peers. I had fun directing Pearl Jam as struggling rockers in Singles, though Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Anthony Keidis apparently chastised at least one member for an entire Lollapalooza tour. (Turnabout would happen quickly. Keidis’ cameo in Point Break evened the playing field.) Jerry Cantrell, from Alice in Chains appeared in Jerry Maguire, playing an all-night Copymat clerk, and possibly a Messiah, who helps Maguire design his Mission Statement. Cantrell was fearless. He nailed the performance in two takes, earning a blitz of high-fives from co-star Tom Cruise. Sometimes the reckless naturalism of a relaxed musician is just what the scene needs, like Mark Kozelek in Almost Famous and Vanilla Sky. He is a lucky charm, and my go-to guy for dark rejoinders like “Dude – fix your fucking face!” (Mark fares well in Shopgirl too, along with the actor-drummer Jason Schwartzman.)

Another fear for the wannabe musician-actor is the chance of losing rock mystique. “I have no image,” Graham Parker happily notes, “therefore I don’t give a shit.” Others do. When Bruce Springsteen first arrived as a major force in the mid-seventies, his charisma was so large, so cinematic, it was widely assumed he was built for the big-screen. Springsteen knew better. After fielding a blitz of offers, he decided “The Character” lived most vividly on records and on stage. Springsteen has held himself almost entirely off-screen, outside of a few videos and a brief appearance as himself in High Fidelity. And James Taylor, after Two-Lane Blacktop, long kept his own acting jobs to a memorable appearance on The Simpsons, and a nice turn with Barbara Hershey in the 1997 video for his song “Enough To Be On Your Way.” (Until, of course, Apatow called with Funny People, and a game-changing dick joke.)

“I consider acting something I like to do,” says Taylor. “But mostly my career is a matter of touring and recording, and sometimes you participate in the other stuff to keep yourself in the public eye. Some artists, like Joni Mitchell and Miles Davis, are already such vivid personalities, such trail-blazers, I can’t even imagine them acting. It would take time away from the importance of who they are.” He pauses. “Speaking of Joni Mitchell, there is a wonderful cover of her song “River,” by Robert Downey, Jr. So there’s an example of an actor with a musical soul. Being a musician is actually not that far from being a music fan.”

He brings up a good point. Sometimes an actor’s own love of music infuses them with the ability to play a musician credibly. Gary Oldman’s Sid Vicious is an example. Tom Cruise scores in Rock of Ages, in no small part because he’s a Guns ‘n Roses fan and took the time to study Axl Rose… and his posture. Reese Witherspoon and Joaquin Phoenix led with their musical hearts in Walk The Line. Same with Bill Nighy, who is allegedly the world’s biggest Rolling Stones fan, complete with a home stocked with every bootleg. He waltzed into one of the best portrayals of a burned-out sixties pop icon ever in Love Actually.

For Almost Famous, as well as David Chase’s beautifully poetic 60’s music piece, Not Fade Away, the actors had a rock boot camp before filming. Chase’s movie band, The Twylyght Zones, and our band, Stillwater, both benefited from late-night rehearsal sessions where we gorged on the greats and near-greats, read up, watched everything, and conducted long-hours of music lessons. Under the training of Peter Frampton, himself a sometime actor, Jason Lee was able to stand and deliver his lead-vocals with authenticity, and Billy Crudup learned lead-guitar in a scant six weeks. Every once in a while, he still calls me up and leaves a damn good version of “Smoke on the Water” on my voice-mail.

But the King of the Rock Fan Actor is indisputably one man – Jack Nicholson. While Nicholson has only rarely played a musician (Stoney Jackson in Psych-Out ), he understands music as few do. I once sat one seat away from Nicholson at a Neil Young and Crazy Horse show. He wore his trademark dark-sunglasses and nodded his head deeply, as if it were ‘66 and this was Coltrane at the Village Vanguard. I snuck a look over at him, and grabbed a glimpse of his eyes through the sides of his glasses. They were shut, lost in reverie. Yes, I too wondered if he was asleep, but those fears were quickly banished when he leapt to his feet as the last chord of “Cortez The Killer” was played. This man loves his music.

And then there’s Elvis Presley, who is worthy of any rainy-day trip through his catalog of 31 movies (and two documentaries). The King began his career with dreams of crossing over as a kind of Marlon Brando/James Dean. He was well on his way early on, before getting derailed into a long string of vehicles like Roustabout and Girls, Girls, Girls. But Elvis is never less than fascinating, even when he was banging out three movies a year and barely keeping track of which girl, animal, car, co-star or guitar he was performing with. A performer either has built-in screen presence or he doesn’t. Most don’t. Elvis did, every time he stepped in front of that big glowing camera.

Which brings us back to James Taylor and his epic turn in Funny People. Taylor arrived on the set and was surprised to find that Apatow’s film was a long way from Two-Lane Blacktop. Taylor was now in the company of Rogen, Sandler and a host of other collaborative comedians. Suddenly there were lines being shouted from behind the camera, and no one paid much attention to the words “action” or “cut.” There was only one line he questioned – “Fuck Facebook.” But after trying the line as “Screw Facebook” a few times… the lure of the set overcame him, and Taylor whipped out a “Fuck Facebook.” The crew and actors erupted in laughter and applause. Touchdown. It’s the take in the movie. “They were right,” Taylor agrees, ever the student of the form. “’Fuck Facebook’ is an alliteration, which makes it funnier. That’s acting. You surrender your self-consciousness for the greater good…“

That Judd Apatow has enjoyed directing success with James Taylor, as well as other musicians like Eminem (Funny People, 8 Mile), Loudon Wainwright III (Knocked Up, Elizabethtown), and a poignant Graham Parker (This is 40) is no accident. He enjoys bantering with the artists, relaxing them with new jokes and new approaches, and generally gives them the greatest busman’s holiday ever from the business of music. But alas, it is a lonely job. After Eminem nailed his own watershed moment in Funny People – sexually taunting Ray Romano from across a crowded restaurant – there was a similar roar of approval from the crew. Eminem then promptly left to celebrate, grabbing only Adam Sandler and retiring to his car to listen to his own newly finished album. Apatow watched the thumping car, uninvited, and was left to bask in yet another rare acting-musician victory…. alone.

“I enjoy working with musicians, love the energy and the creativity.” Apatow sighs happily. “I get to be their best friend… for an hour.”

Courtesy of Vanity Fair – Cameron Crowe – January, 2013